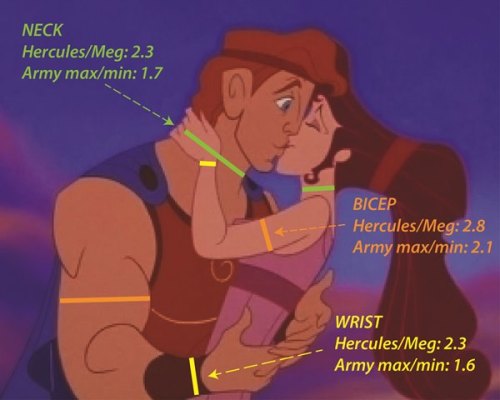

I know, I know, Hercules is a demi-god. But he’s also all man. In Disney’s (1997) version, Hades says to Megara, “I need someone who can — handle him as a man.” And handle him she does:

And since they involve him in such matters of the human flesh (and heart), that means their measurements are fair game for the Disney dimorphism series. If Disney is going to eroticize the relationship and sell it to innocent children, then we should ask what they’re selling.

As usual, they’re selling extreme sex dimorphism. I did some simple measurements from one pretty straight shot in the movie, and compared it to this awesome set of measurements taken of about 4,000 U.S. Army men and women in the late 1980s. Since Hercules is obviously extremely strong and this woman seems to be on the petite side, I compared their measurements to those of the biggest man versus the smallest woman on each dimension in the entire Army sample. The numbers shown are the man/woman ratios: Hercules/Meg versus the Army maximum/minimum.

As you can see, this cartoon Hercules is more extremely big compared to his cartoon love interest than even the widest man-woman comparison you can find in the Army sample, by a lot. (Notice his relaxed hands – he’s not flexing that bicep.)

To show how unrealistic this is, we can compare it to images of the actual Hercules. Here’s one from about 1620 (“Hercules slaying the Children of Megara,” by Allessandro Turchi):

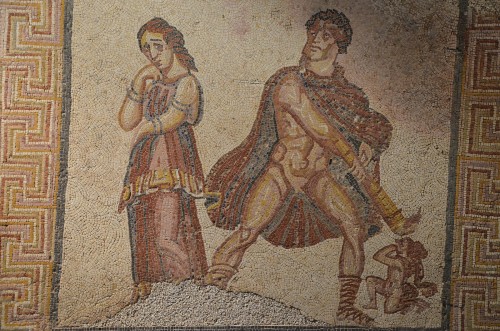

That Hercules is appallingly scrawny compared with Disney’s. Here’s another weakling version, from the 3rd or 4th century:

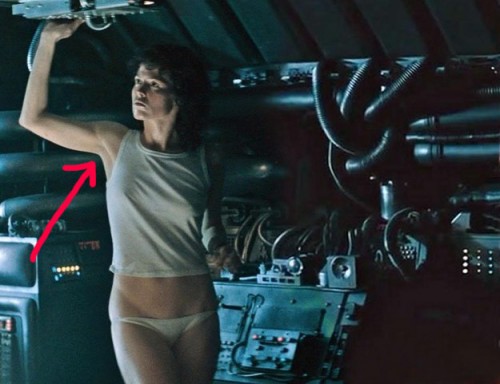

Now here is one from the 2014 Paramount movie, in which he is conveniently paired with the human female, Ergenia:

That bicep ratio is only 1.5-to-1. And that’s not normal.

Seriously, though, isn’t it interesting that both the Disney and the Paramount versions show more extreme dimorphism than the ancient representations? Go ahead, tell me he’s a demigod, that it’s a cartoon, that it’s not supposed to be realistic. I have heard all that before, and responded with counterexamples. But that doesn’t explain why the modern versions of this myth should show more sex dimorphism than the old-school ones. That’s progress of a certain kind.

I’ve written so far about Frozen and Brave, Tangled, and Gnomeo and Juliet, and How to Train Your Dragon 2. It all goes back to the critique, which I first discussed here and Lisa Wade described here, of the idea that male and female humans aren’t just different, they’re opposites. This contributes to the idea that Mark Regnerus defends as the “vision of complementarity” — the insistence that children need a male and female parent — which drives opposition to same-sex marriage. If men and women are too similar, then we wouldn’t need them to be paired up in order to have complete families or sexual relationships.

In the more mundane aspects of relationships — attraction and mate selection — this thinking helps set up the ideal in which women should be smaller than men, the result of which is pairing couples by man-taller-woman-shorter much more than would occur by chance (I reported on this here, but you also could have read about it from 538’s Mona Chalabi 19 months later). The prevalence of such pairs increases the odds that any given couple we (or our children) observe or interact with will include a man who is taller and stronger than his partner. This is also behind some notions that men and women should work in different — and unequal — occupations. And so on.

So I’m not letting this go.

Philip N. Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park. He is the author of The Family: Diversity, Inequality, and Social Change and writes the blog Family Inequality, where this post originally appeared. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook.