Today is the anniversary of the 34th American presidential election. The year was 1920; it was the first presidential election in which women were allowed their own votes. This seems like a good day to post a memento from the political battle over women’s suffrage, the right to vote and run for political office.

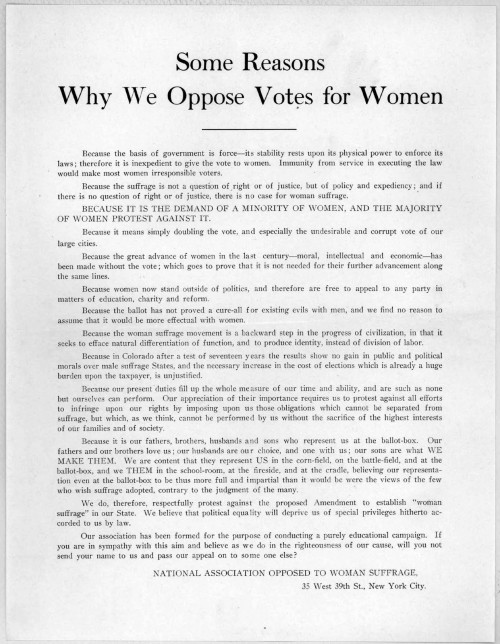

The fight for suffrage took decades and women were on both sides of the issue. The document below is a copy of an argument against women’s suffrage — Some Reasons Why We Oppose Votes for Women — printed in 1894. The National Association Opposed to Women’s Suffrage was led by Josephine Dodge. (Open and click “full size” to read.)

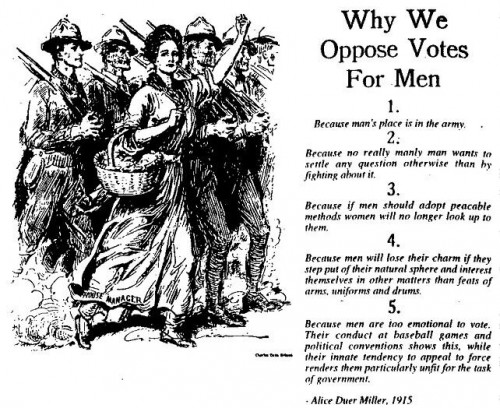

Alice Duer Miller was on the other side of the fight. In 1915, she wrote and circulated a satirical response titled Why We Oppose Votes for Men. Drawing on parallel logic, she made a case for why it was men, not women, who shouldn’t be voting. (Click for a larger copy.)

1. Because man’s place is in the army.

2. Because no really manly man wants to settle any question otherwise than by fighting about it.

3. Because if men should adopt peacable methods women will no longer look up to them.

4. Because men will lose their charm if they step out of their natural sphere and interest themselves in other matters than feats of arms, uniforms and drums.

5. Because men are too emotional to vote. Their conduct at baseball games and political conventions shows this, while their innate tendency to appeal to force renders them particularly unfit for the task of government.

It helps to have a sense of humor.

Happy anniversary of the first gender inclusive American presidential election everyone.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.