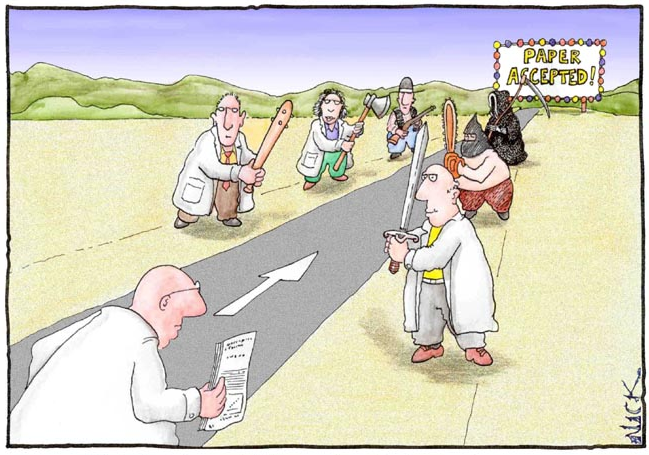

If you’re not (or not yet) an academic, this cartoon may not make much sense to you. But if you are…

(cartoon by Nearing Zero; via Philip Cohen)

(cartoon by Nearing Zero; via Philip Cohen)

For the uninitiated:

To get a paper published in an academic journal, scholars have to submit a draft to a journal and wait up to a year for feedback that is, not-uncommonly, rather brutal. This is because writing a journal article is difficult and our colleagues are rather smart. And busy. So there’s no time for hand-holding.

Decisions are usually “reject” (we never want to see this paper again as long as we live) or “revise-and-resubmit” (right now this paper sucks, but if you spend another six months of your life working on it, there is some possibility that we might publish it… maybe… but for now it’s important that you understand that it really sucks).

It’s typical to have to submit a paper to two or three journals before it’s finally accepted. And it’s not unheard of to have to submit it to five or six. So… yeah, it can feel like being beaten, repeatedly. For sure.

I’ll take harrowing publication stories in the comments, if you’ve got ’em!

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.