At Everyday Sociology, sociologist Karen Sternheimer made a nice observation about the problem of teen drinking. It’s not our biggest alcohol problem.

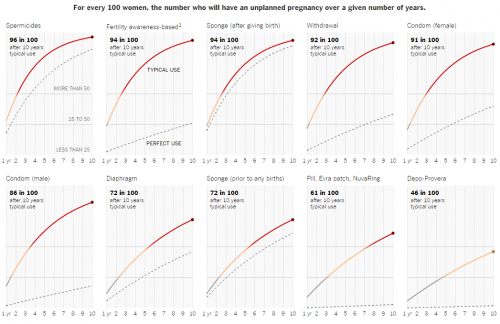

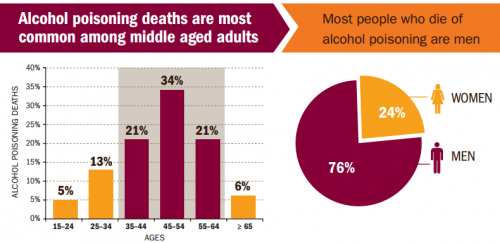

According to the CDC, the age group most likely to die from binge drinking is people 35-64 years old. In fact, three out of every four alcohol poisoning deaths are in this age group — 4.5 out of a total of 6 a day — and 76% of them are men, especially ones who earn over $70,000 a year.

So why all the PSAs aimed at teens?

Sternheimer argues that the focus on teens has to do with who what groups are identified as problematic populations. In the 1800s and early 1900s, she points out, laws were passed in several states making it illegal for African Americans and Native Americans to drink alcohol. Immigrants were also targeted.

Young people weren’t targeted until the student rebellions of the 1960s and ’70s. Like the “protest psychosis” attributed to black Civil Rights activists, the anti-establishment activism of young people was partly blamed on drug and alcohol use.

Today, she observes, the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism focuses its attention on young people, minorities, women, and people with HIV.

It’s about power. She writes:

White, middle-class men over thirty typically have more social power than the groups commonly targeted as problems. They also vote, and no sane politician is going to campaign warning of the danger some of these men cause and how we can control them.

Not to mention, she says, how the alcohol industry would feel about the government telling their richest customers to curb their drinking. They much prefer that PSAs focus on young people. “This industry can well afford the much-touted ‘We Card’ programs,” says Sternheimer, “because teens usually don’t have the money for the expensive stuff that their parents can buy.”

The industry’s marketing to wealthy, white men, then, goes unchecked.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.