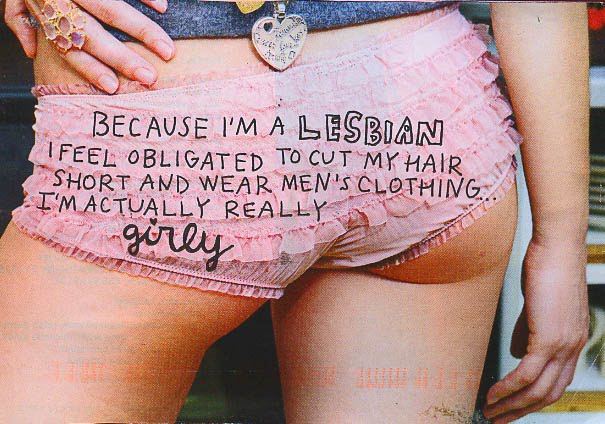

Suzy S. sent in an illuminating confession from PostSecret in which a woman confesses to being girly, but feels like she has to look more masculine because she’s a lesbian. It reads: “Because I’m a LESBIAN I feel obligated to cut my hair short and wear men’s clothing… I’m actually really girly”:

This woman says she feel “obligated” to tone down her girliness. In fact, adopting a masculinized appearance is one way that women signal to other people that they are gay, something they need to do because heterosexuality is normative and, therefore, generally assumed of everyone in the absence of signs otherwise. There are lots of reasons why lesbians may want to be visible.

They may want to be a symbol of the very existence of gay people and thereby fight the assumption that everyone is straight. They may want to find other gay women with which to build community or to find a girlfriend. Or they may simply want to ward off the unwanted attention of men. The style choices made by lesbians, then, aren’t simply about fashion or some internal inclination towards the masculine, as our confessor neatly illustrates. In some cases, at least a little bit, they’re strategic communication.

Related, see our fun post titled Revisioning Aspirational Hair.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.