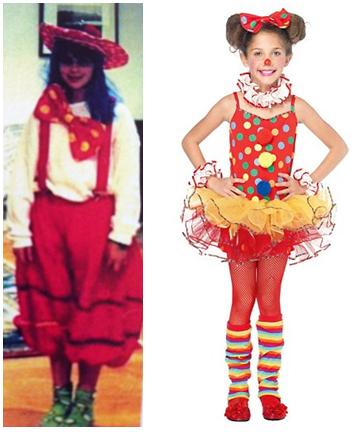

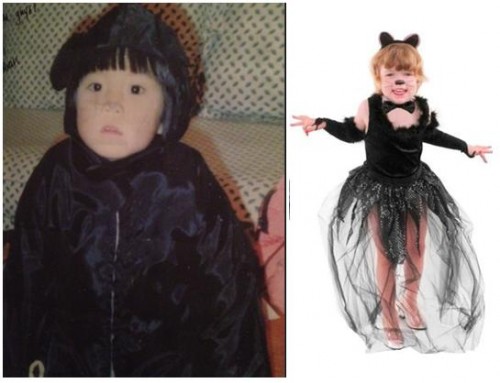

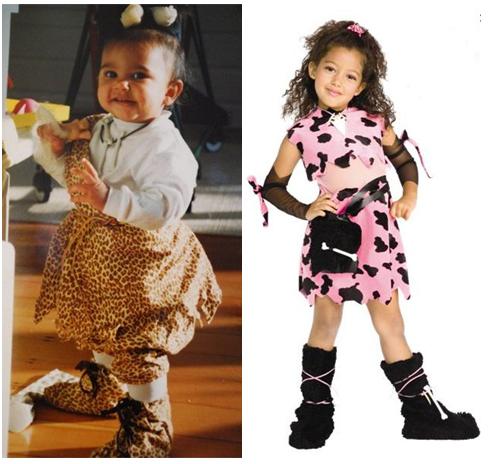

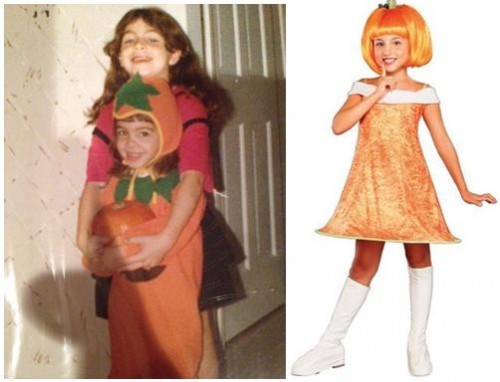

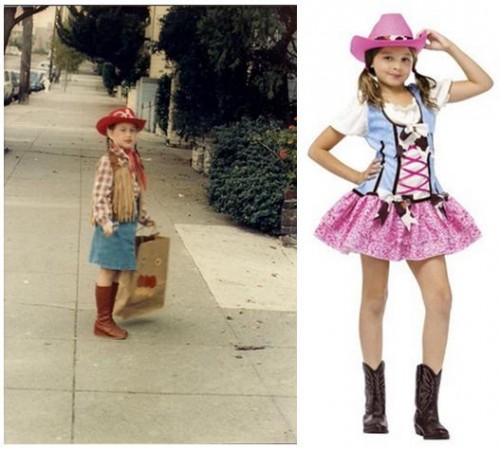

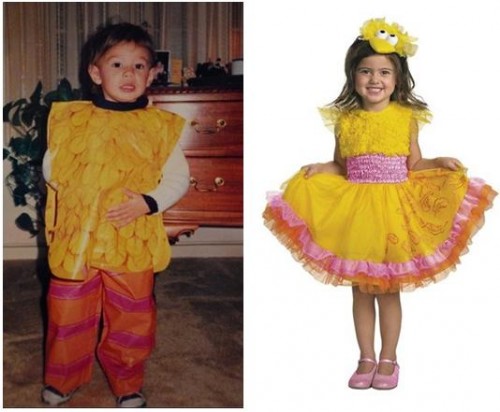

It’s become a tradition, every year about this time, to have a national conversation about the rise of sexy Halloween costumes, especially for little girls. But are they really sexier than before?

Sure enough. Jessica Samakow at the Huffington Post put together a gallery of then and now photos, sent along by Katrin. See for yourself:

More about sexy costumes for women and girls: boy and girl cookie monster costumes, when sexy overtakes all reason, sexy femininity and gender inequality, sexy scholar, Harem girl, the sexy body bag costume, and a Halloween gender binary.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.