While the first flight attendants were male and many early airlines had a ban on hiring women, flight attending would eventually become a quintessentially female occupation. Airline marketers exploited the presence of these female flight attendants. Based on my reading — especially Phil Tiemeyer‘s Plane Queer and Kathleen Barry’s history of flight attendants’ labor activism — there seem to have been three stages.

First, there was the domestication of the cabin. As air travel became more comfortable (e.g., pressurized cabins and quieter rides), airlines were looking to increase their customer base. Female “stewardesses” in the ’40s and ’50s were an opportunity to argue that an airplane was just like a comfortable living room, equally safe for women, children, and men alike. Marketing at the time presented the flight attendant as if she were a mother or wife:

Twenty years later, air travel was no longer scary, so airlines switched their tactics. They sexualized their flight attendants in order to appeal to businessmen, who still made up a majority of their customers. Here’s a ten-second Southwest commercial touting the fact that their stewardesses wear “hot pants”:

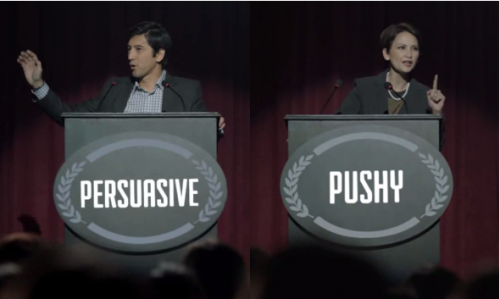

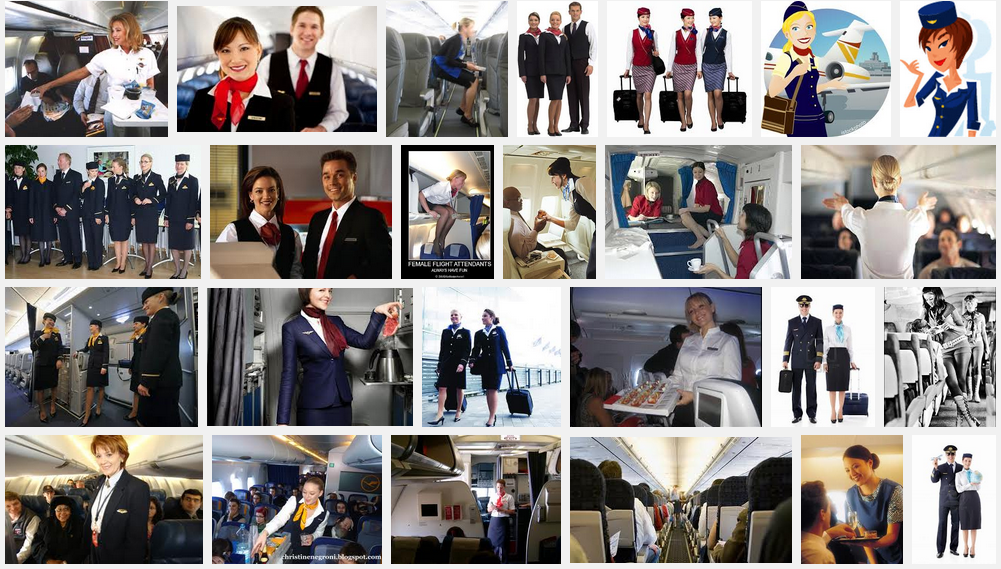

The intersection of the labor movement and women’s liberation in the ’60s and ’70s inspired women to fight for workplace rights. Flight attendants were among the first female workers to organize on behalf of their occupation and among the most successful to do so. Their work won both practical and symbolic victories, like the discursive move from “stewardess” to “flight attendant” that transformed women in the occupation from sex objects to workers. A quick Google Image search shows that the association — stewardess/sex object vs. flight attendant/worker — still applies. Notice that the search for “stewardess” includes more sexualized images, while the one for “flight attendant” shows more images of people actually working.

“Stewardess”:

“Flight attendant”: My impression is that today’s marketing tends to feature flight attendants in all three roles — domestic, sex object, worker — echoing each stage of the transformation of the occupation in the public imagination.

My impression is that today’s marketing tends to feature flight attendants in all three roles — domestic, sex object, worker — echoing each stage of the transformation of the occupation in the public imagination.

Cross-posted at The Huffington Post, Pacific Standard, and Work in Progress.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.