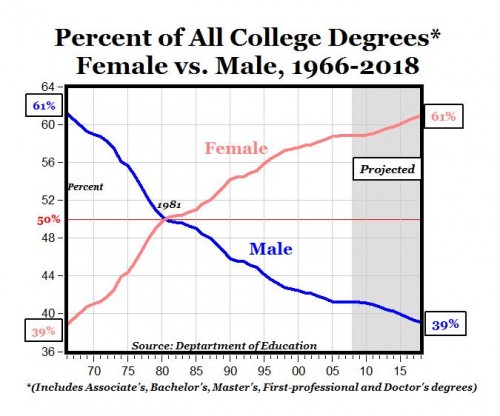

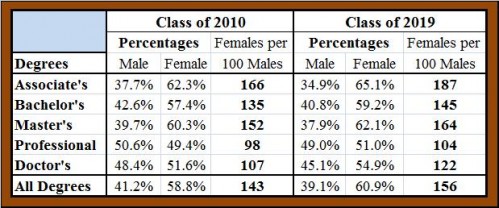

In this ten-minute talk, super-famous psychologist Philip Zimbardo talks about cultural differences in the perception and orientation towards time… and how that translates into boys dropping out of high school and underperforming in college. How does he make the link? Watch:

Via BoingBoing.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.