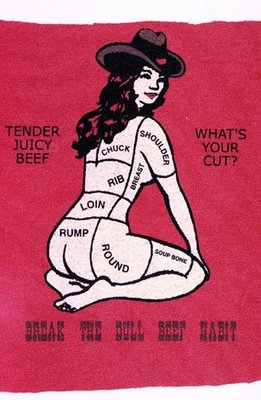

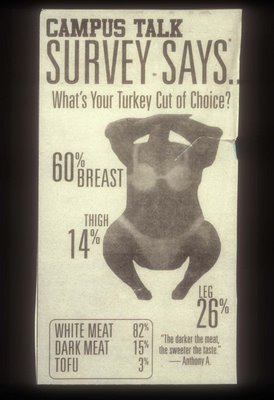

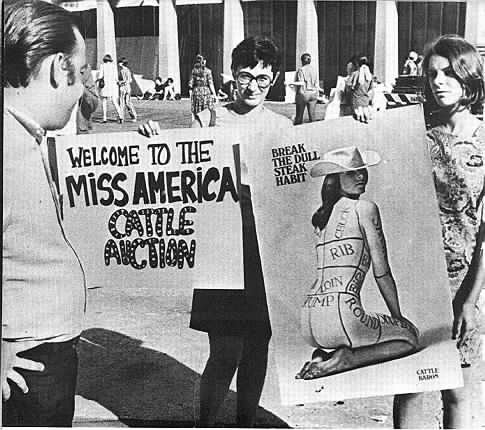

Carol Adams has written extensively on the sexual politics of meat, arguing that women and other animals are both sexualized and commodified to facilitate their consumption (both figuratively and literally) by those in power. One result has been the feminization of veganism and vegetarianism. This has the effect of delegitimizing, devaluing, and defanging veganism as a social movement.

Carol Adams has written extensively on the sexual politics of meat, arguing that women and other animals are both sexualized and commodified to facilitate their consumption (both figuratively and literally) by those in power. One result has been the feminization of veganism and vegetarianism. This has the effect of delegitimizing, devaluing, and defanging veganism as a social movement.

This process works within the vegan movement as well, with an open embracing of veganism as inherently feminized and sexualized. This works to undermine a movement (that is comprised mostly of women) and repackage it for a patriarchal society. Instead of strong, political collective of women, we have yet another demographic of sexually available individual women who exist for male consumption.

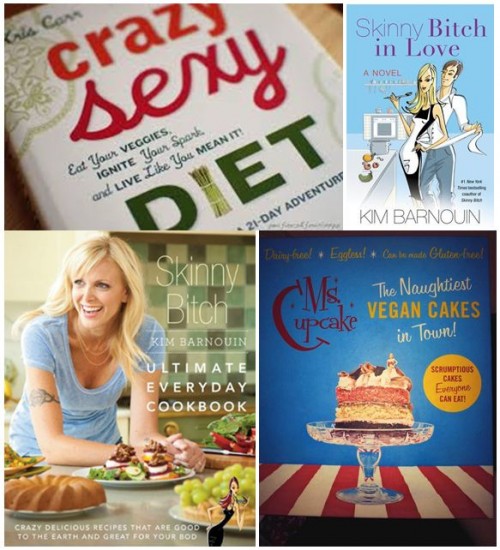

Take a browse through vegan cookbooks on Amazon, for instance, and the theme of “sexy veganism” that emerges is unmistakable:

Oftentimes, veganism is presented as a means of achieving idealized body types. These books are mostly geared to a female audience, as society values women primarily as sexual resources for men and women have internalized these gender norms. Many of these books bank on the power of thin privilege, sizism, and stereotypes about female competition for male attention to shame women into purchasing.

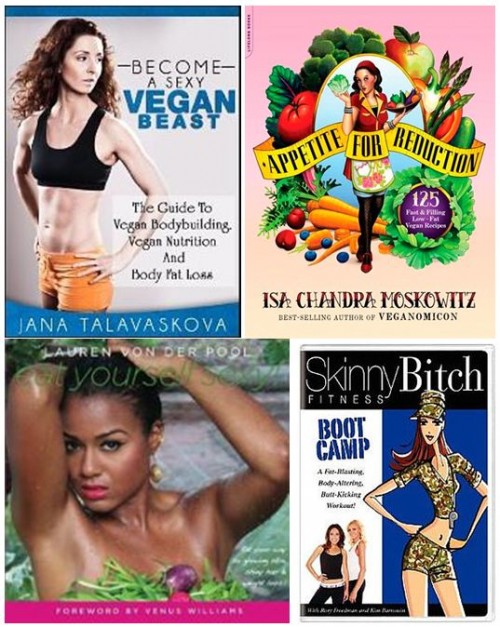

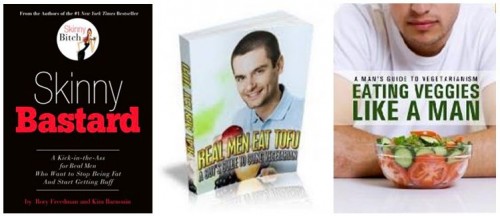

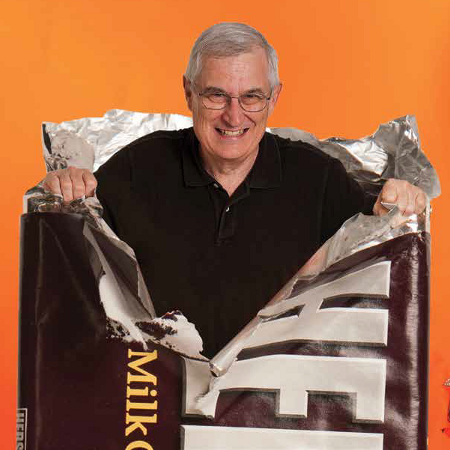

To reach a male audience, authors have to draw on a notion of “authentic masculinity” to make a highly feminized concept palatable to a patriarchal society where all that is feminine is scorned. Some have referred to this trend as “heganism.” The idea is to protect male superiority by unnecessarily gendering veganism into veganism for girls and veganism for boys. For the boys, we have to appeal to “real” manhood.

Meat Is For Pussies (A How-to Guide for Dudes Who Want to Get Fit, Kick Ass and Take Names) appears to be out of print, but there are others:

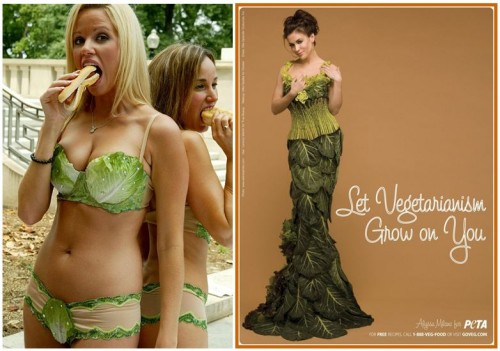

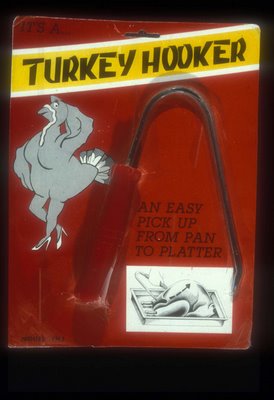

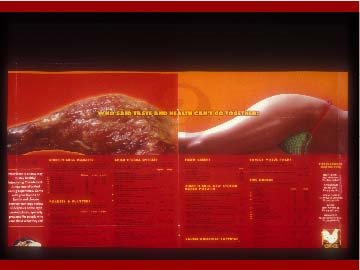

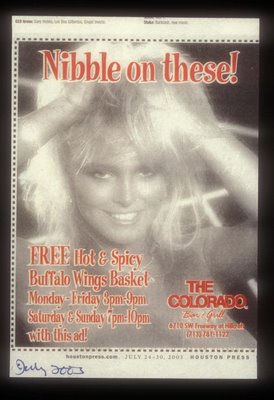

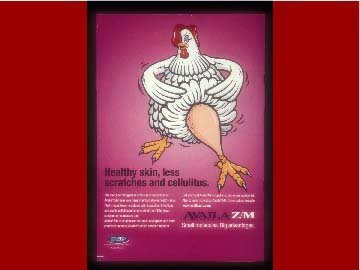

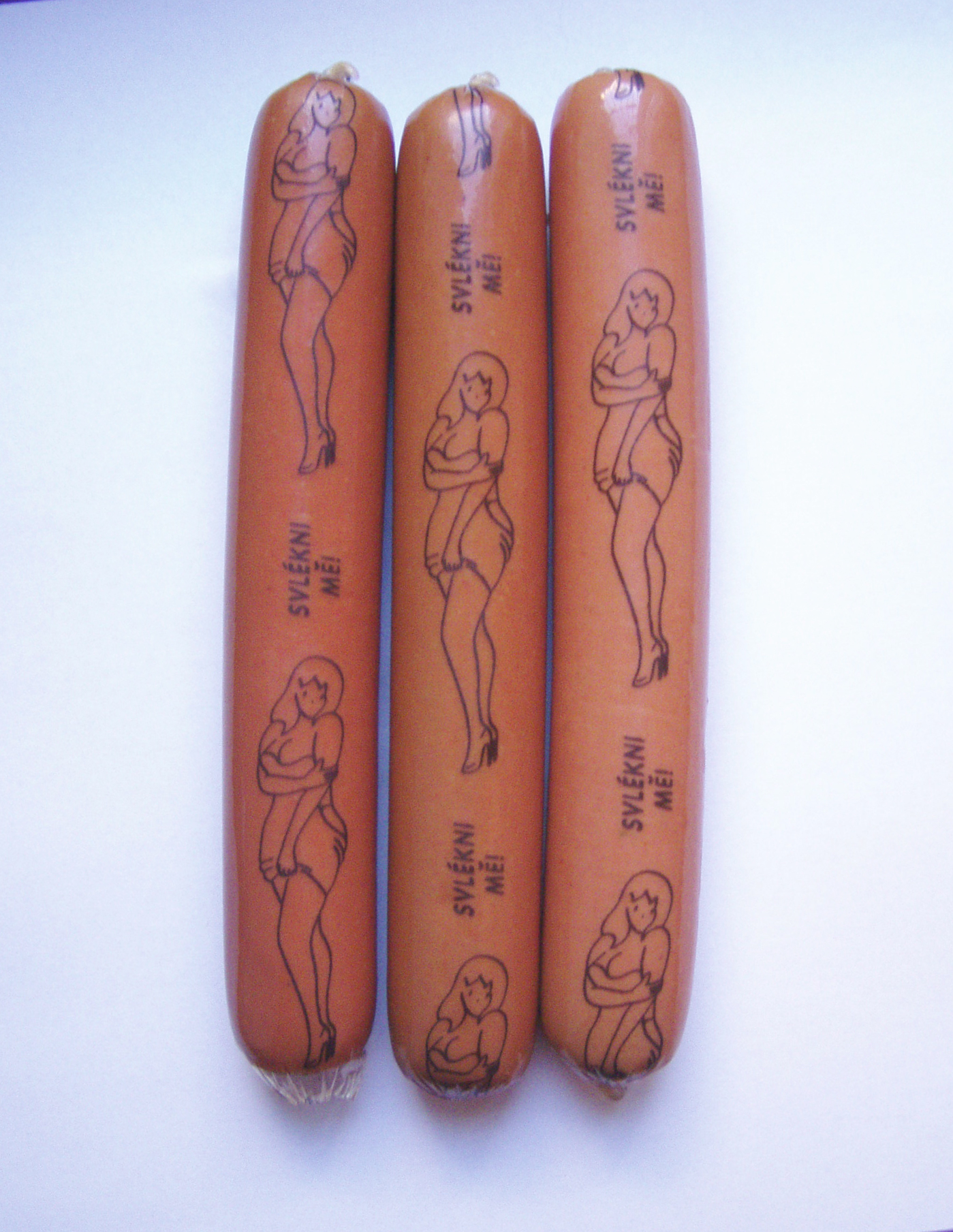

Then there is the popular tactic of turning women into consumable objects in the exact same way that meat industries do. Animal rights groups recruit “lettuce ladies” or “cabbage chicks” dressed as vegetables to interact with the public. PETA routinely has nude women pose in and among vegetables to convey the idea that women are sexy food. Vegan pinup sites and strip joints also feed into this notion. Essentially, it is the co-optation and erosion of a women’s movement. Instead of empowering women on behalf of animals, these approaches disempower women on behalf of men.

In sum, vegan feminism argues that women and non-human animals are commodified and sexualized objects offered up for the pleasurable consumption of those in power. In this way, both women and other animals are oppressed under capitalist patriarchy. When the vegan movement sexualizes and feminizes vegan food, or replicates the woman-as-food trope, it fails to acknowledge this important connection and ultimately serves to repackage potentially threatening feminist collective action in a way that is palatable to patriarchy.

Corey Lee Wrenn is a Council Member for the American Sociological Association’s Animals & Society section. This section facilitates improved sociological inquiry into issues concerning nonhuman animals and is currently seeking members. Membership is $5-$10; you must be a member of the ASA to join.

Cross-posted at the Vegan Feminist Network and Pacific Standard.