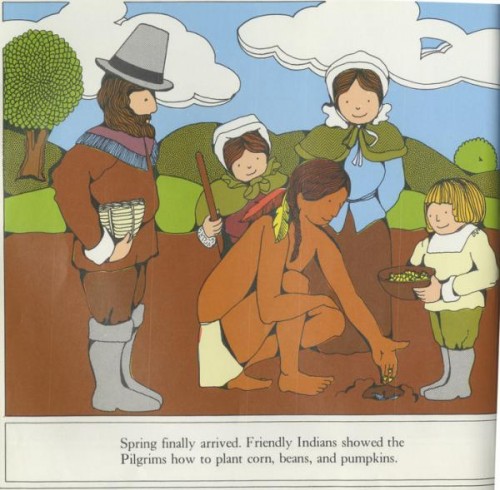

“They were coming to college believing that all Indians are dead,” said education professor Sarah Shear of her experience in the classroom.

Her students’ seeming ignorance to the fact that American Indians are a part of the contemporary U.S., not just the historical one, led her to take a closer look at what they were learning. She examined the academic standards for elementary and secondary school education in all 50 states, these are the guidelines that educators use to plan curricula and write textbooks. The results are summarized at Indian Country.

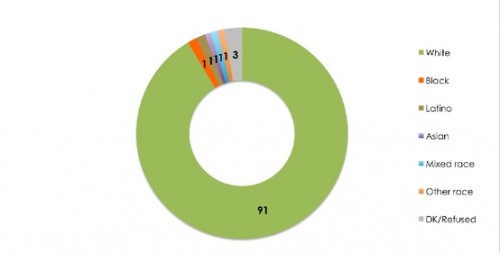

Shear found that the vast majority of references to American Indians — 87 percent — portrayed them as a population that existed only prior to 1900. There was “nothing,” she said, about contemporary issues for American Indian populations or the ongoing conflicts over land and water rights or sovereignty. Only one state, New Mexico, even mentions the name of a single member of the American Indian Movement.

Meanwhile, the genocidal war against American Indians is portrayed as an inevitable conflict that colonizers handled reasonably. “All of the states are teaching that there were civil ways to end problems,” she said, “and that the Indian problem was dealt with nicely.” Only one state, Washington, uses the word genocide. Only four states mention Indian boarding schools, institutions that represent the removal of children from their families and forced re-socialization into a Euro-American way of life.

The fact that so many people absorb the idea that Native Americans are a thing of the past — and a thing that we don’t have to feel too badly about — may help explain why they feel so comfortable dressing up like them on Halloween, throwing “Conquistabros and Navahos” parties, persisting in using Indian mascots, leaving their reservations off of Google maps, and failing to include them in our media. It might also explain why we expect Indian-themed art to always feature a pre-modern world.

Curricular choices matter. So long as young people learn to think of Indians no differently than they do Vikings and Ancient Romans, they will overwhelmingly fail to notice or care about ongoing interpersonal and institutional discrimination against American Indians who are here now.

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.