Privilege comes in many forms: class privilege, white privilege, male privilege, heterosexual privilege and so on. Being privileged means that you “fit” in the society in which you live and reap rewards by virtue of just being.

Recognizing privilege isn’t just a matter of being thoughtful or empathetic, it usually involves sacrificing something. Sometimes it’s something big (like the belief that your success is due entirely to your talents and hard work) and sometimes it’s something small.

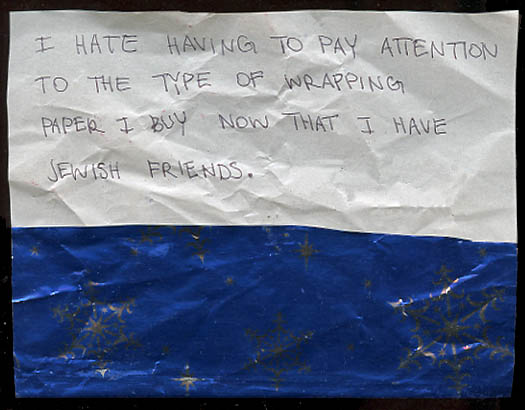

The person who sent this confession to PostSecret is admitting to feeling frustrated by giving up one of those small benefits that come with privilege:

Originally posted in 2009.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.