The first nice weekend after a long, cold winter in the Twin Cities is serious business. A few years ago some local diners joined the celebration with a serious indulgence: the boozy milkshake.

When talking with a friend of mine from the Deep South about these milkshakes, she replied, “oh, a bushwhacker! We had those all the time in college.” This wasn’t the first time she had dropped southern slang that was new to me, so off to Google I went.

According to Merriam-Webster, “to bushwhack” means to attack suddenly and unexpectedly, as one would expect the alcohol in a milkshake to sneak up on you. The cocktail is a Nashville staple, but the origins trace back to the Virgin Islands in the 1970s.

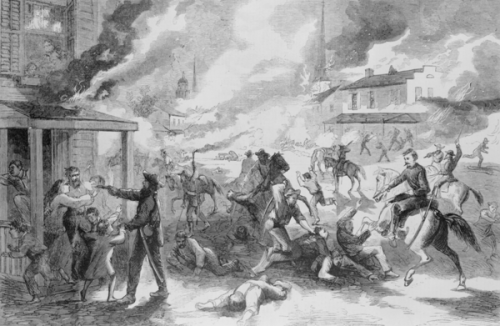

Here’s the part where the history takes a sordid turn: “Bushwhacker” was apparently also the nickname for guerrilla fighters in the Confederacy during the Civil War who would carry out attacks in rural areas (see, for example, the Lawrence Massacre). To be clear, I don’t know and don’t mean to suggest this had a direct influence in the naming of the cocktail. Still, the coincidence reminded me of the famous, and famously offensive, drinking reference to conflict in Northern Ireland.

When sociologists talk about concepts like “cultural appropriation,” we often jump to clear examples with a direct connection to inequality and oppression like racist halloween costumes or ripoff products—cases where it is pretty easy to look at the object in question and ask, “didn’t they think about this for more than thirty seconds?”

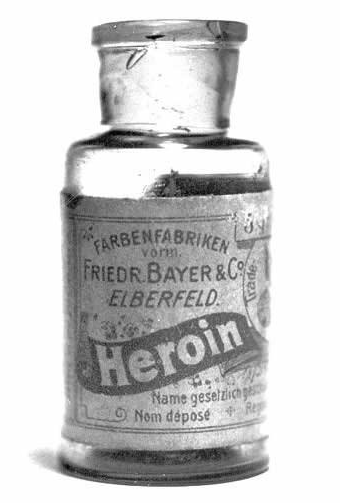

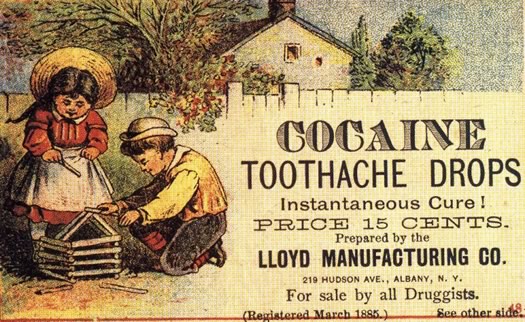

Cases like the bushwhacker raise different, more complicated questions about how societies remember history. Even if the cocktail today had nothing to do with the Confederacy, the weight of that history starts to haunt the name once you know it. I think many people would be put off by such playful references to modern insurgent groups like ISIS. Then again, as Joseph Gusfield shows, drinking is a morally charged activity in American society. It is interesting to see how the deviance of drinking dovetails with bawdy, irreverent, or offensive references to other historical and social events. Can you think of other drinks with similar sordid references? It’s not all sex on the beach!

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, on Twitter, or on BlueSky.