The “Let’s Move” campaign is Michelle Obama’s initiative to curb the childhood obesity epidemic in the United States. According to the campaign website, its goals include “creating a healthy start for children” by empowering their parents and caregivers, providing healthy food in schools, improving access to healthy, affordable foods, and increasing physical activity. Here is an example of the kind of “social marketing” that the campaign is releasing:

This campaign video is particularly notable for 1) its raced, classed, and gendered assumptions about the responsibility for promoting physical activity among young people; 2) the way it emphasizes personal responsibility while ignoring structural determinants of health; and 3) its Foucauldian implications (for the real social science nerds out there).

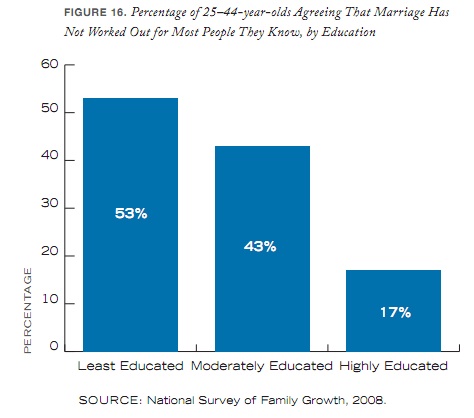

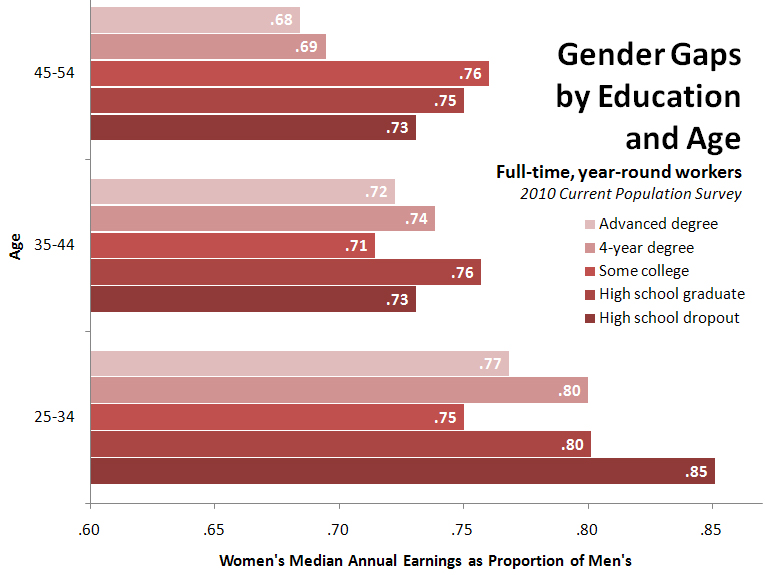

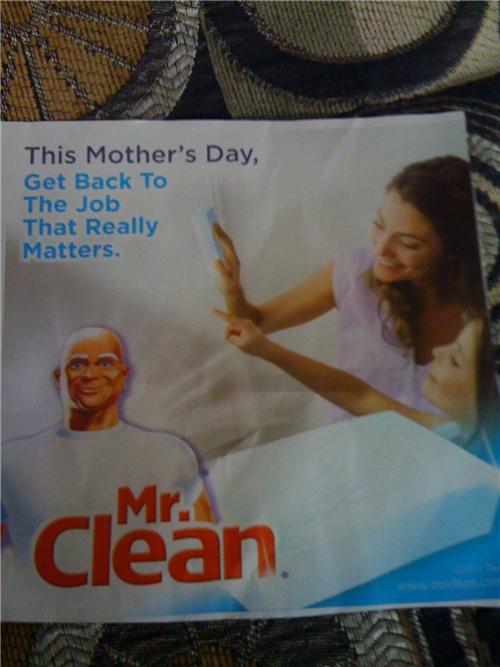

First, the video portrays a middle-aged white mother (in the kitchen, no less) who encourages her daughter to get exercise by having her running around their (apparently large, middle-class suburban) home in order to find the $1 she asked for. It ends by stating: “Moms everywhere are finding ways to keep kids healthy.” Not only does this assume that “moms” (not “parents”) have responsibility for keeping their kids healthy through intensive mothering practices, it fails to account for the fact that the childhood obesity epidemic (itself a social construct in many ways) is greatly stratified by race and socio-economic status. It is not clear to the viewer how they might encourage their children to exercise if they live, say, in a small apartment or a neighborhood without safe places for kids to play outside.

Second, a growing body of research points to the fact that structural-level inequalities, not individual-level health behaviors, account for the majority of poor health outcomes. This research illuminates a disconnect in most health promotion initiatives — people have personal responsibility (engage in physical activity) for structural problems (poverty; the high price of nutritious food; safe, well-lit, violence-free places for kids to play).

Finally, the video illustrates what some social scientists have noted about new forms of power in modern public health practice — for example, health promotion campaigns such as this one can be thought of as the exercise of “biopower,” or Foucault’s term for the control of populations through the body: health professionals and/or the government are entitled by scientific knowledge/power to examine, intervene, and prescribe “healthy lifestyles.” In this example, the campaign uses marketing strategies to remind the (very narrowly defined) audience of their duty to engage with dominant health messages and concerns (i.e., childhood obesity) through the control of bodies (that is, their children’s).

In the “Let’s move” campaign video, then, we see that (white, middle-class) moms have a responsibility for encouraging their children to get physical activity without an acknowledgement of the gendered expectations of caregiving, structural determinants of health that effect childhood obesity, and the implications of top-down control of the body.

————————

Christie Barcelos is a doctoral student in Public Health/Community Health Education at the University of Massachusetts Amherst where she studies social justice and health, critical pedagogy, and epistemology in health promotion.

If you would like to write a post for Sociological Images, please see our Guidelines for Guest Bloggers.