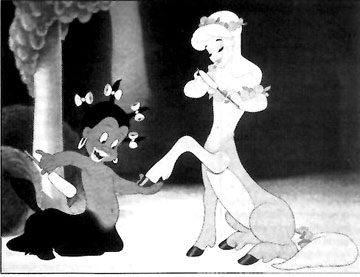

The centaur scene in Disney’s highly acclaimed cartoon Fantasia (1940) clearly communicates gendered expectations for men and women, but there are also racial politics. First, note that, in the film as released, all of the centaurs end up in color-matched heterosexual pairs. Second, most people do not know that the original centaur scene included a pickaninny slave to the centaur females and exotic, brown-skinned zebra-girl servants.

Here’s a link to the whole thing (embedding disabled, but it works as of Feb. ’11).

A clear still in black and white:

Fuzzy color stills from the youtube clip:

Don’t miss our post showing bugs bunny in blackface, too.