Flashback Friday.

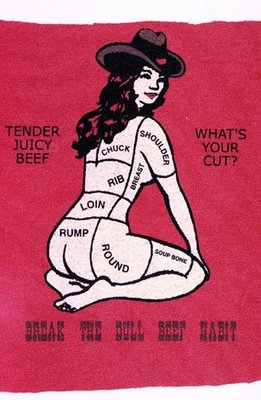

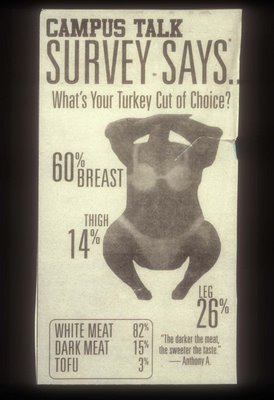

In her now-classic books The Sexual Politics of Meat and The Pornography of Meat, Carol Adams analyzes similarities in the presentation of meat products (or the animals they come from) and women’s bodies.

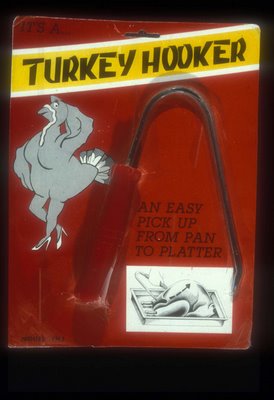

She particularly draws attention to sexualized fragmentation — the presentation of body parts of animals in ways similar to sexualized poses of women — and what she terms “anthropornography,” or connecting the eating of animals to the sex industry. For an example of anthropornography, Adams presents this “turkey hooker” cooking utensil:

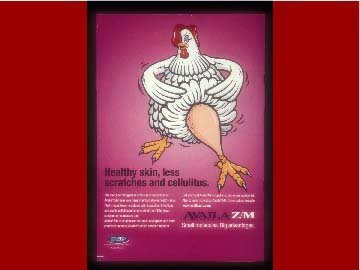

Adams also discusses the conflation of meat/animals and women–while women are often treated as “pieces of meat,” meat products are often posed in sexualized ways or in clothing associated with women. The next eleven images come from Adams’s website:

For a more in-depth, theoretical discussion of the connections between patriarchy, gender inequality, and literal consumption of meat and symbolic consumption of women, we highly encourage you to check out Adams’s website.

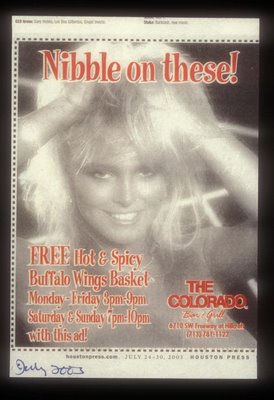

This type of imagery has by no means disappeared, so we’ve amassed quite a collection of our own here at Sociological Images.

Blanca pointed us to Skinny Cow ice cream, which uses this sexualized image of a cow (who also has a measuring tape around her waist to emphasize that she’s skinny):

For reasons I cannot comprehend, there are Skinny Cow scrapbooking events.

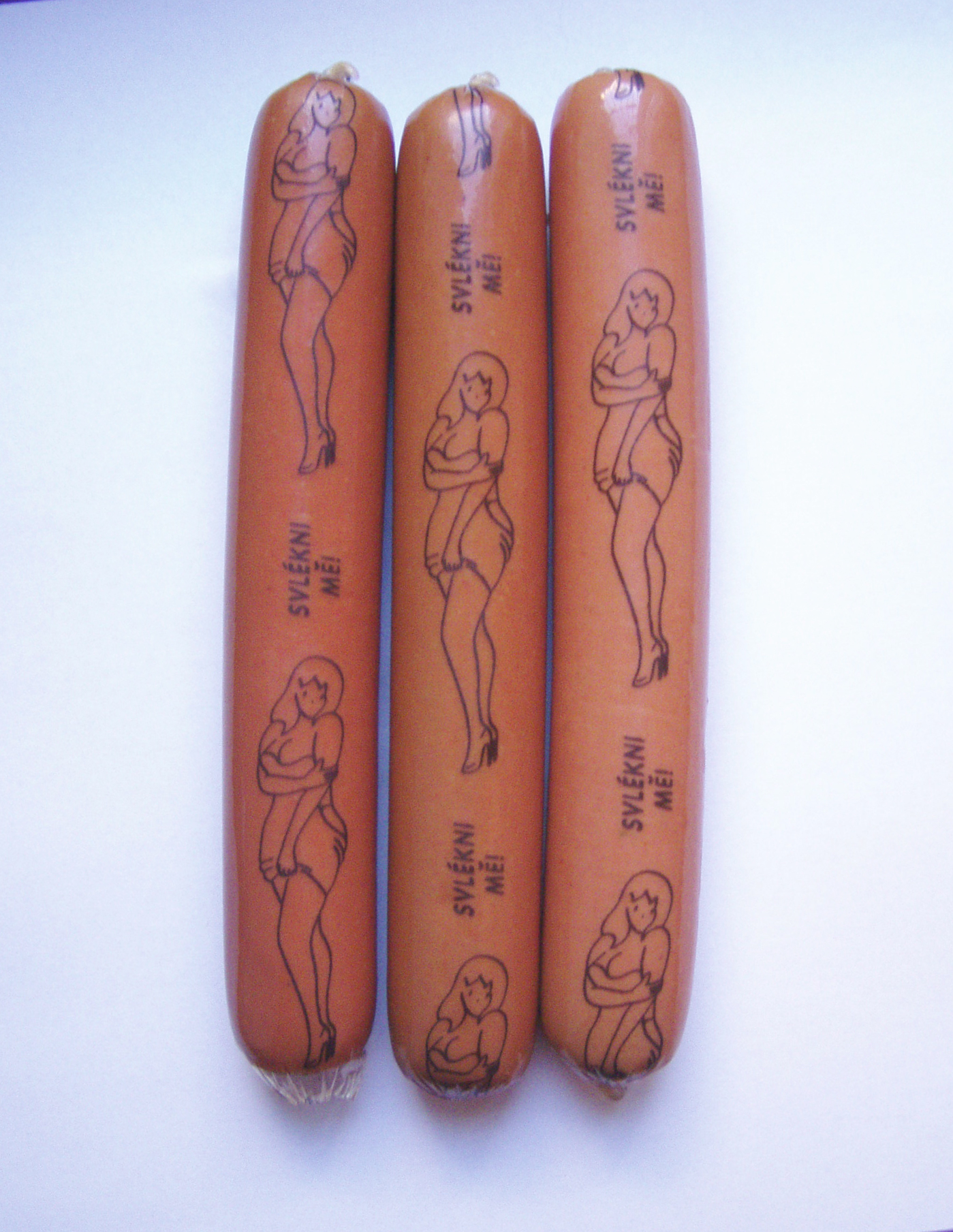

Denia sent in this image of “Frankfurters” with sexy ladies on them. The text says “Undress me!” in Czech.

Finally, Teresa C. of Moment of Choice brought our attention to Lavazza coffee company’s 2009 calendar, shot by Annie Liebowitz (originally found in the Telegraph).

Spanish-language ads for Doritos (here, via Copyranter):

Amanda C. sent in this sign seen at Taste of Chicago:

Dmitiriy T.M. sent us this perplexing Hardee’s French Dip “commercial.” It’s basically three minutes of models pretending like dressing up as French maids for Hardees and pouting at the camera while holding a sandwich is a good gig:

Dmitriy also sent us this photo of Sweet Taters in New Orleans:

Jacqueline R. sent in this commercial for Birds Eye salmon fish sticks:

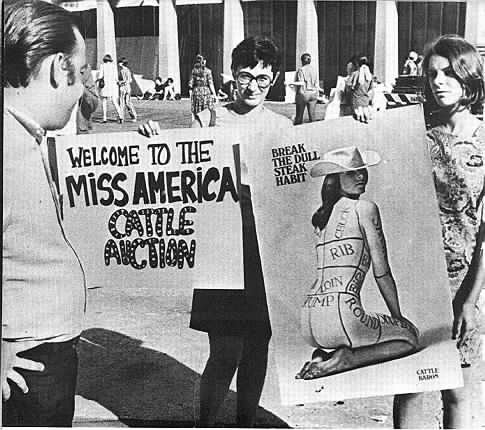

Crystal J. pointed out that a Vegas restaurant is using these images from the 1968 No More Miss America protest in advertisements currently running in the UNLV campus newspaper, the Rebel Yell. Here’s a photo from the protest:

Edward S. drew our attention to this doozy:

Dmitriy T.M. sent us this example from Louisiana:

Haven’t had enough? See this post, this post, and this post, too.

Originally posted in 2008.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.