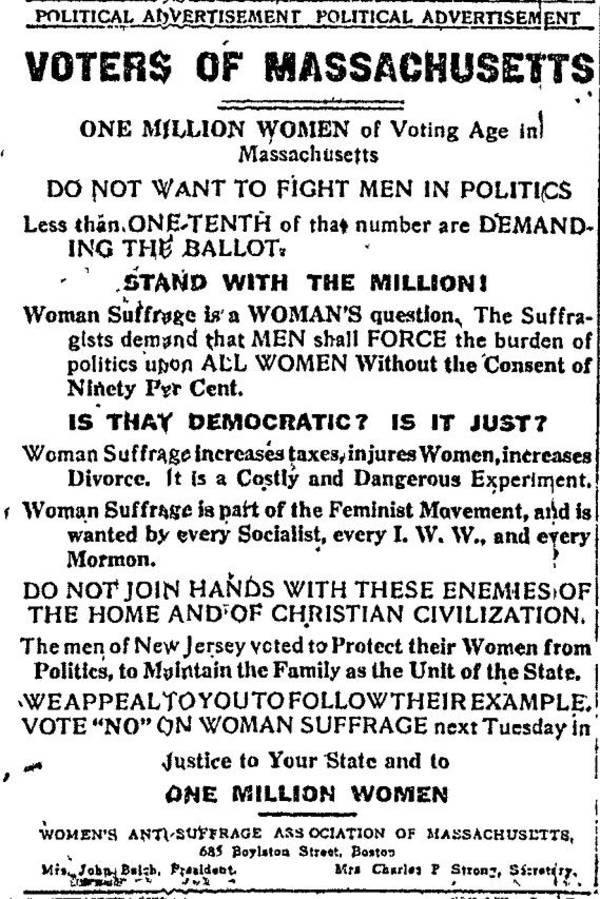

The vintage clipping below is a political advertisement from 1915 opposing women’s suffrage in Massachusetts. It claims that most women in the state do not want the vote, so if voting men gave women suffrage, they would be doing so against their will. This, they claim, would be undemocratic. This sounds ironic, but it makes sense in a world where men were suppose to be women’s political representatives.

The ad then goes on to try to demonize those women who do want the right to vote by associating them with other groups widely stigmatized at that time: feminists, of course, but also socialists, Mormons, and members of the I.W.W. The acronym stands for Industrial Workers of the World, an organization founded in 1905 as an alternative to the American Federation of Labor, reportedly consisting of anarchists, socialists, and union members (wiki).

Women in Massachusetts would be granted the right to vote on this day, August 18th, five years later, not by the residents of the state, but by Federal decree.

Via BoingBoing.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.