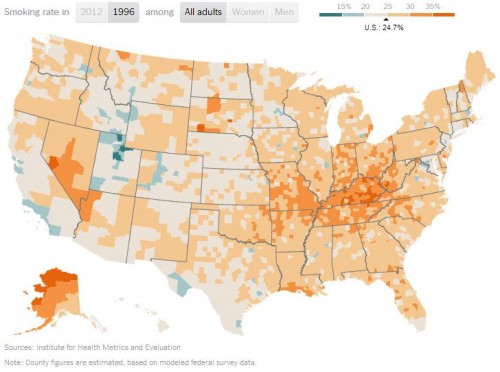

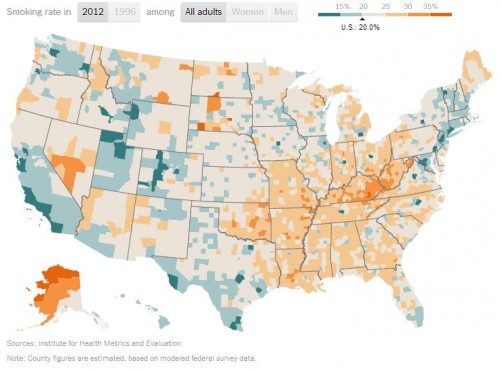

At the New York Times, Sabrina Tavernise and Robert Gebeloff discuss the tenaciousness of tobacco in low-income areas. Smoking rates are declining, but much more slowly in some counties than others. Local residents suggest that smoking is the least of their worries:

“Just sit and watch the parking lot for a day,” Mrs. Bowling said. “If smoking is the worst thing that’s happening, praise the Lord.”

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.