Katrin sent along a vintage (apparently 1957) Pepsi commercial I thought you might enjoy, as it has all the classics: lightly mocking tone about women’s supposed competitiveness with one another and obsession with shopping, reminder that attractive = thin, and presentation of marriage as the ideal, ultimate victory for all women:

food/agriculture

Katie L. sent along a fascinating Starbucks commercial. In it, a succession of workers grow, harvest, roast, taste, and prepare coffee from scratch for a hypothetical customer named “Sue.” At first glance, I thought that the commercial did a nice job of at least acknowledging their workers (if in an overly romanticized way), unlike some commercials for agricultural products that erase them. But I thought again. Because the entire commercial revolves around Sue, the inclusion of all the workers isn’t meant to focus our attention on them, it’s meant to highlight how much work goes into pleasing Sue. We’re supposed to identify with Sue, not the series of workers.

This reminds me of a post about a “hand-rolled” tea sold at The Coffee Bean and Tea Leaf. The consumer was supposed to be excited about the tea not because of its flavor, but because, as I wrote, “it takes a significant amount of human labor to “hand-roll” tea leaves into balls… What could be more luxurious than the casual-and-fleeting enjoyment of the hard-and-long labor of others? ”

This ad has a similar feel. The workers are portrayed only in order to make the intended consumer feel special. They work with Sue in mind, tending carefully to Sue’s future pleasure intently and with care. They find satisfaction in Sue’s satisfaction. Sue is everything. Everyone is for Sue.

This tells us something interesting, no doubt, about American cultural values.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

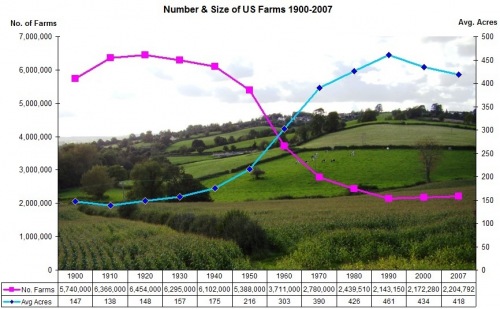

Recently I posted about the loss of genetic diversity in industrial agriculture, partially due to increasing concentration at every link in food commodity chains, from the farm to the grocery store. This image from the Centre for Research on Globalization, sent in by Rick T. of the University of Western Ontario, illustrates the process of concentration at the farm level. In the U.S., the total number of farms has fallen from an all-time high of over 6.3 million to just over 2.2 million. Meanwhile, the average size per farm nearly tripled between 1900 and 2007, from 147 to 418 acres.

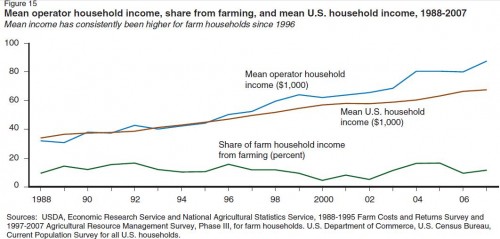

A 2010 USDA report provides detailed information about the structure of U.S. agriculture. For instance, overall, average farm household income is higher than the U.S. average, though I’d rather see the median income to reduce the impact of outliers on the calculation. But as the bottom line shows, farm households are highly dependent on non-farm income for their survival. Overall, farm income accounts for less than 20% of the total income of farming families:

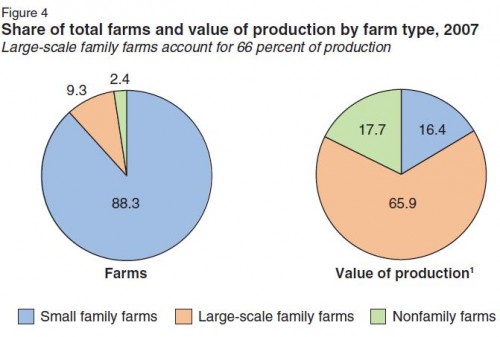

And as we saw recently with the mortgage interest deduction program, the benefits of farm subsidies are unevenly distribution. Small-scale family farms (defined as operator-owned farms with less than $250,000 in sales — which does not mean $250,000 in profit, of course) make up 88.3% of all farms in the U.S., while large-scale family farms (operator-owned farms with sales over $250,000) are 9.3%:

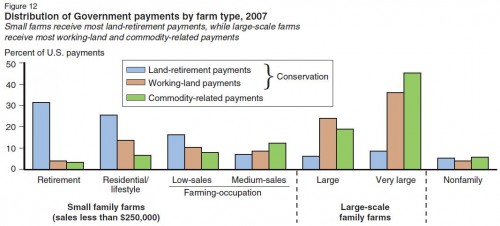

While small-scale family farmers receive the majority of land-retirement payments — that is, subsidies in return for taking land out of agricultural production — large-scale family farms are the major beneficiaries of commodity payments such as price supports that subsidize the cost of production:

Of course, that doesn’t mean that small-scale producers don’t benefit from farm subsidy programs, but as with the mortgage interest tax deduction, they are set up to reward size — the more you have, the more you get. Whether farm subsidies are essential to preserving small family farms or actually hurt them by artificially supporting capital-intensive large-scale production is a topic of much debate within agricultural circles.

In his classic 1973 overview of U.S. agribusiness and its effects on the food we eat, Hard Tomatoes, Hard Times, Jim Hightower discusses how the search for market efficiencies had changed the tomatoes Americans could buy in their local supermarkets. Tomatoes posed a number of problems for modern industrial agriculture; in particular, they tended to get bruised or smashed when harvested by machine and transported long distances. To facilitate mechanical harvest and shipping, varieties were developed that were harder and tougher — often at the expense of other qualities, such as taste. This same process has occurred with many crops. For instance, I can buy huge, bright red strawberries year-round in the U.S. these days, as long as I don’t mind that they have only a hint of the rich taste of the strawberries my grandma used to grow.

As a result of concentration in agribusiness (including grocery chains) and selection of varieties that can withstand the mechanical harvesting and long-distance shipping required by the industrial food system, we see fewer and fewer varieties of crops on the shelf. Despite the efforts of heritage seed banks and heirloom variety enthusiasts, many have disappeared altogether; others are dangerously close to doing so. It’s an enormous loss of genetic diversity, of varieties that were developed over many years based on flavor, resistance to pests, ability to withstand drought, frosts, or other environmental stresses, and so on.

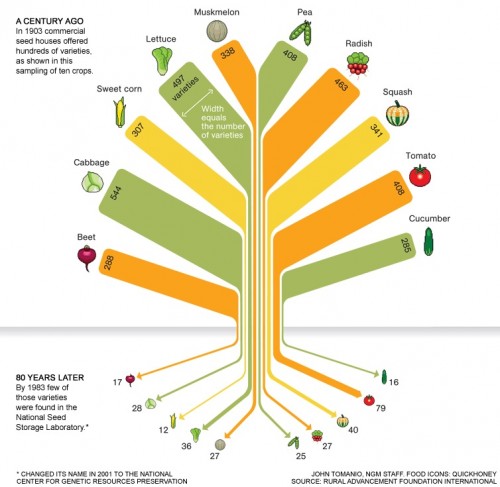

Dolores R. let us know that National Geographic posted an image based on a 1983 study by the Rural Advancement Foundation International that illustrates the loss of this genetic diversity. RAFI looked at a typical commercial seed catalog from 1903 — that is, a catalog of seeds targeting farmers producing for the market. They found a large number of varieties available.

But then they looked at the seed collection at the National Seed Storage Laboratory (now the National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation). This government entity is in charge of collecting and storing seeds to preserve genetic diversity among crops and livestock. The bottom half of this image shows how many of the varieties in the 1903 catalog were in the lab’s collection as of 1983:

Of course, the NCGRP isn’t the only organization storing seeds; many private groups, such as Seed Savers Exchange, preserve heirloom varieties. And many varieties have been introduced, such as the Round-Up Ready crops developed by Monsanto to be compatible with Round-Up weed killer. The NCGRP has also added greatly to its collection over time. Nonetheless, many varieties have simply disappeared, reducing the genetic diversity available in our current agricultural system and increasing the risks should a virulent pest or disease attack the dominant varieties of crops and livestock. For more on this, see the full National Geographic article.

I recently watched a reading of a play, New Jerusalem, with a cast of five men and two women. One woman was a love interest, the other was an emotional, screechy brat. By the end of the play I was so tired of the stereotype, I just wanted the play to end.

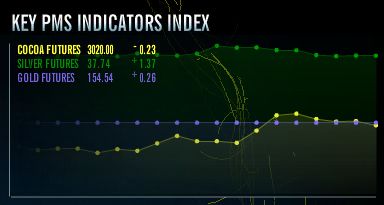

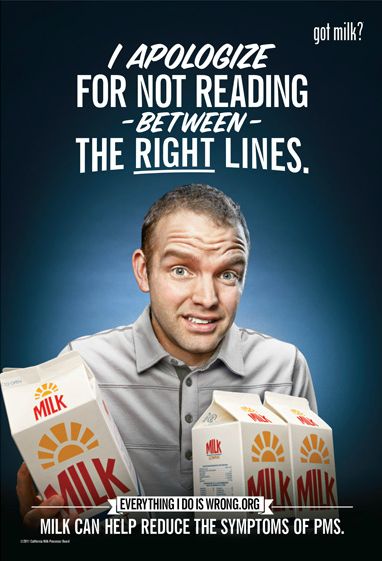

Thanks to Kristin, Christine, Amanda, Dolores R., Dmitriy T.M., and Nathan Meltz (whose awesome artwork we’ve previously featured), I am now aware that, coincidentally, this is the week that the California Milk Processor Board decided to roll out its new ad campaign. The campaign suggests that milk can save men from their cyclically bitchy girlfriends and wives. Milk, the claim is, helps alleviate the symptoms of PMS (but see this take down). And gawd knows there is nothing more annoying than an emotional, screechy, bitchy brat of a woman. Their website, Everything I Do is Wrong, asks “Are you a man living with PMS?” It links likelihood of PMS with the availability of chocolate, silver, and gold:

Tracks the “Global PMS Level”:

It suggests that women irrationally punish men for not knowing answers to trivial questions:

And purports to show men how to enhance their apologies with cheesy imagery and self-flagellation:

It’s overall a nasty soup of derogatory ideas about women and how unbelievably annoying they are to live with. Though, as Christine wrote, it’s also…

…sexist in the way that they stereotype men as ineffective communicators, who are terrified of emotional women and the “feminine mystique” of menstruation because they (obviously) lack the faculties with which to properly negotiate any disagreements they might have with the women in their lives.

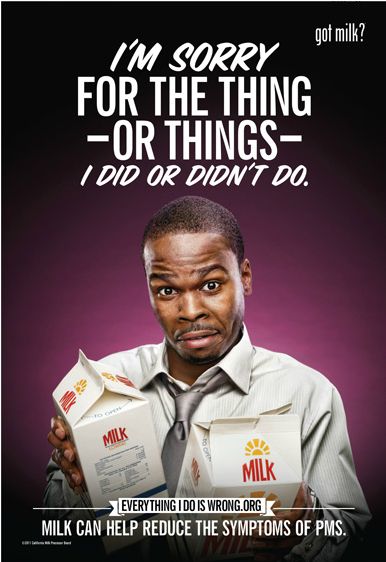

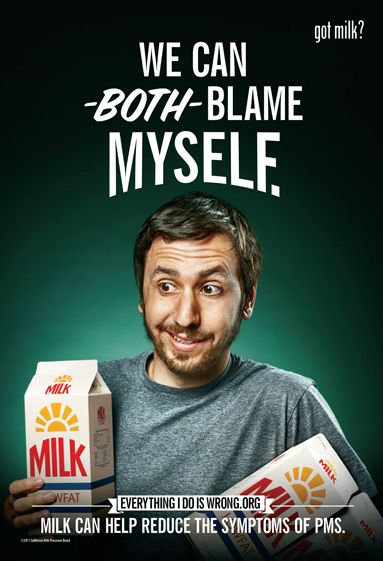

Here are some of the more delightful print ads:

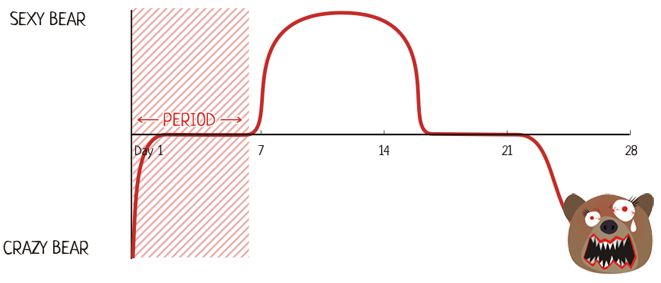

The stereotype is ubiquitous. You can also find it at The Daily Cramp, a website sent in by Janine P. that says it will track your woman’s menstrual cycle and let you know when you can expect her to act crazy:

There’s also an app with the same gimmick.

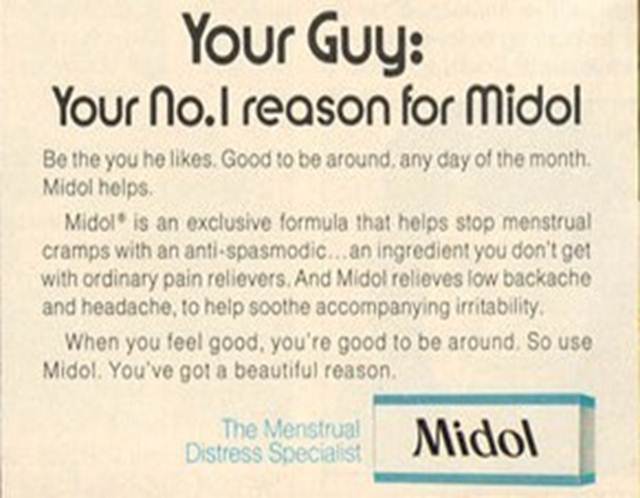

And it’s been around for a long time. This vintage ad for Midol, sent in by Jillian Y. and Lexi A.-L., tells women to medicate themselves on behalf of their “guy,” so they can be “good to be around, any day of the month”:

The problem with this stereotype is that it encourages people to see women as periodically irrational and also more generally dismiss-able. It allows us to conflate screechiness and bitchiness with being female.

The milk board’s commentary on the negative response has been, essentially, “Aw come on, it’s all in good fun! Can’t you take a joke!” I get, milk board, that this is humorous. I totally get that. It’s also an offensive stereotype. The two aren’t mutually exclusive.

See also: menstruation masculinizes women, a princess with pms who threatens to drown the land with her tears, delegitimating Hillary Clinton with pms-jokes, and our previous post on gender and the rest of the California Milk Processing Board’s website.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Dmitriy T.M. sent in a New York Times slideshow of the contents of “MREs” from different countries. MREs stands for “Meals Ready to Eat”; they are combat rations for soldiers. The rations are each some combination of comfort food, nutrition, and necessity. And the different contents across countries reveal some interesting similarities and differences.

All MREs include some sort of meat, but the type and form of the meat vary, from meatballs to paté. Meanwhile, almost all of the MREs include candy; it’s probably cheap, in the big scheme of things, to throw a few skittles, m&ms, or squares of chocolate, but what a treat it must be. Likewise, the fruit-flavored beverages and tea must be a taste of home. As for practicality, countries vary in whether they provide moist towelettes, toothpicks, tooth brushes. Most offer matches; the U.S. includes toilet paper.

That said, the content of rations are also strikingly consistent. I’ve love to see a flow chart tracing the development of MREs. Were the logics for these rations developed in isolation? Or were some countries influential over others?

These are my uneducated observations. Feel free to offer more informed thoughts in the comments.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

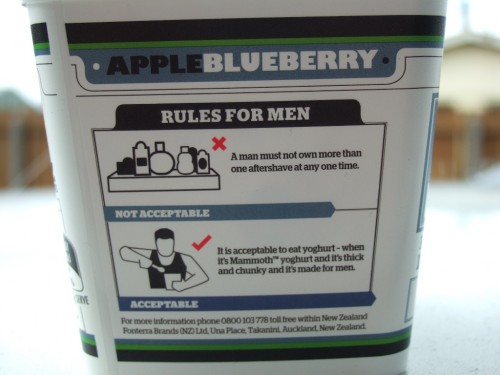

Jeremiah, Sarah S., Nikki R., and Erin H. sent us a great example of a company trying to make a feminized food safe for men. New Zealand’s Mammoth Supply Co. (a subsidiary of the multinational dairy giant Fonterra) is trying to convince men that yogurt is super manly and tough, “built to tame a man’s hunger.” The ads reinforce a whole range of rules about masculinity, which Erin nicely sums up as “the same old mythbashing that men need things that are big, tough, substantial, strong and rugged, and that coded-feminine activities (crying, being too involved in one’s personal appearance, coming into physical contact with people of the same sex) are inferior and weak”:

Via Copyranter.

The website, which assures the reader that this is “real man food, man,” as well as each carton of yogurt includes additional helpful tips:

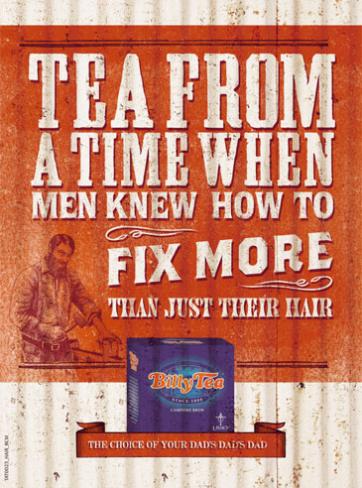

Lisa K. recently saw an ad for Billy Tea in a newspaper that implies men and women are no longer sufficiently masculine and feminine, unlike the good old days when the tea was first produced:

Here’s another one of their ads:

Sarah B. sent in this Miller High Life ad (which she blogged about at Adventures in Mediocrity) that makes it clear that the only types of salad men should eat are the type without, you know, girly vegetables:

In another example of gendering foods, Lisa R. pointed out Applebee’s commercials for its set of dishes with under 550 calories. Women love eating low-calorie meals:

The commercial aimed at men, titled “Manly Man,” presents ordering from the 550-calorie menu as something men might be a bit embarrassed about, but don’t worry — once the guys see your huge plate of food, your masculinity will once again be unquestioned:

Quite some time ago, Laura McD. sent us a link to an NPR story about a new ad campaign for baby carrots (which, if you didn’t know, aren’t actually immature carrots; they’re just regular carrots peeled and cut into small pieces). In an effort to appeal to teens, these ads openly satirize marketing tropes used to sell lots of snacks, especially the effort to market junk food as totally extreme! The website self-consciously makes the link to junk food, winking at the audience about the absurdity of EXTREEEEEME!!!!! marketing, yet hoping that rebranding carrots as similar to junk food, and using the marketing tactics they’re laughing at, actually increases sales. So, for instance, they have new packaging that looks like bags of chips:

The ads serve as a great primer on extreme food marketing cliches, complete with associations with violence (and stupidity), the sexualization of women, and the constant reminder via voiceovers and pounding music that this food is freakin’ extreme, ok?!?!

/p>

This one parodies ads that sexualize both women and food and present eating as an indulgence for women:

The ad campaign presents all this with a tongue-in-cheek tone of “isn’t this ridiculous?” But they’re also genuinely trying to rebrand a food product to increase sales, and clearly see the way to do that as downplaying any claims about health and instead using — if mockingly — the same marketing messages advertisers use to sell soda, chips, energy drinks, and other foods aimed at teens (particularly, though not only, teen boys).

As such, they provide a great summary of these marketing techniques and the jesting “Ha ha! We get it! We’re not like the other marketers who try to sell stuff to you! We know this is silly! (Please buy our product, though)” ironic marketing technique.

And now, I highly recommend you go watch the satire of energy drink commercials Lisa posted way back in 2007. It never gets old.

Katie L. sent along a fascinating Starbucks commercial. In it, a succession of workers grow, harvest, roast, taste, and prepare coffee from scratch for a hypothetical customer named “Sue.” At first glance, I thought that the commercial did a nice job of at least acknowledging their workers (if in an overly romanticized way), unlike some commercials for agricultural products that erase them. But I thought again. Because the entire commercial revolves around Sue, the inclusion of all the workers isn’t meant to focus our attention on them, it’s meant to highlight how much work goes into pleasing Sue. We’re supposed to identify with Sue, not the series of workers.

This reminds me of a post about a “hand-rolled” tea sold at The Coffee Bean and Tea Leaf. The consumer was supposed to be excited about the tea not because of its flavor, but because, as I wrote, “it takes a significant amount of human labor to “hand-roll” tea leaves into balls… What could be more luxurious than the casual-and-fleeting enjoyment of the hard-and-long labor of others? ”

This ad has a similar feel. The workers are portrayed only in order to make the intended consumer feel special. They work with Sue in mind, tending carefully to Sue’s future pleasure intently and with care. They find satisfaction in Sue’s satisfaction. Sue is everything. Everyone is for Sue.

This tells us something interesting, no doubt, about American cultural values.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Recently I posted about the loss of genetic diversity in industrial agriculture, partially due to increasing concentration at every link in food commodity chains, from the farm to the grocery store. This image from the Centre for Research on Globalization, sent in by Rick T. of the University of Western Ontario, illustrates the process of concentration at the farm level. In the U.S., the total number of farms has fallen from an all-time high of over 6.3 million to just over 2.2 million. Meanwhile, the average size per farm nearly tripled between 1900 and 2007, from 147 to 418 acres.

A 2010 USDA report provides detailed information about the structure of U.S. agriculture. For instance, overall, average farm household income is higher than the U.S. average, though I’d rather see the median income to reduce the impact of outliers on the calculation. But as the bottom line shows, farm households are highly dependent on non-farm income for their survival. Overall, farm income accounts for less than 20% of the total income of farming families:

And as we saw recently with the mortgage interest deduction program, the benefits of farm subsidies are unevenly distribution. Small-scale family farms (defined as operator-owned farms with less than $250,000 in sales — which does not mean $250,000 in profit, of course) make up 88.3% of all farms in the U.S., while large-scale family farms (operator-owned farms with sales over $250,000) are 9.3%:

While small-scale family farmers receive the majority of land-retirement payments — that is, subsidies in return for taking land out of agricultural production — large-scale family farms are the major beneficiaries of commodity payments such as price supports that subsidize the cost of production:

Of course, that doesn’t mean that small-scale producers don’t benefit from farm subsidy programs, but as with the mortgage interest tax deduction, they are set up to reward size — the more you have, the more you get. Whether farm subsidies are essential to preserving small family farms or actually hurt them by artificially supporting capital-intensive large-scale production is a topic of much debate within agricultural circles.

In his classic 1973 overview of U.S. agribusiness and its effects on the food we eat, Hard Tomatoes, Hard Times, Jim Hightower discusses how the search for market efficiencies had changed the tomatoes Americans could buy in their local supermarkets. Tomatoes posed a number of problems for modern industrial agriculture; in particular, they tended to get bruised or smashed when harvested by machine and transported long distances. To facilitate mechanical harvest and shipping, varieties were developed that were harder and tougher — often at the expense of other qualities, such as taste. This same process has occurred with many crops. For instance, I can buy huge, bright red strawberries year-round in the U.S. these days, as long as I don’t mind that they have only a hint of the rich taste of the strawberries my grandma used to grow.

As a result of concentration in agribusiness (including grocery chains) and selection of varieties that can withstand the mechanical harvesting and long-distance shipping required by the industrial food system, we see fewer and fewer varieties of crops on the shelf. Despite the efforts of heritage seed banks and heirloom variety enthusiasts, many have disappeared altogether; others are dangerously close to doing so. It’s an enormous loss of genetic diversity, of varieties that were developed over many years based on flavor, resistance to pests, ability to withstand drought, frosts, or other environmental stresses, and so on.

Dolores R. let us know that National Geographic posted an image based on a 1983 study by the Rural Advancement Foundation International that illustrates the loss of this genetic diversity. RAFI looked at a typical commercial seed catalog from 1903 — that is, a catalog of seeds targeting farmers producing for the market. They found a large number of varieties available.

But then they looked at the seed collection at the National Seed Storage Laboratory (now the National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation). This government entity is in charge of collecting and storing seeds to preserve genetic diversity among crops and livestock. The bottom half of this image shows how many of the varieties in the 1903 catalog were in the lab’s collection as of 1983:

Of course, the NCGRP isn’t the only organization storing seeds; many private groups, such as Seed Savers Exchange, preserve heirloom varieties. And many varieties have been introduced, such as the Round-Up Ready crops developed by Monsanto to be compatible with Round-Up weed killer. The NCGRP has also added greatly to its collection over time. Nonetheless, many varieties have simply disappeared, reducing the genetic diversity available in our current agricultural system and increasing the risks should a virulent pest or disease attack the dominant varieties of crops and livestock. For more on this, see the full National Geographic article.

I recently watched a reading of a play, New Jerusalem, with a cast of five men and two women. One woman was a love interest, the other was an emotional, screechy brat. By the end of the play I was so tired of the stereotype, I just wanted the play to end.

Thanks to Kristin, Christine, Amanda, Dolores R., Dmitriy T.M., and Nathan Meltz (whose awesome artwork we’ve previously featured), I am now aware that, coincidentally, this is the week that the California Milk Processor Board decided to roll out its new ad campaign. The campaign suggests that milk can save men from their cyclically bitchy girlfriends and wives. Milk, the claim is, helps alleviate the symptoms of PMS (but see this take down). And gawd knows there is nothing more annoying than an emotional, screechy, bitchy brat of a woman. Their website, Everything I Do is Wrong, asks “Are you a man living with PMS?” It links likelihood of PMS with the availability of chocolate, silver, and gold:

Tracks the “Global PMS Level”:

It suggests that women irrationally punish men for not knowing answers to trivial questions:

And purports to show men how to enhance their apologies with cheesy imagery and self-flagellation:

It’s overall a nasty soup of derogatory ideas about women and how unbelievably annoying they are to live with. Though, as Christine wrote, it’s also…

…sexist in the way that they stereotype men as ineffective communicators, who are terrified of emotional women and the “feminine mystique” of menstruation because they (obviously) lack the faculties with which to properly negotiate any disagreements they might have with the women in their lives.

Here are some of the more delightful print ads:

The stereotype is ubiquitous. You can also find it at The Daily Cramp, a website sent in by Janine P. that says it will track your woman’s menstrual cycle and let you know when you can expect her to act crazy:

There’s also an app with the same gimmick.

And it’s been around for a long time. This vintage ad for Midol, sent in by Jillian Y. and Lexi A.-L., tells women to medicate themselves on behalf of their “guy,” so they can be “good to be around, any day of the month”:

The problem with this stereotype is that it encourages people to see women as periodically irrational and also more generally dismiss-able. It allows us to conflate screechiness and bitchiness with being female.

The milk board’s commentary on the negative response has been, essentially, “Aw come on, it’s all in good fun! Can’t you take a joke!” I get, milk board, that this is humorous. I totally get that. It’s also an offensive stereotype. The two aren’t mutually exclusive.

See also: menstruation masculinizes women, a princess with pms who threatens to drown the land with her tears, delegitimating Hillary Clinton with pms-jokes, and our previous post on gender and the rest of the California Milk Processing Board’s website.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Dmitriy T.M. sent in a New York Times slideshow of the contents of “MREs” from different countries. MREs stands for “Meals Ready to Eat”; they are combat rations for soldiers. The rations are each some combination of comfort food, nutrition, and necessity. And the different contents across countries reveal some interesting similarities and differences.

All MREs include some sort of meat, but the type and form of the meat vary, from meatballs to paté. Meanwhile, almost all of the MREs include candy; it’s probably cheap, in the big scheme of things, to throw a few skittles, m&ms, or squares of chocolate, but what a treat it must be. Likewise, the fruit-flavored beverages and tea must be a taste of home. As for practicality, countries vary in whether they provide moist towelettes, toothpicks, tooth brushes. Most offer matches; the U.S. includes toilet paper.

That said, the content of rations are also strikingly consistent. I’ve love to see a flow chart tracing the development of MREs. Were the logics for these rations developed in isolation? Or were some countries influential over others?

These are my uneducated observations. Feel free to offer more informed thoughts in the comments.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

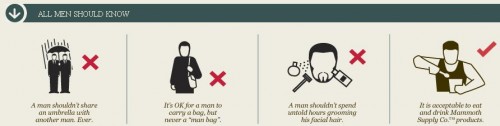

Jeremiah, Sarah S., Nikki R., and Erin H. sent us a great example of a company trying to make a feminized food safe for men. New Zealand’s Mammoth Supply Co. (a subsidiary of the multinational dairy giant Fonterra) is trying to convince men that yogurt is super manly and tough, “built to tame a man’s hunger.” The ads reinforce a whole range of rules about masculinity, which Erin nicely sums up as “the same old mythbashing that men need things that are big, tough, substantial, strong and rugged, and that coded-feminine activities (crying, being too involved in one’s personal appearance, coming into physical contact with people of the same sex) are inferior and weak”:

Via Copyranter.

The website, which assures the reader that this is “real man food, man,” as well as each carton of yogurt includes additional helpful tips:

Lisa K. recently saw an ad for Billy Tea in a newspaper that implies men and women are no longer sufficiently masculine and feminine, unlike the good old days when the tea was first produced:

Here’s another one of their ads:

Sarah B. sent in this Miller High Life ad (which she blogged about at Adventures in Mediocrity) that makes it clear that the only types of salad men should eat are the type without, you know, girly vegetables:

In another example of gendering foods, Lisa R. pointed out Applebee’s commercials for its set of dishes with under 550 calories. Women love eating low-calorie meals:

The commercial aimed at men, titled “Manly Man,” presents ordering from the 550-calorie menu as something men might be a bit embarrassed about, but don’t worry — once the guys see your huge plate of food, your masculinity will once again be unquestioned:

Quite some time ago, Laura McD. sent us a link to an NPR story about a new ad campaign for baby carrots (which, if you didn’t know, aren’t actually immature carrots; they’re just regular carrots peeled and cut into small pieces). In an effort to appeal to teens, these ads openly satirize marketing tropes used to sell lots of snacks, especially the effort to market junk food as totally extreme! The website self-consciously makes the link to junk food, winking at the audience about the absurdity of EXTREEEEEME!!!!! marketing, yet hoping that rebranding carrots as similar to junk food, and using the marketing tactics they’re laughing at, actually increases sales. So, for instance, they have new packaging that looks like bags of chips:

The ads serve as a great primer on extreme food marketing cliches, complete with associations with violence (and stupidity), the sexualization of women, and the constant reminder via voiceovers and pounding music that this food is freakin’ extreme, ok?!?!

/p>

This one parodies ads that sexualize both women and food and present eating as an indulgence for women:

The ad campaign presents all this with a tongue-in-cheek tone of “isn’t this ridiculous?” But they’re also genuinely trying to rebrand a food product to increase sales, and clearly see the way to do that as downplaying any claims about health and instead using — if mockingly — the same marketing messages advertisers use to sell soda, chips, energy drinks, and other foods aimed at teens (particularly, though not only, teen boys).

As such, they provide a great summary of these marketing techniques and the jesting “Ha ha! We get it! We’re not like the other marketers who try to sell stuff to you! We know this is silly! (Please buy our product, though)” ironic marketing technique.

And now, I highly recommend you go watch the satire of energy drink commercials Lisa posted way back in 2007. It never gets old.