Originally posted at Religion Bulletin.

Now that Denver has fallen out of the playoffs, I want to write an homage to a figure I, like so many others, find fascinating: Broncos quarterback Tim Tebow. Carter Turner over at Religion Dispatches has suggested that the “real reason” for “Tebow fever” was the theological investment that atheists and theists alike had in watching Tebow succeed or fail. I think that’s absolutely right: Tebow’s body became a sort of theological battleground for broader religious and cultural forces. But I also think there’s an even more elementary reason, one that becomes apparent when we think about Tebow not just as a proxy for doctrine, but as a particular religious body.

Feminism, poststructuralism, and decolonial studies in the humanities have made scholars more and more aware of the importance of bodies. Whereas the logocentric western tradition focused on words — the creations of the intellect — 21st century global scholarship sees words as a secondary function of embodiment. In religious studies, scholars such as Talal Asad, Kimerer LaMothe, and Saba Mahmood have called on us to explore how bodies, through practices, are constituted as religious subjects. Bodies become religious through performance, through embodied exercises that, through repetition, inscribe us with the modalities of a religious “ethics.” But embodiment is more than just practices. I here want to suggest a different direction for understanding the relationship between religion and bodies.

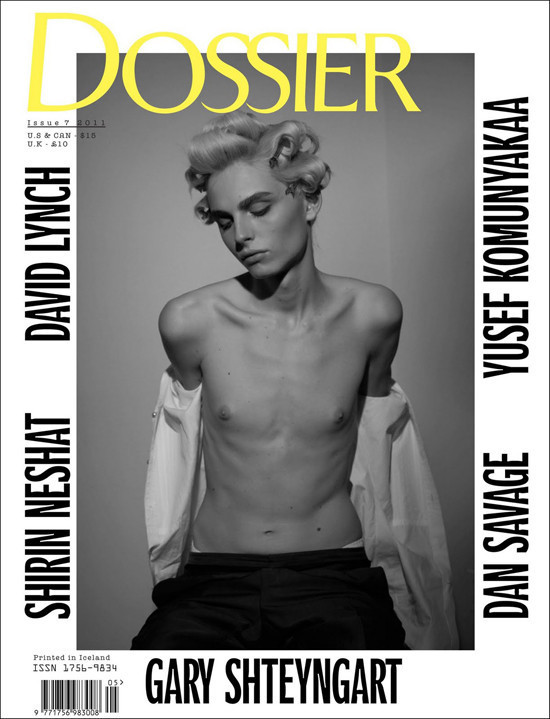

Here’s something I often ask my students to do: Look at this body. How does religion converge on this body?

Let me tell you what I see, using my own bodily practice, martial arts, as a lens. This is a body I would not want to fight. It’s not just about dense muscle lines, the sheer evidence of physical strength, reach, and an intricately arranged posing that suggests bodily self-awareness and sharp muscular intelligence. This body is compelling. It draws the eye. You want to watch it.

This is more dangerous than physical strength — the kind of strength you build on the bench press or the curl. It’s a “presence.” The kind of strength that stops bodies in their tracks without landing a punch. And the kind of strength that draws allies, that rewrites the broader bodily landscape on which conflict happens. This body has what we might call, following Max Weber, “charisma.”

This way of looking at bodies helps us think again about a fact that has become dramatically apparent in the past two years: Tebow is fascinating. People love to talk about him, love to love him, love to hate him. Tebow fever didn’t just happen. It was and is something is felt–viscerally–by millions of bodies around the world.

On the one hand, Tebow is a leader–an emblematic body — for millions of Christians who see in him a dignification of their faith. Faith here is not an abstract personal belief. It is an identity formation, an Us. Tebow is the champion of a certain Christian Us, an embodiment of values and a leader who rallies the believers. As a champion, he doesn’t win through debate, he wins through charisma. He is a hero, resplendent on the battlefield.

At the same time, Tebow is fascinating to other groups — to other bodies — that are frustrated with or skeptical of the Christian Us — and particularly the Christian Us that has managed to insinuate itself into the corridors of power in America through one (but only one) of its instantiations, the Christian Right, a major driver in contemporary Republican politics. These bodies, as Turner pointed out, are interested in Tebow’s failure, the fall of the enemy’s flag.

My argument, however, is this: this profile of the divergent responses to the nexus of religious and cultural forces that converge on the image of Tebow’s body would be irrelevant and unread if Tim Tebow were a schlub–a homely, uninteresting, modest body, the kind of body that bus drivers drive past at the bus stop. It is also an open question to me how we would be responding to Tebow if he were not a white body. Those who want to challenge Tebow, to fight Tebow, to talk about Tebow are drawn in by the seductions of this image–the power of Tebow’s body — no less than those who are so ardently admiring of Tebow that criticism of him becomes a political rallying cry. Tebow’s body is a magnetic body, a charismatic body. It bends other bodies towards it–in both positive and critical ways.

This, then, is one of the main ways that religion happens — how identities, beliefs, and affects form and fuse: not through the advance of doctrine, but through the magnetism of religious bodies.

Thanks to William Eric Pedersen for talking this post out with me and pointing me in the direction of the unanswered question on race.

————————

Donovan O. Schaefer is an adjunct instructor in the Department of Religious Studies at Le Moyne College. His interests involve the relationship between religion, bodies, and emotion. In his dissertation, Animal Religion: Evolution, Affect, and Radical Embodiment, he argues for understanding religion in terms of a set of affective bodily practices that are shared by human and non-human animals.

If you would like to write a post for Sociological Images, please see our Guidelines for Guest Bloggers.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.