Cross-posted at Family Inequality and The Atlantic.

The problem of income inequality often gets forgotten in conversations about biological clocks.

The dilemma that couples face as they consider having children at older ages is worth dwelling on, and I wouldn’t take that away from Judith Shulevitz’s essay in the New Republic, “How Older Parenthood Will Upend American Society,” which has sparked commentary from Katie Roiphe, Hanna Rosin, Ross Douthat, and Parade, among many others.

The story is an old one — about the health risks of older parenting and the implications of falling fertility rates for an aging population — even though some of the facts are new. But two points need more attention. First, the overall consequences of the trend toward older parenting are on balance positive, both for women’s equality and for children’s health. And second, social-class inequality is a pressing — and growing — problem in children’s health, and one that is too easily lost in the biological-clock debate.

Older mothers

First, we need to distinguish between the average age of birth parents on the one hand versus the number born at advanced parental ages on the other. As Shulevitz notes, the average age of a first-time mother in the U.S. is now 25. Health-wise, assuming she births the rest of her (small) brood before about age 35, that’s perfect.

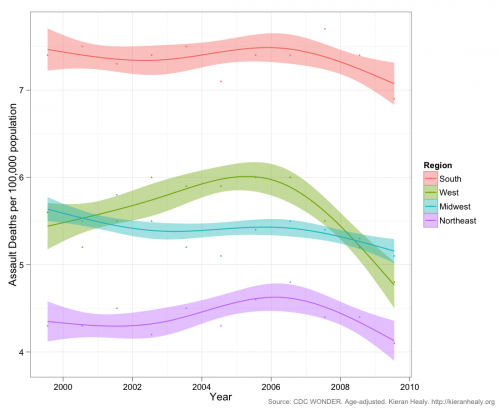

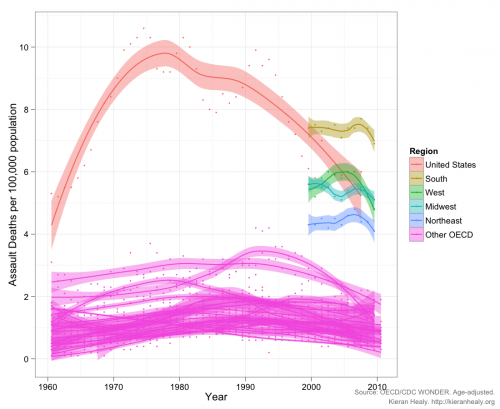

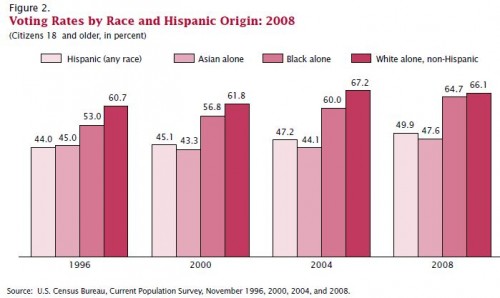

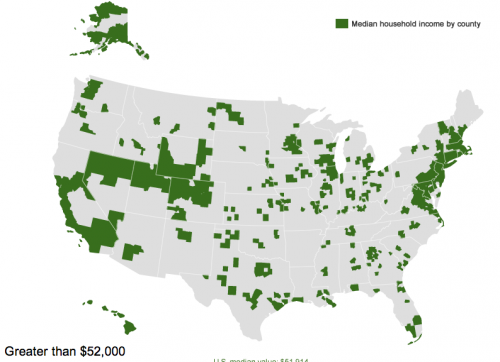

Consider two measures of child well-being according to their mothers’ age at birth. First, infant mortality:

Health prospects for children improve as women (and their partners) increase their education and incomes, and improve their health behaviors, into their 30s. Beyond that, the health risks start accumulating, weighing against the socioeconomic factors, and the danger increases.

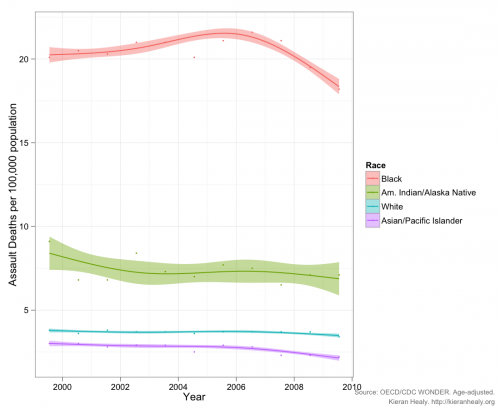

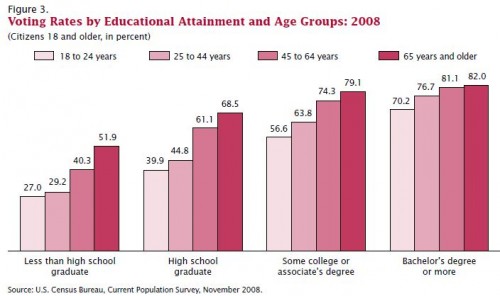

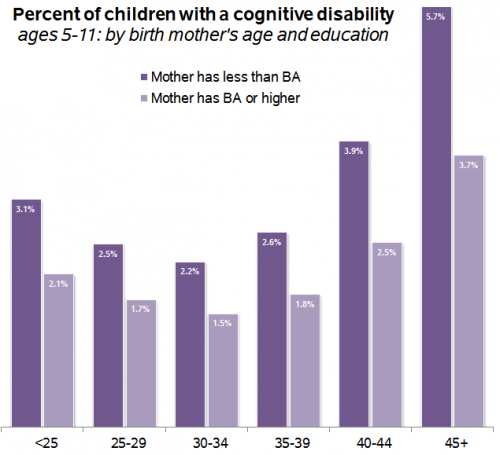

Second, here is the rate of cognitive disability among children according to the age of their mothers at birth, showing a very similar pattern:

Again, the lowest risks are to those born when their parents are in their early 30s, a pattern that holds when I control for education, income, race/ethnicity, gender, and child’s age.

When mothers older than age 40 give birth, which accounted for 3 percent of births in 2011, the risks clearly are increased, and Shulevitz’s story is highly relevant. But, at least in terms of mortality and cognitive disability, an average parental age in the late 20s and early 30s is not only not a problem, it’s ideal.

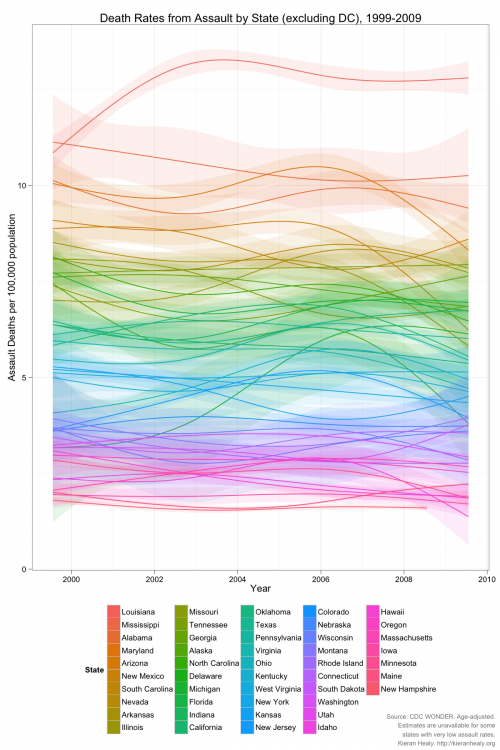

Unequal health

But the second figure above hints at another problem — inequality in the health of parents and children. On that purple chart, a college graduate in her early 40s has the same risk as a non-graduate in her late 20s. And the social-class gap increases with age. Why is the rate of cognitive disabilities so much higher for the children of older mothers who did not finish college? It’s not because of their biological clocks or genetic mutations, but because of the health of the women giving birth.

For healthy, wealthy older women, the issue of aging eggs and genetic mutations from fathers’ run-down sperm factories are more pressing than it is for the majority of parents, who have not graduated college.

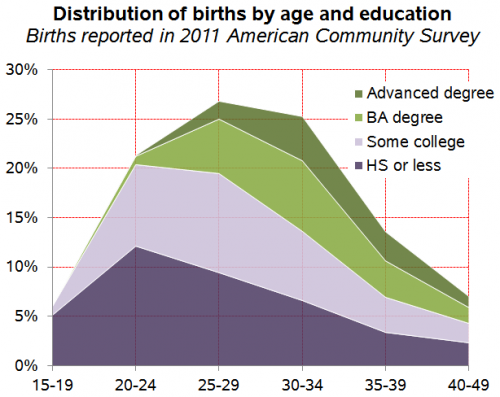

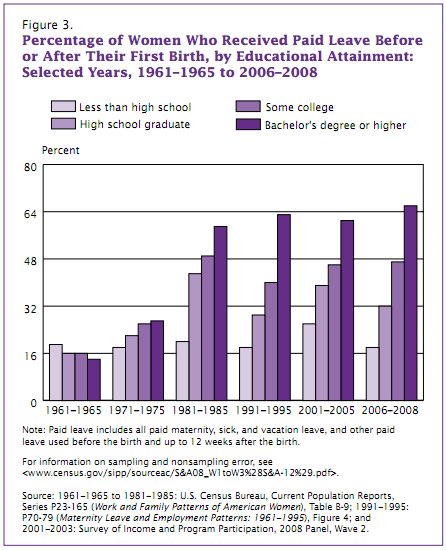

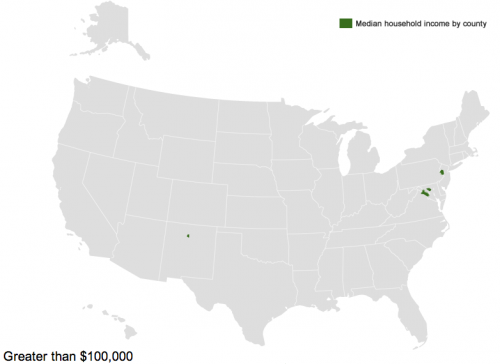

If you look at the distribution of women having babies by age and education, it’s clear that the older-parent phenomenon is disproportionately about more-educated women. (I calculated these from the American Community Survey, because age-by-education is not available in the CDC numbers, so they are a little different.)

Most of the less-educated mothers are giving birth in their 20s, and a bigger share of the high-age births are to women who’ve graduated college — most of them married and financially better off. But women without college degrees still make up more than half of those having babies after age 35, and the risks their children face have more to do with high blood pressure, obesity, diabetes, and other health conditions than with genetic or epigenetic mutations. Preterm births, low birth-weight, and birth complications are major causes of developmental disabilities, and they occur most often among mothers with their own health problems.

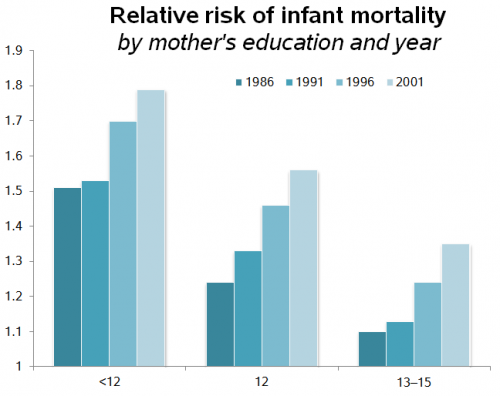

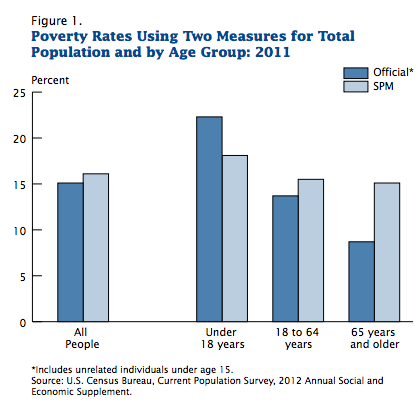

Most distressing, the effects of educational (and income) inequality on children’s health have been increasing. Here are the relative odds of infant mortality by maternal education, from 1986 to 2001, from a study in Pediatrics. (This compares the odds to college graduates within each year, so anything over 1.0 means the group has a higher risk than college graduates.)

This inequality is absent from Shulevitz’s essay and most of the commentary about it. She writes, of the social pressure mothers like her feel as they age, “Once again, technology has given us the chance to lead our lives in the proper sequence: education, then work, then financial stability, then children” — with no consideration of the 66 percent of people who have reached their early 30s with less than a four-year college degree. For the vast majority of that group, the sequence Shulevitz describes is not relevant.

In fact, if Shulevitz had considered economic inequality, she might not have been quite as worried about advancing parental age. When she worries that a 35-year-old mother has a life expectancy of just 46 more years — years to be a mother to her child — the table she consulted applies to the whole population. She should breathe a little bit easier: Among 40-year-old white college graduates women are expected to live an average extra five years compared with those who have a high school education only.

When it comes to parents’ age versus social class, the challenges are not either/or. We should be concerned about both. But addressing the health problems of parents — especially mothers — with less than a college degree and below-average incomes is the more pressing issue — both for potential lives saved or improved and for social equality.

Philip N. Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park, and writes the blog Family Inequality. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook.