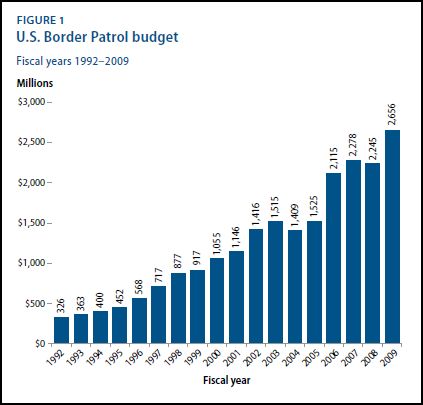

The Center for American Progress released a report detailing the state of border policing and the projected impact of immigration policies. First, notice that spending on border patrol and the number of border patrol agents in the southwest have increased significantly between 1992 and 2009:

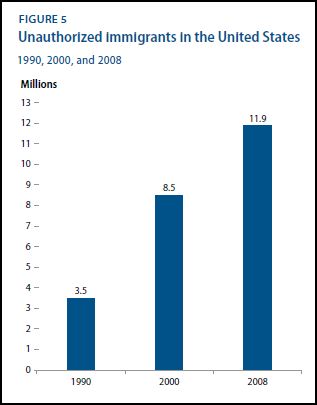

Still, despite this, the number of people illegally crossing the border has increased:

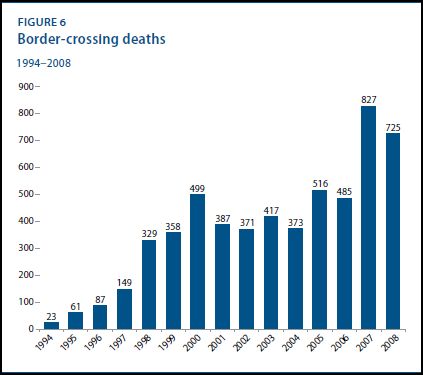

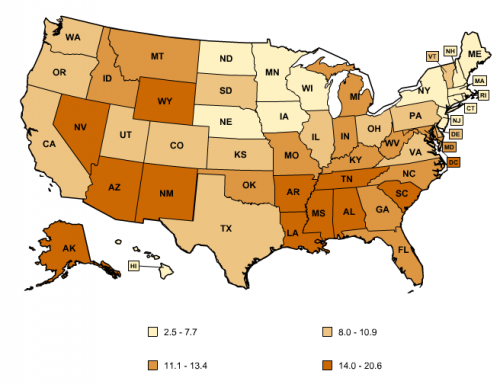

So the policing hasn’t deterred a rise in disallowed border crossings, but it has made it more dangerous:

So, the U.S. is spending a lot of money trying to keep undocumented non-citizens out. Is it worth it?

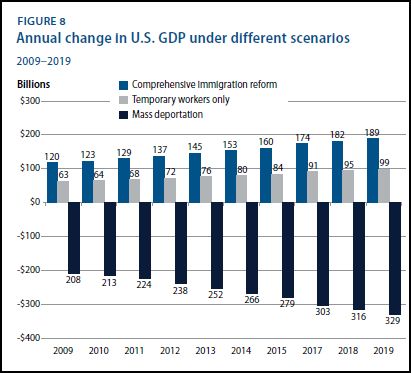

The report also discusses projected changes in the GDP under three different scenarios: immigration reform, allowing temporary workers only, and mass deportation.

The figure suggests that undocumented workers are making a substantial contribution to the well-being of the U.S. economy, one that would decrease under conditions of mass deportation. Temporary workers are helpful, but real immigration reform that would bring in greater numbers of permanent and temporary workers is the best thing for America.

Hat tip to Graphic Sociology.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.