Jeff H. sent in a link to a graphic at Civil Eats that lets you see the rise in U.S. daily caloric availability between 1970 and 2008, and where the additional calories are coming from. They are based on USDA data on food available for human consumption, minus what is wasted through being thrown out, spoiling before making it to the store, etc., to approximate average daily calorie consumption. It’s a rough measure, and clearly actual consumption will vary widely, but the overall changes provide some insights into the changing U.S. diet.

Note: I sometimes used the word “consumption,” “consumed,” etc., in the post since availability is an approximation of it, but as a reader pointed out, I should have been more careful, so I’ve fixed it throughout the post.

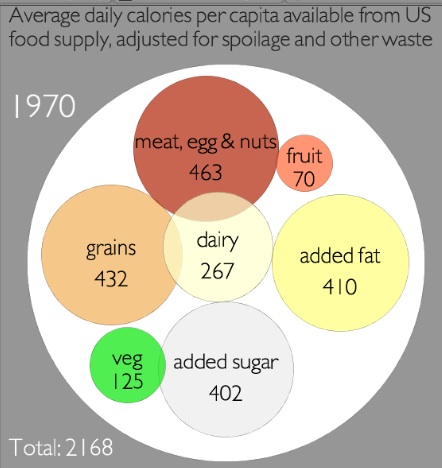

In 1970, we consumed had available an average of 2,168 calories per day, and the single largest source was meat/eggs/nuts:

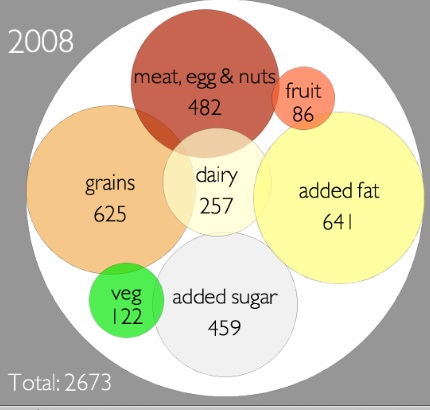

By 2008, we had 2,673 calories available on average. The big jumps were in added fat — there are 231 more calories a day available per person, and it’s now the single largest source of calories — and grains. I was surprised to see how small the increase in added sugars was…and calories available from vegetables and dairy actually went down:

Overall, that’s an increase in available calories of 23.3% during this 38-year time frame.

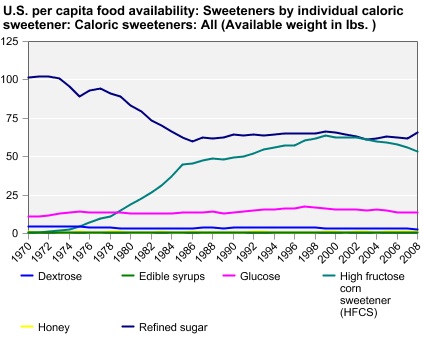

You can go to the Economic Research Service website and create charts or tables of caloric availability for specific food groups. For instance, the chart on changes in sweeteners shows the jump in use of high-fructose corn syrup, and an accompanying decrease in dextrose:

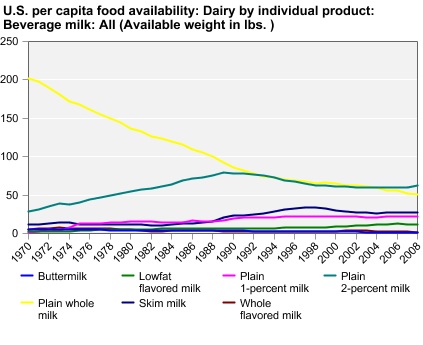

There’s a lot less whole milk than there used to be:

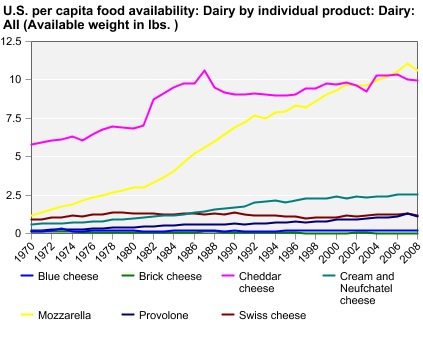

But we’ve grown to love mozzarella and make a lot more of it:

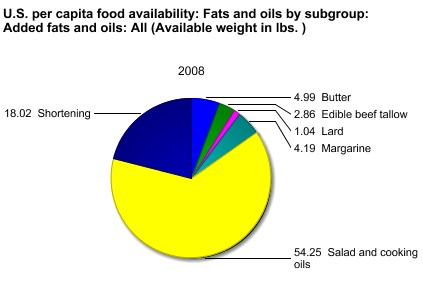

Or instead of looking at trends over time, you can get the breakdown for one particular year. Here are the sources of our added fats for 2008:

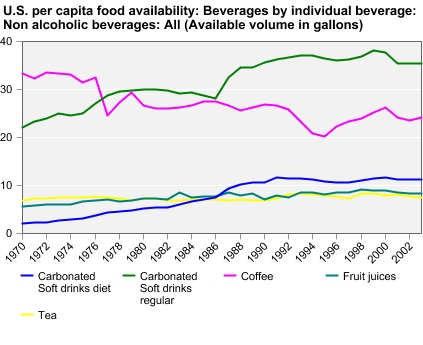

Non-alcoholic drinks (excluding milk):

I warn you, this is one of those things where it seems like you’ll just look for a second, and the next thing you know you’ve spent 45 minutes making customized charts of every possible category of food.

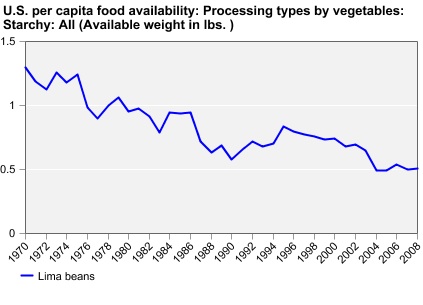

Also, we do not like lima beans:

UPDATE: Reader Chorda provides some context that I think is helpful:

The added fat looks impressive, but because fat has 9 calories per gram that increase ends up only being 25.6 grams of fat over the 1970 amount, or 0.903013 ounce. Yes, less than an ounce of fat can add 231 calories. On the other hand, the additional grains and sugar combined would be 62.51 grams of carbohydrates, or 2.20497 ounces dry weight and 250 new calories from carbohydrate sources.

Just over three ounces of food can make a difference of 481 calories. Eating that extra 3.1 ounces every day for a week is 3,367 calories. One pound of fat is equal to 3,500 calories.

Take two tablespoons of oil. Combine with three tablespoons flour and one tablespoon sugar. That is the largest difference between 1970 and 2008. Could you even get a single pancake out of that?