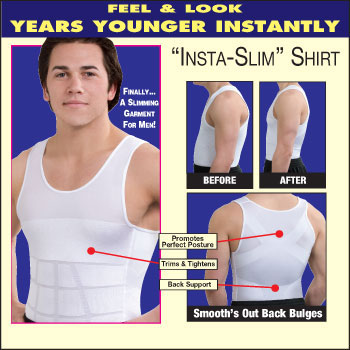

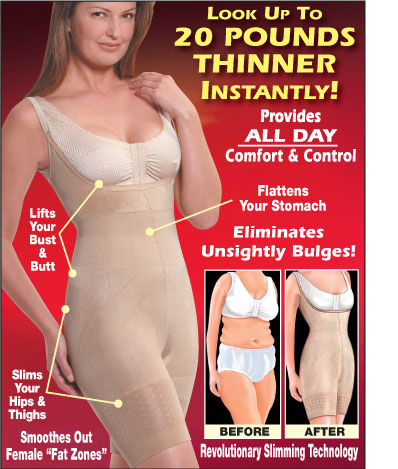

Elizabeth C. sent along two advertisements for body slimming garments from DreamProductsCatalog, one for men and one for women. Side-by-side, they reveal subtlety different expectations for male and female bodies:

Notice that the women’s garment is aimed solely at making her thinner and more fit appearing. It “slims,” “eliminates unsightly bulges,” “lifts,” and makes her look “20 pounds thinner.” Her sexy pose and come hither look emphasizes that her main job is to look good. In contrast, the man looks confidently and calmly into the camera and, while his garment is also aimed at making him look more “slim” and “trim,” it is also supposed to make him “feel” better and look younger. It improve his posture and offer back support, too.

The difference here is subtle, and I don’t mean to make too much of it, but it is nonetheless an illustration of the variety of uses to which men’s bodies are believed to be put (aesthetic, yes, but also functional and personal) and the one primary thing that women’s bodies are supposedly for (being looked at).

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.