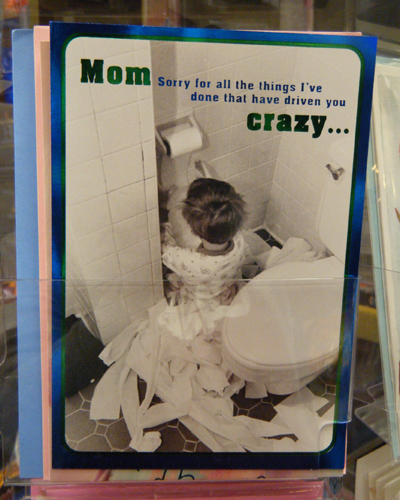

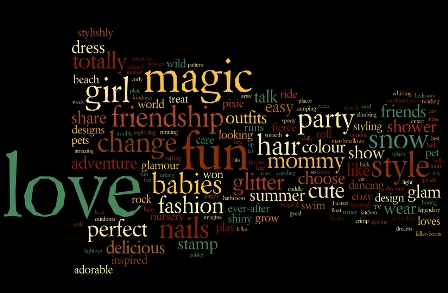

Christine B. sent along this Mother’s Day card:

It captures the normative idea that boys are naturally naughty (“I was just doing my job”). It also normalizes the notion that moms will be driven crazy by their sons, but accept their misbehavior as inevitable, even lovable.

(By the way, I know I can’t see the child’s face; it could be a girl. Reading the cues — short hair, blue and green colors — and the cultural context, I figure it’s supposed to be a boy.)

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.