Flashback Friday.

Jenn F. found herself faced with a “Lucky Taco” at the end of her meal at a Mexican restaurant. It contained the following wisdom: “Paco says, ‘A bird in hand can be very messy.'”

The Lucky Taco is, of course, a “Mexican” version of the Chinese fortune cookie with which most Americans (at least) are familiar. Jenn also sent the link to the company that makes them, the Lucky Cookie Company, and they have two other versions, the Lucky Cannoli and the Lucky Cruncher (meant to be, respectively, version inspired by Italians and the “tribal” [their term, not mine]). Behold:

So this company took the Chinese fortune cookie and re-racialized it…. three times over. Is this is an appropriation of Chinese culture?

Nope.

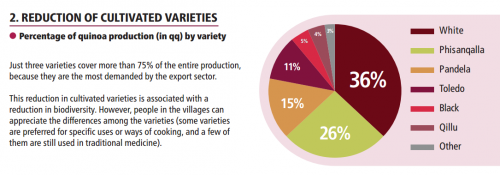

The fortune cookie isn’t Chinese. As best as can be figured out, it’s Japanese. But, in Japan, the fortune cookie wasn’t and isn’t like it is in the U.S. today. It’s larger and made with a darker batter seasoned with miso (instead of vanilla) and sprinkled with sesame seeds. This is a screenshot from a New York Times video about its history:

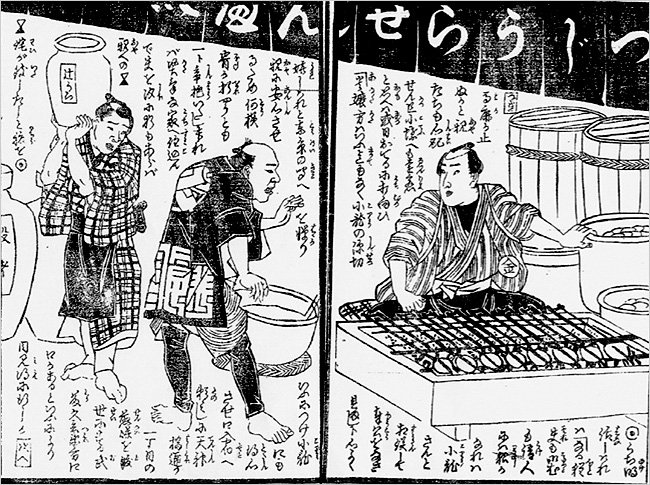

This drawing is believed to depict Japanese fortune cookie baking in 1878:

According to the New York Times, it was Japanese-Americans in California who first began making and selling fortune cookies in the ’20s. Many of them, however, served Chinese food. And Chinese-Americans may have picked up on the trend. Then, when the Japanese were forced into internment camps during WWII, Chinese-Americans took over the industry and, voila, the “Chinese fortune cookie.”

So the “Chinese” fortune cookie with which we’re all familiar isn’t Chinese at all and is certainly of American (re-)invention. So, insofar as the Lucky Taco, Lucky Cannoli, and the Lucky Cruncher are offensive — and I’m pretty sure they are — it’ll have to be for some other reason.

Originally posted in 2010.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.