Last week I posted about some potential problems of “awareness branding,” when products are marketed by promising to make a donation to breast cancer research, or wilderness restoration, or something of the sort. Greg P. then sent me a link to a video on RSA Comment where economist/philosopher Slavoj Zizek argues against a reliance on private charity, and particularly ethical consumption, as a solution to global problems. He suggests that, say, buying fair-trade coffee at Starbucks is unlikely to relieve inequities that are directly related to global capitalism (of which Starbucks is a part and beneficiary), and may in fact reinforce them by making individuals in more privileged nations feel like they’ve done something to address the problem, thus relieving them of any obligation to look more deeply into the problem:

activism/social movements

Cross-posted at Ms.

Happy A. sent in an article at comment dit-on about a new anti-domestic violence ad in Chile that tells men not to hit women by using openly homophobic language — specifically saying that a man who hits a woman is a “maricón,” the equivalent of “faggot”:

Translation of the main text: “A faggot is one who hurts a woman.”

It’s a blatant example of the way leftist groups often undermine each other, fighting one form of inequality or discrimination by reinforcing another (see: everything PETA ever did). The group that put out the PSA added that a man who hits a woman is “poco hombre,” or barely a man, reinforcing the idea that gay men are insufficiently masculine. As the comment dit-on post author says, “Clearly, a larger conversation needs to take place about what it means to be powerful and attitudes that marginalize the powerless.”

UPDATE: Reader chinamorena says, “adding an interesting layer is the fact that the second man who speaks in the ad is Jordi Castell, a publicly gay tv personality.”

October is National Breast Cancer Awareness Month. Accordingly, during October we come across more than the normal number of pink-ribbon-adorned items that variously give a portion of proceeds to breast cancer research, remind women to conduct breast exams, contain supportive messages for breast cancer survivors, or just sort of, you know, support the existence of boobs and oppose cancer. For instance, Alicia, the moderator of Think Before You Pink, found this thong

And Renée Yoxon noticed that Staples, among other office-supply stores, has a lot of pink ribbon products for sale, including pink-ribbon paper, file folder, calculators, daily planners, pens, and, in Canada, a tape dispenser from 3M shaped like a high-heeled shoe:

We’ve posted on the whole issue of breast cancer awareness branding before. And one response that always comes up is, basically, yes, companies may be using breast cancer as a marketing tool to increase sales, but if by doing so they also donate money for breast cancer research or prevention, who cares? By buying pink-ribbon address labels, money goes to fight breast cancer that probably wouldn’t have been donated otherwise, so the net effect is good, right?

In his book Buying In: What We Buy and Who We Are, Rob Walker suggests perhaps not. He summarizes a number of studies that found that “doing good in one area of life provided a rationale to worry less about such things in another” (p. 222). Specifically, feeling they had contributed in some way (by imagining they had agreed to volunteer at a community organization) significantly increased subjects’ preference for “luxury” items. It appears that feeling we have done a good deed makes us feel like we deserve rewards in other arenas, or at least frees us to make decisions we might otherwise be a bit embarrassed about.

Walker connects this research to the wide array of companies that either create a particular product that is slightly more eco- or labor-friendly than their regular line or that donate a tiny portion of profits to a charity of some sort. He suggests that the ability to easily “do good” through consumption — that is, I can choose the pink-ribbon file folders and feel good about myself for being a good citizen — may contribute some money to a particular charity, but may ultimately lead us to be less concerned about the impacts of our other consumption choices. As Walker summarizes the effect,

These various efforts each add just enough options to the miles of retail shelves to give us all an ethical fix — to do our one good shopping deed. Then we can push our basket a little farther down the aisle, letting other rationales take over: Here’s a bargain, here’s a great product…and here, yes, here is something ethical. I’ll take one of those, too. (p. 223)

From this perspective, this type of branding may benefit companies not just by making it more likely we’ll buy the specific product they’ve attached a pink (or red, or yellow, or whatever color) ribbon to, but by satisfying our need to feel like we’re aware, concerned consumers, and thus making us less likely to question the production practices of the other items we’re choosing among.

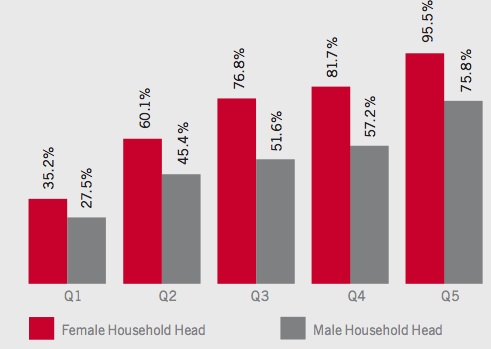

Emma M.H. sent us a link (via Jewish Philanthropy) to a study by the Center of Philanthropy, at Indiana University, about differences in financial donating by men and women. The report looks at data from a 2007 nationally representative survey of households, in which respondents were asked about their charitable giving in 2006. To isolate differences in giving, the report includes data only on single heads of household (whether never-married, divorced, or widowed), since in married households it’s difficult to distinguish who made the decision to donate (they point out that the literature is also very clear that married households are much more likely to donate than non-married households). You can get a copy of the actual questionnaire here.

They break the data down by income as well, dividing them into quintiles (that is, each category contains 20% of respondents). The income quintiles are: Q1 = $23,509 or less, Q2 = over $23,509 but less than $43,500, Q3 = over $43,500 but less than $67,532, Q4 = over $67,532 but less than $103,000, and Q5 = $103,000+.

As we see, in each income category non-married women were more likely to donate to charities of some sort:

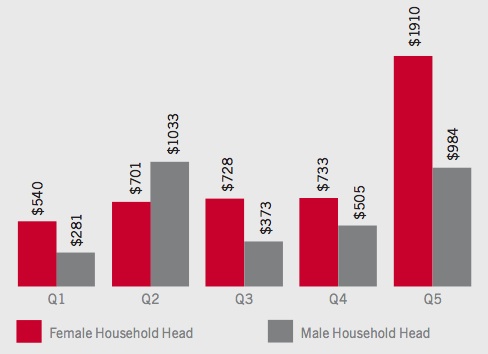

Women also generally gave more:

It’s interesting to me that the total amount of the giving doesn’t vary more by income for non-married women (the amount of reported giving is basically the same for the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quintiles), yet varies so much for non-married men. Thoughts on what’s going on there?

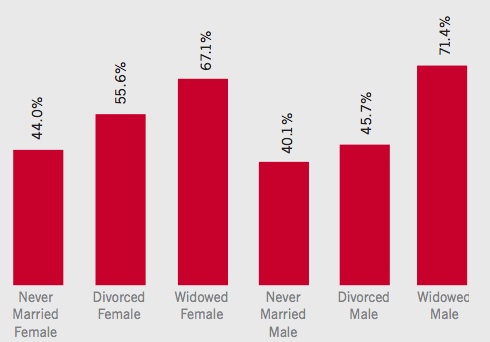

Likelihood of giving also varies quite a bit depending on type of single status — those who are widowed are quite a bit more likely to donate than the never-married, which is probably partially a factor of age and related factors like generally higher incomes/wealth:

As we’ve posted on in the past, women are also more likely to be involved in volunteer work.

I’d love to see a breakdown of where men and women donate, but the report didn’t provide that level of detail.

Breast cancer awareness campaigns have perfected the performance of social cause support. Wearing a pink ribbon, a pin with a pink ribbon, or something with a pink ribbon on it is now coterminous with concern and support for people diagnosed with breast cancer. Many companies now have breast cancer awareness-themed products.

Similarly, yellow ribbons with the phrase “support our troops,” most notably magnetized to car bumpers, is another form of “conspicuous cause endorsement.” Stephen W. discovered another example of this form of “activism,” this time in collaboration with Goodyear tires.

From what I can discern, the programconsists of putting “Support Our Troops” tires on Nascar cars sponsored by Goodyear, donating $20,000 towards troop-supporting causes, and then asking you to buy their tires and donate your own money.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Stephen W. sent in a photograph of a public relations notice at a gas station in Kansas City. The notice, from BP, explains that the owner of the BP gas station is a member of the community:

The notice is clearly an effort to smooth over the negative publicity BP has recieved as a result of the oil spill in the gulf. On the one hand, it seems obvious that it’s disingenuous for BP to claim that they are “part of the community.” And, if one wants to boycott BP, one would not want to buy at a BP station.

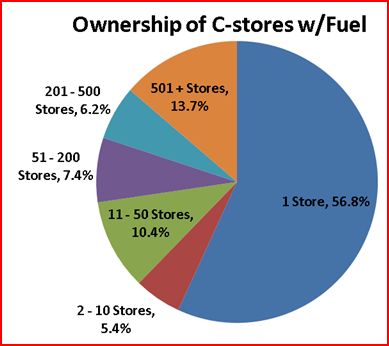

On the other hand, BP is right. According to the National Association for Convenience Stores, 80% of the gas in the U.S. is bought at convenience stores and in only 2% of cases are these owned by major oil companies (the remainder is largely sold through superstores like Costco and Sam’s Club). 57% of the time, these stores are owned by a person for whom it is a small business and it is the only convenience store they own.

So it is true that, in almost all cases, attempting to police or punish BP by refusing to buy their gas is also hurting a small business owner who has zero control over BP and its policies.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

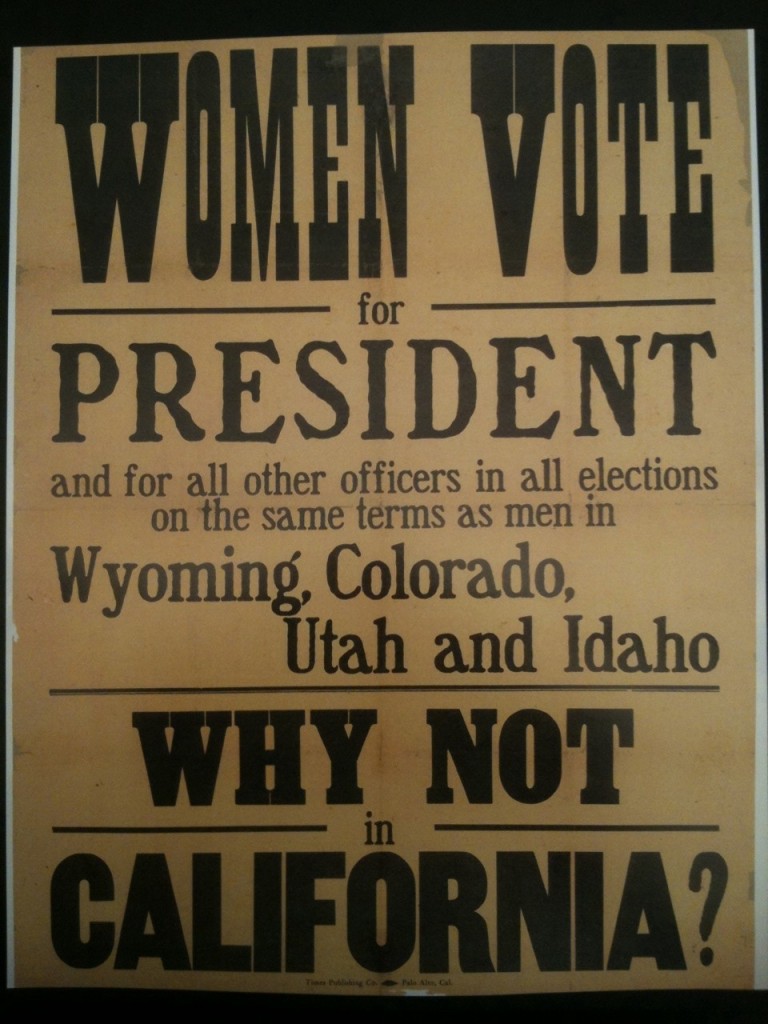

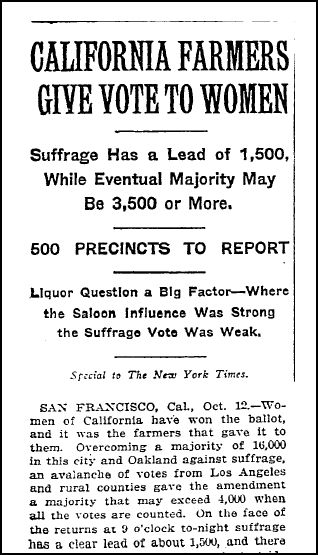

On this day in 1911, suffragettes in California squeaked out a victory, making the state the sixth to give women the vote and doubling the number of female voters in the U.S. See David Dismore’s great summary at Ms.

Campaign poster reproduction (c. 1896-1910, from David Dismore’s collection):

The New York Times reports:

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

This 8-minute video from Powering A Nation documents the fight of Kindra Arnesen to save her family and her Gulf Shores community. It’s a stirring portrait of how one family has been affected by the oil spill and is trying to fight back:

Via NPR.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Cross-posted at Ms.

Happy A. sent in an article at comment dit-on about a new anti-domestic violence ad in Chile that tells men not to hit women by using openly homophobic language — specifically saying that a man who hits a woman is a “maricón,” the equivalent of “faggot”:

Translation of the main text: “A faggot is one who hurts a woman.”

It’s a blatant example of the way leftist groups often undermine each other, fighting one form of inequality or discrimination by reinforcing another (see: everything PETA ever did). The group that put out the PSA added that a man who hits a woman is “poco hombre,” or barely a man, reinforcing the idea that gay men are insufficiently masculine. As the comment dit-on post author says, “Clearly, a larger conversation needs to take place about what it means to be powerful and attitudes that marginalize the powerless.”

UPDATE: Reader chinamorena says, “adding an interesting layer is the fact that the second man who speaks in the ad is Jordi Castell, a publicly gay tv personality.”

October is National Breast Cancer Awareness Month. Accordingly, during October we come across more than the normal number of pink-ribbon-adorned items that variously give a portion of proceeds to breast cancer research, remind women to conduct breast exams, contain supportive messages for breast cancer survivors, or just sort of, you know, support the existence of boobs and oppose cancer. For instance, Alicia, the moderator of Think Before You Pink, found this thong

And Renée Yoxon noticed that Staples, among other office-supply stores, has a lot of pink ribbon products for sale, including pink-ribbon paper, file folder, calculators, daily planners, pens, and, in Canada, a tape dispenser from 3M shaped like a high-heeled shoe:

We’ve posted on the whole issue of breast cancer awareness branding before. And one response that always comes up is, basically, yes, companies may be using breast cancer as a marketing tool to increase sales, but if by doing so they also donate money for breast cancer research or prevention, who cares? By buying pink-ribbon address labels, money goes to fight breast cancer that probably wouldn’t have been donated otherwise, so the net effect is good, right?

In his book Buying In: What We Buy and Who We Are, Rob Walker suggests perhaps not. He summarizes a number of studies that found that “doing good in one area of life provided a rationale to worry less about such things in another” (p. 222). Specifically, feeling they had contributed in some way (by imagining they had agreed to volunteer at a community organization) significantly increased subjects’ preference for “luxury” items. It appears that feeling we have done a good deed makes us feel like we deserve rewards in other arenas, or at least frees us to make decisions we might otherwise be a bit embarrassed about.

Walker connects this research to the wide array of companies that either create a particular product that is slightly more eco- or labor-friendly than their regular line or that donate a tiny portion of profits to a charity of some sort. He suggests that the ability to easily “do good” through consumption — that is, I can choose the pink-ribbon file folders and feel good about myself for being a good citizen — may contribute some money to a particular charity, but may ultimately lead us to be less concerned about the impacts of our other consumption choices. As Walker summarizes the effect,

These various efforts each add just enough options to the miles of retail shelves to give us all an ethical fix — to do our one good shopping deed. Then we can push our basket a little farther down the aisle, letting other rationales take over: Here’s a bargain, here’s a great product…and here, yes, here is something ethical. I’ll take one of those, too. (p. 223)

From this perspective, this type of branding may benefit companies not just by making it more likely we’ll buy the specific product they’ve attached a pink (or red, or yellow, or whatever color) ribbon to, but by satisfying our need to feel like we’re aware, concerned consumers, and thus making us less likely to question the production practices of the other items we’re choosing among.

Emma M.H. sent us a link (via Jewish Philanthropy) to a study by the Center of Philanthropy, at Indiana University, about differences in financial donating by men and women. The report looks at data from a 2007 nationally representative survey of households, in which respondents were asked about their charitable giving in 2006. To isolate differences in giving, the report includes data only on single heads of household (whether never-married, divorced, or widowed), since in married households it’s difficult to distinguish who made the decision to donate (they point out that the literature is also very clear that married households are much more likely to donate than non-married households). You can get a copy of the actual questionnaire here.

They break the data down by income as well, dividing them into quintiles (that is, each category contains 20% of respondents). The income quintiles are: Q1 = $23,509 or less, Q2 = over $23,509 but less than $43,500, Q3 = over $43,500 but less than $67,532, Q4 = over $67,532 but less than $103,000, and Q5 = $103,000+.

As we see, in each income category non-married women were more likely to donate to charities of some sort:

Women also generally gave more:

It’s interesting to me that the total amount of the giving doesn’t vary more by income for non-married women (the amount of reported giving is basically the same for the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quintiles), yet varies so much for non-married men. Thoughts on what’s going on there?

Likelihood of giving also varies quite a bit depending on type of single status — those who are widowed are quite a bit more likely to donate than the never-married, which is probably partially a factor of age and related factors like generally higher incomes/wealth:

As we’ve posted on in the past, women are also more likely to be involved in volunteer work.

I’d love to see a breakdown of where men and women donate, but the report didn’t provide that level of detail.

Breast cancer awareness campaigns have perfected the performance of social cause support. Wearing a pink ribbon, a pin with a pink ribbon, or something with a pink ribbon on it is now coterminous with concern and support for people diagnosed with breast cancer. Many companies now have breast cancer awareness-themed products.

Similarly, yellow ribbons with the phrase “support our troops,” most notably magnetized to car bumpers, is another form of “conspicuous cause endorsement.” Stephen W. discovered another example of this form of “activism,” this time in collaboration with Goodyear tires.

From what I can discern, the programconsists of putting “Support Our Troops” tires on Nascar cars sponsored by Goodyear, donating $20,000 towards troop-supporting causes, and then asking you to buy their tires and donate your own money.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Stephen W. sent in a photograph of a public relations notice at a gas station in Kansas City. The notice, from BP, explains that the owner of the BP gas station is a member of the community:

The notice is clearly an effort to smooth over the negative publicity BP has recieved as a result of the oil spill in the gulf. On the one hand, it seems obvious that it’s disingenuous for BP to claim that they are “part of the community.” And, if one wants to boycott BP, one would not want to buy at a BP station.

On the other hand, BP is right. According to the National Association for Convenience Stores, 80% of the gas in the U.S. is bought at convenience stores and in only 2% of cases are these owned by major oil companies (the remainder is largely sold through superstores like Costco and Sam’s Club). 57% of the time, these stores are owned by a person for whom it is a small business and it is the only convenience store they own.

So it is true that, in almost all cases, attempting to police or punish BP by refusing to buy their gas is also hurting a small business owner who has zero control over BP and its policies.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

On this day in 1911, suffragettes in California squeaked out a victory, making the state the sixth to give women the vote and doubling the number of female voters in the U.S. See David Dismore’s great summary at Ms.

Campaign poster reproduction (c. 1896-1910, from David Dismore’s collection):

The New York Times reports:

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

This 8-minute video from Powering A Nation documents the fight of Kindra Arnesen to save her family and her Gulf Shores community. It’s a stirring portrait of how one family has been affected by the oil spill and is trying to fight back:

Via NPR.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.