Ray Rice’s violent assault of Janay Palmer has placed a spotlight on the criminal records of professional football players more generally. It is tempting to presume that men who spend their lives perfecting the use of violence are more violent in their day-to-day lives, but we don’t have to speculate. We have some data.

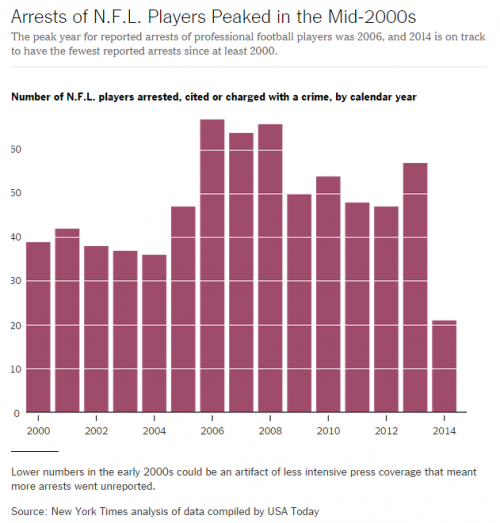

USA Today maintains a database of charges, citations, and arrests of NFL players since 2000 (ones they found out about, in any case). According to their records, 2.53% of players are arrested in any given year. This is lower than the national average for men of the same age. And, despite the publicity, this year looks like it will be the least criminal on record.

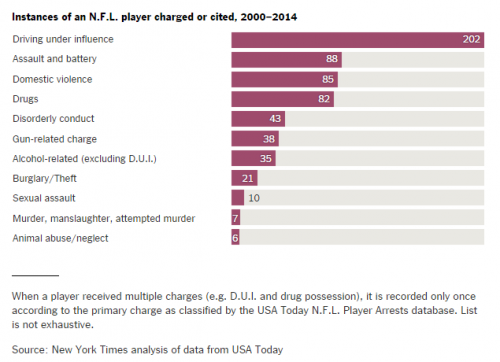

Domestic violence is the third most common charge or cite, following closely behind another violent crime, assault and battery. But by far the most common trouble NFL players face is being charged with a DUI.

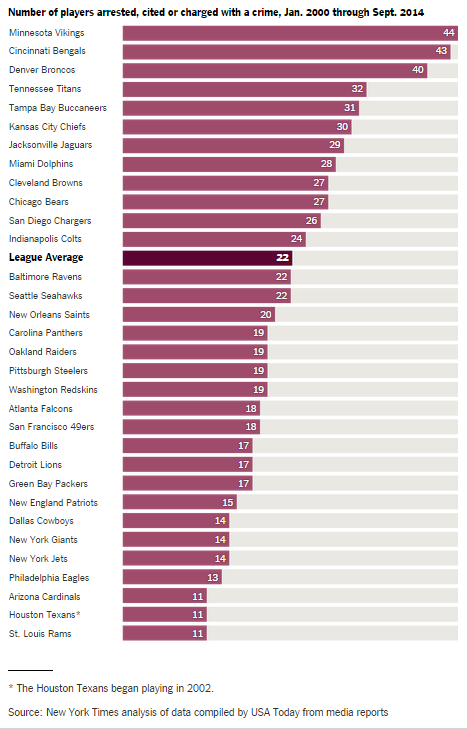

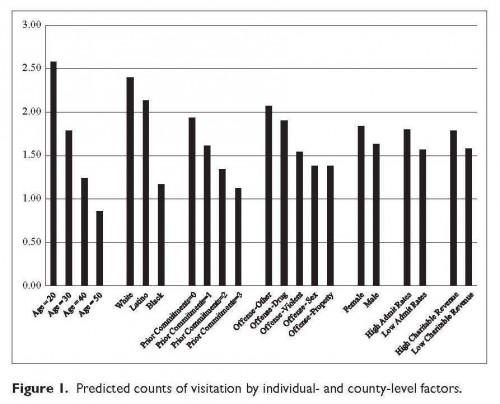

Interestingly, not all teams have similar rates of arrests, charges, or cites. These data below reflect 15 years of data, showing the wide disparity among teams. The number of run-ins with police tend to correlate well year-to-year, so this chart represents a stable trend.

Neil Irwin, writing at the New York Times, says that varying levels of criminal activity may be related to club culture (that is, some franchise’s may be better at suppressing or inciting criminal activity than others) or it may be influenced by the cities they play for (e.g., there won’t be as many DUIs in cities like New York City where there’s substantially less driving). Both are great sociological explanations for the variation between teams and consistency across seasons.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.