The World Health Organization (WHO) defines neurological disorders as physical diseases of the nervous system and psychiatric illnesses as disorders that manifest as abnormalities of thought, feeling, or behaviour. In fact, however, there are longstanding unresolved debates on the exact relationship between neurology and psychiatry, including whether there can be any clear division between the two fields.

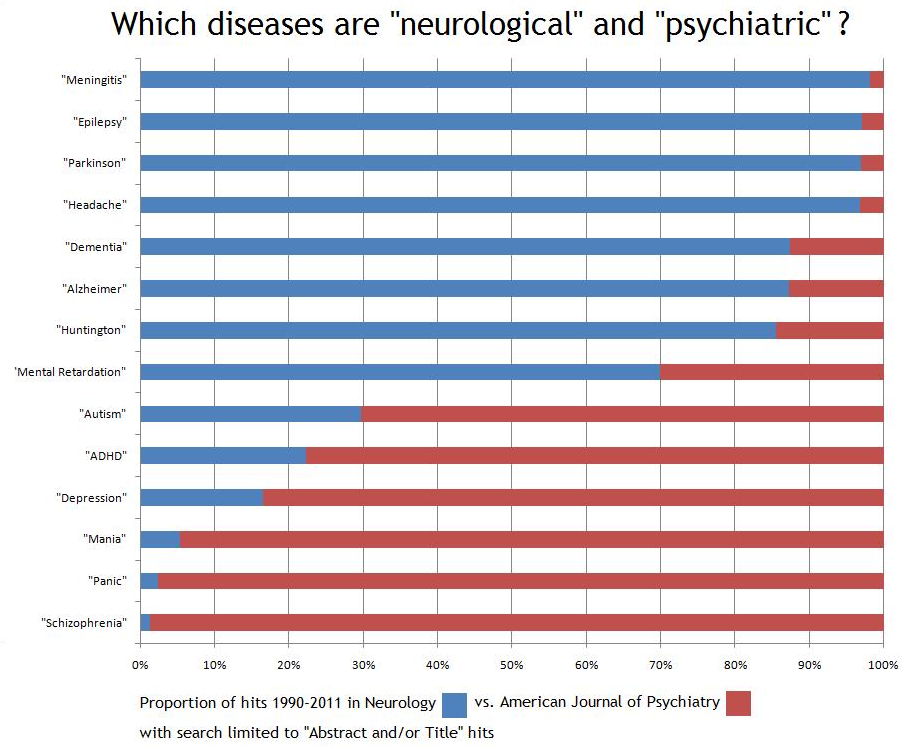

Related to this, Brandy B. sent us a figure from the blog Neuroskeptic graphing the proportion of journal articles on various disorders included in The American Journal of Psychiatry versus the journal Neurology over the past 20 years. The image is interesting from a sociological standpoint in that, as Brandy writes, “it says far more about the sociology of these fields than about which disorders can be considered neurological or psychiatric.”

While debates regarding the neurological roots of psychiatric illnesses such as depression and schizophrenia are far from settled, the graph shows that the two disciplines have maintained varying levels of intellectual authority over different disorders. Some fall clearly into one domain or the other, while others are covered in both. Depression, for example, receives more attention than mania in Neurology, despite the fact that mania often occurs alongside depression as a symptom of bipolar disorder.

The information in this graph serves as a reminder that what gets published in academic journals, and the topics over which disciplines exercise authority, are the results of social processes. Disciplines are artificial categories of knowledge, solidified through the creation of institutional structures like university departments, degree programs, and academic journals. Psychiatry, for example, didn’t emerge as a discipline until the 19th century; this emergence was rooted in a social context in Western Europe where rising numbers of people were being institutionalized and attitudes regarding the treatment of mental illness were changing. By claiming membership in disciplines based on common academic backgrounds, research methodologies, and topics of study, scholars contribute to the reproduction of these disciplinary boundaries.

The peer-review process is one facet of this social reproduction of disciplinary boundaries that is particularly relevant to the image above. Research and papers that are submitted, accepted, and funded must appeal to reviewers and conform to the criteria set out by the journal or discipline within which researchers wish to publish. In the case of neurology and psychiatry, it appears based on this graph that the peer-review process may uphold disciplinary boundaries, as reviewers for each discipline’s journal appear to favour articles on certain disorders.

The divisions between neurology and psychiatry suggested in the image above stir up lots of interesting questions not only about what we consider to be “neurological” or “psychiatric”, but more generally about the social production of knowledge.

——————————

Hayley Price has a background in sociology, international development studies, and education. She recently completed her Masters degree in Sociology and Equity Studies in Education at the University of Toronto.

If you would like to write a post for Sociological Images, please see our Guidelines for Guest Bloggers.

Comments 25

AK — September 9, 2011

Great post. I have a personal example that illustrates the hazy boundary between neurological (physical) and psychological (mental, or personality) characteristics. My 3 year old son has low muscle strength and poor coordination. He also seems to have low motivation, is reluctant to try new physical activities, and is more "mellow" than a lot of kids his age. It's actually a pretty common condition called hypotonia. Doctors say that is a neuromuscular condition, with no known cause. But if he works hard, he gets stronger, gains better coordination, and can be "normal." But his "personality" makes him reluctant to push hard, physically.

So what is going on here? Physical problem? Psychological problem? The wikipedia page for this condition says that kids with hypotonia tend to be passive observers of physical activity and have low motivation to overcome obstacles - so this is not unique to my kid. What people typically say to explain this is that frustration early in life makes kids reluctant to try things that are hard.

I think it is a really interesting example of how "disorders" about which we have almost no understanding get categorized. In this case, it is labeled a neuromuscular condition, and the "personality" issues associated with it are basically ignored by doctors. But I can easily imagine the opposite being the case in another context. The child would be diagnosed with a personality disorder, and the physical dimension would be treated as secondary.

Becca H. — September 9, 2011

I must be missing the point somehow. I don't disagree that certainly scientific and academic disciplines in general are examples of social institutions, that the particular ways we identify "disordered" symptoms are thereby related to said social institutions, etc etc. But I just don't see how in the world a graph of the hits on names of disorders in these respective

journals "says far more about the sociology of these fields than about

which disorders can be considered neurological or psychiatric," *especially* if we're taking "neurological" or "psychiatric" to be a function of the aforementioned social institutions. What conclusion am I supposed to be drawing about the sociology of these fields? What are the "interesting questions" about the social production of knowledge that I'm just supposed to somehow wink-wink-nudge-nudge know about at the end of this article?

I don't think anyone -- or at least not anyone who spends any time thinking about it -- is going to say that the current state of neurological and psychiatric research is exactly representative of what is "natural" to human beings, or something like that. It's an ongoing social endeavor, just like pretty much any research program. But it's not as if there isn't a difference between what "neurology" and "psychiatry" are; it's not as if we should somehow be surprised, or as if there's somehow something telling, about the fact that neurologists will talk more about Parkinson's while psychiatrists will talk more about mania. So yes, I'm not sure what exactly the point of the above was -- I'm sure that the author is claiming there's a point, but it's certainly not explicitly stated anywhere...

Becca H — September 9, 2011

Also, I'd like to add -- this sentence really irked me: "Depression, for example, receives more attention than mania in Neurology, despite the fact that mania often occurs alongside depression as a symptom of bipolar disorder."

Of course depression would receive more attention than mania pretty much anywhere -- depression occurs with mania *and* without mania, so you'll be talking about it whether you're doing an article on any of the varieties of depression or bipolar disorder. What's this "despite the fact" business? Are we supposed to be annoyed on behalf of "mania" that it's not getting the attention it wants?

Maeghan — September 9, 2011

I think the problem is that disorders that are psychiatric are often also neurological. Mental illnesses are like other illnesses. They have to come from somewhere.

As a side note, I really don't think most people consider autism a "psychiatric disease." I also have issues with the word disease used in the context of a lot of these disorders.

Kimberley Marie — September 10, 2011

My emotional outbursts and derealisation were diagnosed as epilepsy because of an abnormal EEG - however, that turned out to be a misdiagnosis and what is more likely is that I have a combined anxiety/depression disorder. The medical response I receive is very different when I presented with having a neurological disorder versus now, when I present with a psychiatric disorder. When I had a neurological disorder, doctors were more receptive to my symptoms of fatigue and stress as being part of my illness, whereas now that these symptoms are psychiatric, I am increasingly being told that my fatigue and stress are part of a 'chosen lifestyle' (working a 40 hour week is a 'chosen' lifestyle, is it?) and I should deal with them and stop whinging.

Even better, my first neurologist initially called me eccentric and derided my emotional outbursts and feelings of dissociation as being part of some teenage angst. He changed his tune after the abnormal EEG, but as his diagnosis leading from that EEG turned out to be incorrect, I wonder at his attitude towards psychiatric illnesses.

Mick Bramham — September 12, 2011

I agree, psychiatry and neurology are often confused. Until 1948 the combined speciality of ‘neuropsychiatry’ was divided into ‘neurology’ and ‘psychiatry’. Neurology deals with numerous organic and physical diseases of the brain – such as Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia, Parkinson’s and Huntingdon’s disease. Psychiatry deals with emotional and behavioural problems. Without in any way wishing to minimise the suffering of those concerned, labels such as ADHD, depression, schizophrenia etc are descriptive labels as, contrary to popular understanding, there are no conclusive studies showing that they are brain diseases. If I may quote a psychiatrist here - the academic psychiatrist Dr Joanne Moncrieff states in her book “The Myth of the Chemical Cure” that “there is no established specific physical basis to psychiatric disorders”. Mick at www.wessextherapy.co.uk

Weekly Link Roundup – Pan Social Science Edition « A (Budding) Sociologist’s Commonplace Book — September 18, 2011

[...] Neurology vs. Psychiatry (via SocImages). As usual, Soc Images finds a fascinating graph that brings up as many questions as answers. In this case, the image shows the proportion of hits for different mental disorders that appear in psychiatry vs. neurology journals. [...]

Weekly List Bookmarks (weekly) | Eccentric Eclectica @ ToddSuomela.com — October 23, 2011

[...] Neurology vs. Psychiatry: The Social Production of Knowledge » Sociological Images [...]

Jafar_james — October 9, 2012

I am not a Doctor. My understanding is this. Neurology relates to the material and physical state of the brain while psychiatry deal with the mentality and metaphysical (something non-physical or beyond physical) state of the mind. You see a neurologist if the brain is a problem, and only psychiatrist if you are troubling yourselves with the mind.

Quick read on the sociology of….epistemology? | Interesting world — January 20, 2014

[…] http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2011/09/09/neurology-vs-psychiatry-the-social-production-of-kno… […]

Connections: the core of ‘thinking’ – Deep Brain Stimulation | N — allround & all around — March 31, 2014

[…] one big grey continuous spectrum, but for some clarification/discussion I would like to refer you here) result from an imbalance in these connections. Over the past three decades scientists have been […]

Zlar Vixen — April 18, 2020

Most neurologists have no interest in dealing with depression, nor other issues such as ADHD. Tics definitely fall within their scope of treatment, however, and I feel that autism will become an issue merely dealt by neurologists in the coming years. Psychiatry will quickly become replaced by advances in brain imaging techniques as well as neuroscience publications, and psychology, as usual, will keep its well-deserved spot in society as nothing more than a pseudoscience for "doctors" incapable of getting into medical school.