Some ecards via Feministe.

Some ecards via Feministe.

Another example of hair removal and standards of female beauty. Not at all subtle encouragement for women in the new ad from Schick/Wilkinson Sword razors for women. Shaving apparently makes you happy enough to sing songs with obvious innuendo.

[youtube]https://youtu.be/rfed1DT1PGA[/youtube]

SocProf, from The Global Sociology Blog, has an interesting post about gender in the public sphere. Here is a photo (from Echidne of the Snakes) of the “first spouses” of the G20 nations (that is, the spouses of the political leaders of the G20):

Except…someone’s missing. Two of the G20 countries (Germany and Argentina) have heterosexual, married female leaders, and their husbands aren’t in the photo. I don’t know why–were they not invited to the event? Did they choose not to come? SocProf asks, “Would the husbands have looked out of place here? Would this have been embarrassing to them?”

But SocProf points out that a different disappearing act recently occurred in Israel:

…look what happened in reverse in a group photo of the newly-formed Israeli cabinet. On top is the traditional cabinet group photo, at the bottom is the “touched-up” version that appeared in [the ultra-Orthodox newspaper Yated Neeman]… notice the difference?

Indeed, the two female Cabinet members have been photoshopped out.

SocProf says,

[In the G20 photo]…the men are not visibly absent. It is their presence that would be noticeable. And also note the setting in which the women pose, the soft colors, pink carpet and sofa with pastel background. It looks like a somewhat formal yet a little domestic setting.

The bottom photo is formal, no pink or pastel there! Icy grey with flags and orderly pose…It is a perfect illustration of the gendered domains: where men belong and where women belong.

Taken together, the three images, though taken for different purposes in different places, provide a great illustration of how we often make people who don’t fit cultural gender norms invisible…sometimes very literally.

Also see our post on an ultra-Orthodox newspaper that airbrushed girls out of a photo of children.

UPDATE: Commenter Liz says,

I object to the use of the word ‘airbrushing’, because that’s not what happened: those photos were edited, manipulated, or fabricated, but airbrushing is a specific photoshop tool for minor modification. You can’t completely change the reality of a photograph with an airbrush, unless someone would like to tell me that those two male stand-ins are actually just drawings made with photoshop.

If you use the same word (airbrushing) for taking out a model’s cellulite as well as removing heads of state from photographs, you trivialise what’s been done. Digital editing is only going to become more and more common, and it’s important to find the right words to explain how a photo has been altered.

Good point–thanks for pointing the language issue out. I didn’t know what airbrushing referred to, exactly, and had just heard it used to describe altering an image in general.

I happened upon a list of figures that display lots of information about who majors in science and engineering (S&E), all available at the NSF page on Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering. All are for institutions in the U.S. only, as far as I can tell.

Here we see the number of bachelor’s degrees in S&E and non-S&E fields, by sex:

Percent of S&E and non-S&E bachelor’s degrees earned by racial minorities:

Number of doctoral degrees earned by sex:

Percent of female workers in selected occupations in 2007:

Percent of S&E Ph.D.-holding employees at 4-year colleges and universities that are women:

Notice that while women are pretty well represented among “full-time tenured or tenure-track faculty,” they make up barely 15% of “full-time full professors with children,” “married full-time full professors,” and “full-time full professors at research institutions.” Some of this may be a matter of time, in that because being promoted to full professor takes years, an increase in the number of women getting Ph.D.s in a particular field will take a while to show up as a similar increase in number of women as professors in that field, everything else being equal.

But everything else isn’t equal. Women, even highly-educated ones, still do the majority of childcare and housework, and are more likely than men to consider how potential jobs could conflict with future family responsibilities when they are deciding what type of career to choose. So the lower proportion of female full professors at research institutions is likely a combination of some old-school unfriendliness to women in some departments, but also of women opting out of those positions–that is, deciding that the time and energy required to get tenure in a science/engineering department at a research school would conflict too much with family life, so they pursue other career options (for instance, women make up a higher proportion of faculty at community colleges, which are often perceived as being easier to get tenure at, since you don’t necessarily have to do lots of publishing–though anyone who has ever taught 5 courses a semester may question the assumption that it takes less time and work to teach than to publish).

And of course some women try to combine a tenure-track job with their family responsibilities and find it difficult, and either leave academia voluntarily or are turned down for tenure because they have not published enough or are not see as adequately involved and committed. Because of inequalities in the family, men are less likely to face those situations, though certainly some do.

I wish the report had a graph for non-S&E faculty, although it might just depress me.

UPDATE: Commenter Sarah says,

Check out the report “Women in Science: Career Processes and Outcomes” by Yu Xie and Kimberlee A. Shauman. They find no evidence to support the hypothesis that women are under-represented at the tenure level due to a lag between getting PhDs and acquiring tenure track positions. In the life sciences, women have been getting PhDs at the same rate as men for many years now, but inequality persists at the tenure-track level. Xie and Shauman find that a variety of social factors are responsible for actively hindering women at the highest levels of academia.

When considering which media text I wanted to analyze based on its ideology, I immediately thought about the unsettling yet intriguing relationship between the main characters in one of my favorite TV shows of all time: Mulder and Scully from The X-Files. About a year ago, I began watching the show when a friend bought the entire series on DVD. Despite the fact that I absolutely loved almost every episode, the story arc of these two main characters as co-workers and a couple reinforces tired gender roles.

The below clip is a climactic scene where Mulder and Scully argue about Scully leaving the X-Files in the 1998 film “The X-Files: Fight the Future.” I think this scene exemplifies their basic relationship, and is a good example of what I would like to analyze.

[youtube]https://youtu.be/esJNnh-d2E0[/youtube]

What I like about Scully is that she is intelligent, scientific, and witty. She joins up with Mulder to be the counterpart to his obsessive interest in the paranormal. Since Scully is the fact-spouting hard ass of the two, one might think the character is breaking stereotypes. Unfortunately, she is only obscuring them.

Scully plays a traditional mother figure to Mulder more so than his love interest. She continually questions her work in the FBI duo, but she stays because Mulder needs her. In her, he has found someone who tries to understand his work, someone to care for him, and someone to love him unconditionally. The few times that she has an interest in other men is when she is trying to get over Mulder or get back at him.

Throughout the series, the fact that Mulder is a “typical bachelor” is driven home. He’s quirky and boyish. He never cooks, he’s obsessed with baseball and porn, he can’t keep house, and he usually just sleeps on his couch. Scully is seemingly unconcerned by all this. She laughs it off when he flirts with other women, she rolls her eyes at his housekeeping, and she is always there whenever Mulder decides he needs her.

The video above is an example of a sort of backwards rationale. Yes Mulder is thanking Scully for being there for him, but he’s also pleading with her to continue to deprive her own happiness. Though the scene directly references her giving up her own interests to be with him, it also romanticizes the concept of a woman selflessly caring for her man. The scene resonates with his emotional “thank you” and begs the viewer and Scully to come to his rescue. It reinforces the idea that in order for a woman to be perfect for a man, she must be willing to do anything for him at all costs and should never as for anything in return. If he so much as thanks her for years of servitude, then he’s the knight in shining armor. Read it as: The perfect women are level-headed and enjoy cleaning up the messes that their boy-in-a-man’s-body significant others create without any appreciation.

I think the X-Files is a good example of a show that manages to skirt the issue of gender roles by throwing a few curve balls. In reality though, it’s just more of the same.

————————–

Sarah Mick is a student at the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee. She is currently double majoring in graphic design and media studies. She enjoys playing music, writing, and consuming media of various sorts in her spare time. I found her post here, where students in a Principles of Media Studies class are posting their insights. Special thanks to the instructor, Michael Newman, for facilitating the blog and allowing all of us to enjoy it!

If you would like to write a post for Sociological Images, please see our Guidelines for Guest Bloggers.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

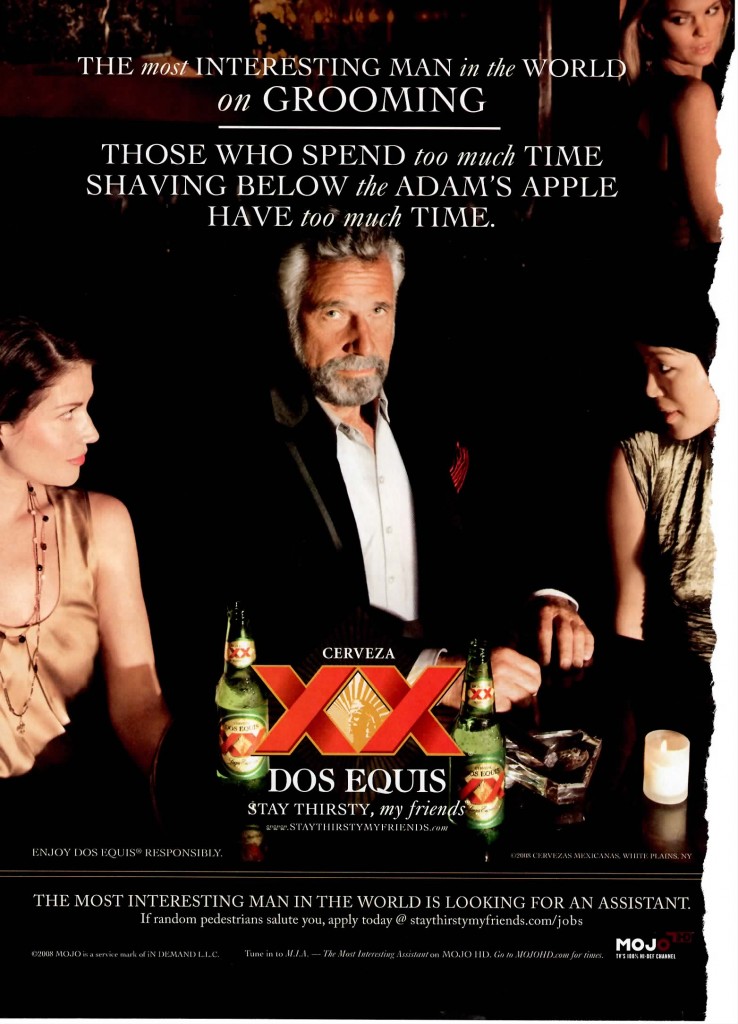

Here is an ad from the “Most Interesting Man in the World” ad campaign by Dos Equis:

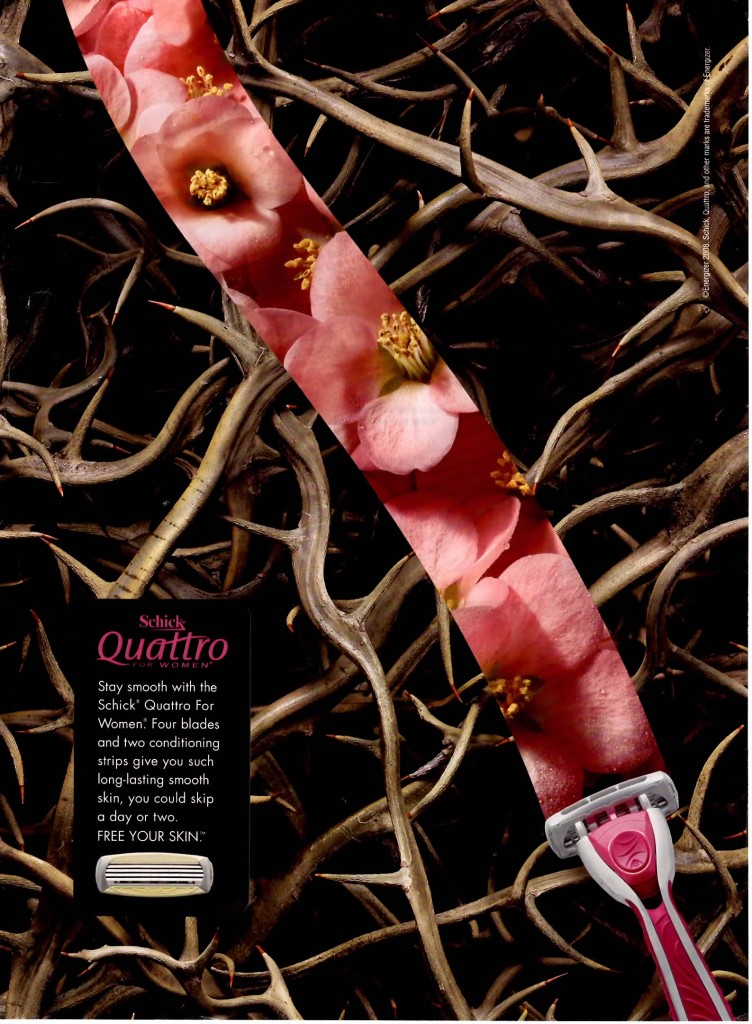

This ad, which is a clear attempt to harken back to the halcyon days of unfettered masculinity, is a cautionary tale against the feminizing effect of men shaving their body hair. Contrast this message with that of the following ad for the Schick Quattro:

Since the razor is pink, we can safely assume that it’s intended for women to use when converting their spiky brambles into beautiful flowers.

So, men aren’t supposed to shave below the neck, but women are required to. Specifically, women are supposed to shave their “flowers” (in a nod to vulva-as-flower imagery?).

This may be helpful in discussions about social norms related to the removal of pubic hair. Of particular interest is whether the expectation of women’s pubic hair removal is objectively different from the expectation that they will remove other body hair. Although pubic hair is considered more “private,” it’s difficult to make the argument that the impact of removing it is more sexual than that of, say, removing armpit hair (given that women’s attractiveness is partially predicated on the illusion of hairlessness). Also, some men are beginning to remove their pubic hair (and the Most Interesting Man in the World be damned). Is this a positive shift, suggesting some parity in beauty standards, or is it a negative shift, in that superficial cosmetic norms now have the power to leapfrog over the traditional bastion of masculinity?

Below are screenshots of the Degree Men, Degree Women, and Degree Girl websites.

Degree genders their deodorant with color (turquoise and lavender versus blue and yellow), pattern (bold lines versus curving spirals), language (women are “emotional” and men “take risks”). Really, Degree? We’re still going there?

Even the scents are gendered and, further, they reveal how we place men and women in a hierarchy (e.g., “Extreme Blast” versus “Summer Rain”). Men even get a scent called “Power.”

Degree also markets their product differently towards adult and t(w)een girls. Women are “emotional,” girls are “OMG!” let’s dance!!!

OMG! Let’s take a look!

“DEGREE MEN. PROTECTS MEN WHO TAKE RISKS.”

“Absolute Protection.”

“Responds to increases in adrenaline.”

“Proven at the hottest temperature on earth.”

“Unbeaten in competitive dryness testing.”

Scents include “Cool Rush,” “Extreme Blast,” “Arctic Edge,” “Intense Sport,” “Clean Reaction,” and “Power.”

“DEGREE WOMEN. DARE TO FEEL.”

“Emotional sweat can cause body odor more than perspiration from physical activity… you need extra odor protection to kick in when you’re stressed or emotional.”

Scents include “Classic Romance,” “Spring Fusion,” and “Fresh Oxygen,” “Pure Satin,” “Delicious Bliss,” and “Sexy Intrigue.”

“DEGREE GIRL. PROTECTION FOR EVERY OMG! MOMENT.”

“Crazy, exciting or embarrassing, OMG! moments happen to everyone.”

“Sign up 4 Cool Stuff! OMG SIGN UP.”

Scents include “Fun Spirit,” “Tropical Power,” and “Just Dance.” See also “Pink Crush.”

Also in dumb gendered marketing: Redken for men, make up for men, Frito Lay targets the ladies, nature versus the beast, it may be pink, but it’s not girly, gendered vitamins, and RISK (for men only).

Also in marketing towards tweens: “My Life” involves getting a boyfriend, teenager+colonialism = weird, and Nair for tweens.

Katie M. sent in a link to a post at Vast Public Indifference about gender in Pixar films, specifically how they tend to focus on male characters, with female characters in smaller or supporting roles. As Caitlin says in the original post,

The Pixar M.O. is (somewhat) subtler than the old your-stepmom-is-a-witch tropes of Disney past. Instead, Pixar’s continued failure to posit female characters as the central protagonists in their stories contributes to the idea that male is neutral and female is particular. This is not to say that Pixar does not write female characters. What I am taking issue with is the ad-nauseam repetition of female characters as helpers, love interests, and moral compasses to the male characters whose problems, feelings, and desires drive the narratives.

Here are some images showing main characters from a number of Pixar films. Clearly there are a lot I left out; I chose these both because they were mentioned in the original post by Caitlin, because I’ve seen them, and because they illustrate the general trend.

From “Cars,” a movie in which almost all the characters are male and female characters are mostly car-groupies who swoon over the main character (though there is a female attorney car who doesn’t fall into that category):

“Monsters, Inc.,” where the two central characters are male:

“Toy Story,” same as above:

“A Bug’s Life,” in which not only is the main character male, the actual behaviors of male and female ants have been switched to fit in with our ideas of appropriate gender roles (for another example of changing the behavior of animals to fit human gender norms, see this post on “Bee Movie”):

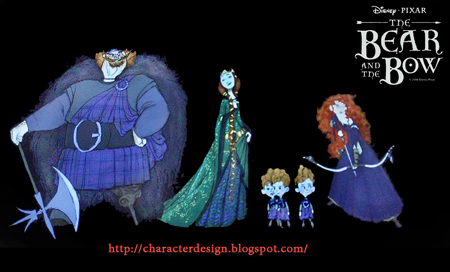

We do see a Pixar film with a female main character, however: the upcoming”The Bear and the Bow”:

According to Wikipedia, this is Pixar’s “first fairy tale.” So apparently though we get a female lead here, she’s of the spunky-princess type often found in fairy tales.

I have read, in discussions of gender in children’s films, that there is a general belief in the industry that everyone will watch a movie with a male lead character, but boys will be turned off by movies with a female lead. So we see the pattern Caitlin points out: males are the neutral category that are used when the movie is meant to appeal to a broad audience, while females get the lead mostly when the movie is specifically geared toward girls. The assumption here is that girls learn to look at the world through the male gaze (identifying with and liking the male lead, even though he’s male), while boys aren’t socialized to identify with female characters (or actual girls/women) in a similar manner.

I’m torn as to whether I think boys would avoid movies that had female leads. On the one hand, a big part of masculinity is rejecting all things feminine, so I can imagine boys deciding they hated any movie that seemed to be for or about girls. On the other hand, I wonder what would happen if we had more films aimed at kids that had female leads but didn’t fall into the traditional “girl’s movie” categories (such as fairy tales). If “A Bug’s Life” had a female lead but was otherwise the same type of movie–one aimed at a general audience, not specifically girls–would boys reject it? Most of the animated movies I can think of that had females as the main character were focused around romance and other topics deemed feminine (except maybe “Mulan,” where that’s not the main focus), which obscures the issue of whether boys would watch a movie with a female character if it was treated as a general-audience movie. [Note: See the comments for some other examples of movies with female leads that weren’t necessarily romantic-centered, such as “Lilo & Stitch” and “Alice in Wonderland,” as well as some non-animated ones.]

I dunno. Thoughts?

UPDATE: In the comments, Benjamin L. makes a great point:

Something to consider is that most of the people working on Pixar films are men. It’s possible that they might feel unable to successfully create and write dialog for compelling female characters. Take a look at this list: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Pixar_films Out of the all the writers and directors of Pixar’s films, one is female–Rita Hsiao. Significantly, the films she has worked on, Mulan and Toy Story 2, are unique in that they both have prominent female characters.