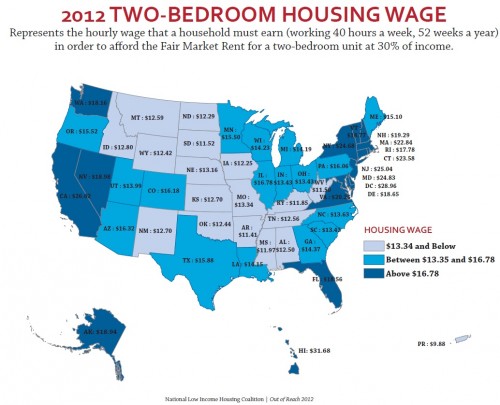

Each year the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) calculates the fair market rents for apartments throughout the U.S. in order to set standards for housing assistance payments and vouchers for Section 8. Using data from the Census and the American Community Surveys, HUD figures out the average cost for various sizes of apartments. You can easily look up data for fiscal year 2012 here.

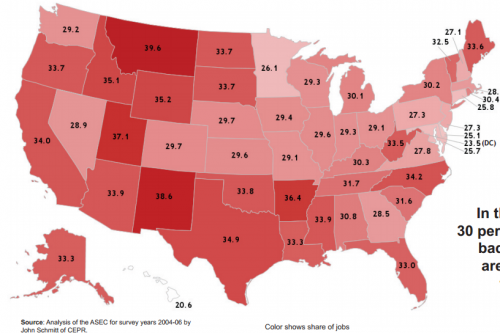

The generally-accepted standard for affordable, sustainable housing costs is that they should be about a third of a household’s income. The National Low Income Housing Coalition recently released a report on the mismatch between minimum wage — currently set at $7.25 nationally, with some states and municipalities having higher minimum wages within their boundaries — and the standard of living. The NLIHC report included this map showing the hourly wage that would be required for the HUD-calculated fair market rent to be about 30% of a full-time worker’s income:

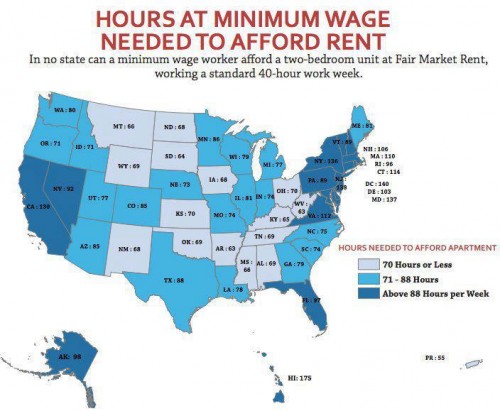

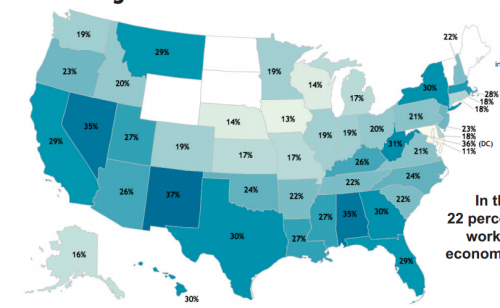

In no state does the minimum wage pay enough to hit the 30%-of-income standard of affordable housing costs. How many hours would a minimum-wage worker need to work per week to make enough that the fair market rent would be about a third of their income? A lot, from a low of 63 hours a week in West Virginia to a high of 175 in Hawaii:

Thanks to Dmitriy T.M. for the tip!