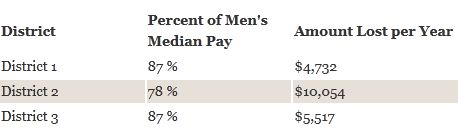

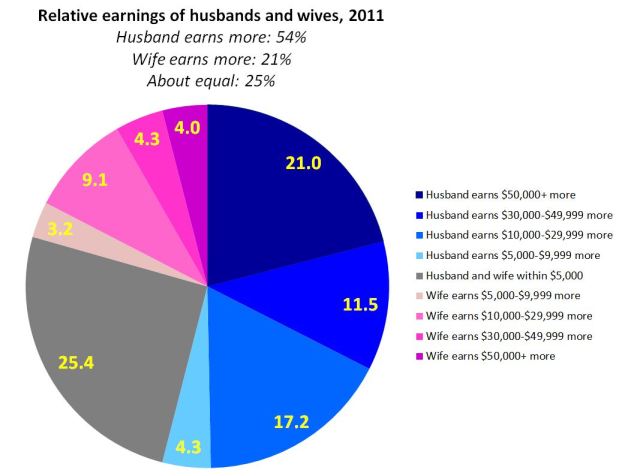

The National Partnership for Women & Families has posted an interactive map that displays the gender pay gap in each state and in the Congressional districts within the state. It uses Census Bureau data comparing full-time, year-round workers (that is, the scenario in which we’d expect women’s income to be closest to men’s). When you click on any state, it brings up information about it. For instance, in Nevada, women make 85% of what men do. Women working full-time have a median income of $35,484, while men’s median income is $41,803. The gap is smallest in the 1st and 3rd districts (both including parts of the greater Vegas metro area), but significantly larger in District 2, which covers the rest of the state, much of it rural:

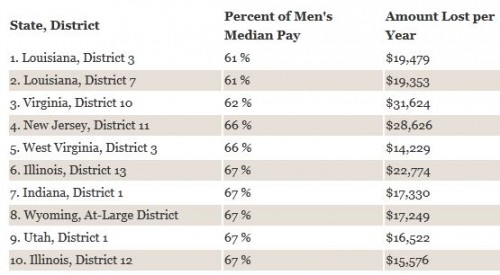

Here are the 10 U.S. Congressional districts with the largest gender gap in median pay:

They don’t list the state or districts with the smallest gap. Just from casually and non-systematically clicking around, the state with the most parity that I found was in Washington D.C., where women make 90% as much as men. Let us know in the comments if you find anywhere with an even smaller gap.