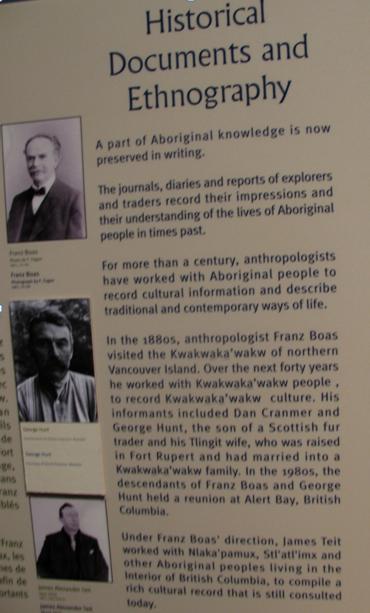

A recent Soc Images post on cultural appropriation highlighted issues of control over the production and representation of images of Indigenous peoples. On a related note, an image I captured during a recent visit to the Canadian Museum of Civilization (or as one of my professors has called it, the “Canadian Museum of Colonization”) highlights similar issues regarding the representation of Indigenous knowledges. This poster was displayed in the “First Peoples’ Hall” of the museum in a section dedicated to “Ways of Knowing”:

Two points are particularly striking. Firstly, the poster portrays the “preservation” of Indigenous knowledges as a project of colonizers and non-Indigenous anthropologists. Rather than attributing control over the production and representation of Indigenous knowledges to Indigenous peoples themselves, the poster depicts colonial “explorers” and anthropologists as the primary agents in these endeavors. Indigenous peoples themselves are merely portrayed as informants, leaving interpretation and presentation to colonizers and anthropologists. In recent years, numerous Indigenous scholars have written about the oppressive nature of this type of approach to Indigenous peoples and knowledges, pointing out how academic disciplines such as anthropology have been essential tools in the study and subjugation of Indigenous peoples as “primitive Others.”

Secondly, the poster presents Indigenous knowledges as static and unchanging, ignoring their dynamic nature and the ongoing experiences of Canada’s Indigenous communities. Canadian Indigenous scholar Andrea Smith* has argued that in settler societies such as Canada, false notions of the disappearance or threat of extinction of Indigenous peoples and their knowledges are at the foundation of cultural imaginations and serve as justifications for the appropriation of Indigenous lands and cultures. In this case, the threat of extinction is implied in the need for Indigenous knowledges to be “preserved in writing.”

This poster provides an entry point for questioning power relations inherent in the production and presentation of knowledge at the Canadian Museum of Civilization and similar institutions. This example demonstrates how the museum portrays a particular view of Canada and its relationship with Indigenous communities, one which ignores the historical and continuing reality of colonialism and its implications.

* Smith, A. (2006). Heteropatriarchy and the three pillars of white supremacy: Rethinking women of color organizing. In A. Smith (Ed.), Color of Violence: The Incite! Anthology (66-73). Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

—————————

Hayley Price has a background in sociology, international development studies, and education. She recently completed her Masters degree in Sociology and Equity Studies in Education at the University of Toronto with a thesis on Indigenous knowledges in development studies.

If you would like to write a post for Sociological Images, please see our Guidelines for Guest Bloggers.