Social science bloggers have been buzzin’ over whether drag performance is offensive and to whom. I have been researching and doing drag through a queer feminist anthropology lens for two years. I’ve taken an autoethnographic approach in an attempt to fill the scholarly gap where a male-bodied researcher, specifically a queer one, has lacked the enthusiasm to habitually perform as a drag queen. The motivations for this post easily align with my research as I hope to further develop the trending conversations of drag and its meanings.

Is drag offensive? It’s necessary to specify that this conversation is primarily about drag queening men. This is what most people would think of in terms of “drag queen,” a cisman who dresses as a woman on a stage, which I argue is a limiting definition. Five or ten years ago I would not have to specify “drag queening men,” but today there are genderqueer performers, ciswomen, transwomen – all bodies participate in drag as an expression, and not necessarily while cross dressing. Drag queens embody a range of femininities and masculinities (and sometimes species).

So, are drag queening men offensive? I keep in mind the ultimate queer mantra – both/and.

Looking to literature, this is an argument worked out back in the high Butler days. Esther Newton started this dialogue in the ‘70s and it was clearly closed out by Rupp and Taylor (and Shapiro) in the last decade. There are plenty of lit reviews to read on this [tired] subject.

Drag queening implies an individual who performs and embodies femininities for some kind of audience. Historically, and today, the majority of queens are male bodied. Some may continue this femininity off the stage, others do not. Their identities are assumed to be cis men, but this is incredibly complicated by the fluidity of drag bodies and the politics of the “transgender” category.

Regardless, you have male bodies who are distinctly breaking heteronormative ideas of identity and performance. Drag queening is a subversive outlet for male bodies to participate in gender play, oftentimes exploring femininity within themselves that they have been socialized to fear. Doing drag successfully is “working it” — you don’t give a shit about the patriarchy, your parent’s disappointment, getting fired from your job, or who will think you are date-able. It’s breaking out of boxes. Drag is a display of who you are (or just a part of yourself) and telling everyone to deal with it. If you like what you see, feel free to tip a dollar.

Drag claims the labels “offensive” and “radical” because its goal is to disrupt and show the audience that some identities, especially gender, are more fluid and performed than we think. Drag pokes holes into rigid ideas of gender and sexuality that most choose to ignore. Drag queening men are defiant, messy cyborgs, performing fluid and simultaneous contradictions of femininities and masculinities through their bodies. And of course, there is an entire history of drag acting as an important mode of protest, resistance, and survival for the queer community.

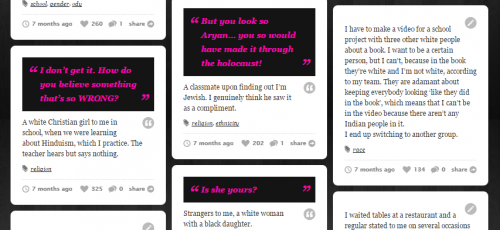

At the same time, drag queens are people who live in the same society that we all do. Drag is an institution that still exists — and always will — within the larger social structures. So, drag queens can be racist, transphobic, homophobic, and even more problematic. The best example for this is the drag queening man who takes her microphone privileges too far, such as a joke about a trans audience member’s genitals.

Drag queening men will often claim immunity under the trans umbrella or argue for the sanctity of comedy, but the reality is that drag queening men do have an underlying rhetoric of transphobia. The reminders that they return to presenting as men after the performance (“This is just a job, I don’t want to be a woman!”) are an unneeded distance created by drag queening men who are afraid and feel an attack against their masculinity. The heteropatriarchy suggests that male bodies who express femininity should fit into a more complicit, fictionally ideal “transsexual woman” category where all parts match behaviors. Some drag queening men respond to this pressure with transphobic masculinity, disastrously reinstating the binary they work to dismantle. It’s also in part to the idea that hegemonic forces continually pressure marginalized groups to create an Other, even if they are part of the same “community.”

Similarly, drag queening men still participate in hegemonic masculinity, and so they may make misogynistic jokes or may think domestic abuse makeup is some kind of “high fashion” (which is the WORST). Drag pageantry can be racially segregated and transwomen can be discouraged through the exclusionary bans of hormones and surgeries. Drag queening men can be soaked in privilege — using the T-slur, blackface, or feeling authority over female-bodied audience members. Most drag queening men have the ability to take off their wigs and makeup to “pass” outside queer spaces.

This in no means is an apology toward these actions, but I feel a stress needed to be made that the tradition of drag queening, a male body performing femininities, is not offensive. It stands as a transgressive act of male bodies deviating from and deconstructing the binary of gender. When drag queening men remind an audience they have a penis, it explodes the heteropatriarchy and dislocates gender from the body. For my own purposes in research and performance, drag is a safe place to explore forbidden femininities, freely navigate bodily inscription, and embrace corporeal versatility.

The tradition of drag queening is not an offensive act, but drag performers may abuse privilege and create problematic messages regardless of their intent. The problems of drag as an institution are the pre-existing racist heteropatriarchal structures that impede upon it. These difficulties with drag are the same hegemonic forces which delve deep into our film, art, video games and universities.

In closing, it is impossible to ignore the reality that groups of people think drag is offensive and no feelings should be ignored. I have no answer as to how this claim of offense can be processed besides our scholarly discussions, but I do hope that drag performers take care to be consciously aware of their privileges and prejudices, remembering their duties as queens who take down the heteropatriarchy one lip sync at a time.

Ray Siebenkittel is a student in the anthropology MA program at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. They take a feminist anthropologist approach to studying drag performance. You can follow their blog, where this post originally appeared, or meet them on twitter.