In the late 1990s, I turned down my publisher’s offer to do a third edition of my criminology textbook. It wasn’t just that editions one and two had failed to make me a man of wealth and fame. But it was clear that crime had changed greatly. Rates of murder and robbery had fallen by nearly 50%; property crimes like car theft and burglary were also much lower. Anybody writing an honest and relevant book about crime would have a lot of explaining to do. And that would be a lot of work.

I politely declined the publisher’s offer. They didn’t seem too upset.

If I had undertaken the project, I probably would have relied heavily on the research articles in The Crime Drop in America, edited by Al Blumstein and Joel Wallman. They rounded up the usual suspects – the solid economy, new police strategies, the incarceration boom, the stabilization of drug markets, anti-gun policies. But we all missed something important – lead. Children exposed to high levels of lead in early childhood are more likely to have lower IQs, higher levels of aggression, and lower impulse-control. All those factors point to crime when children reach their teens if not earlier.

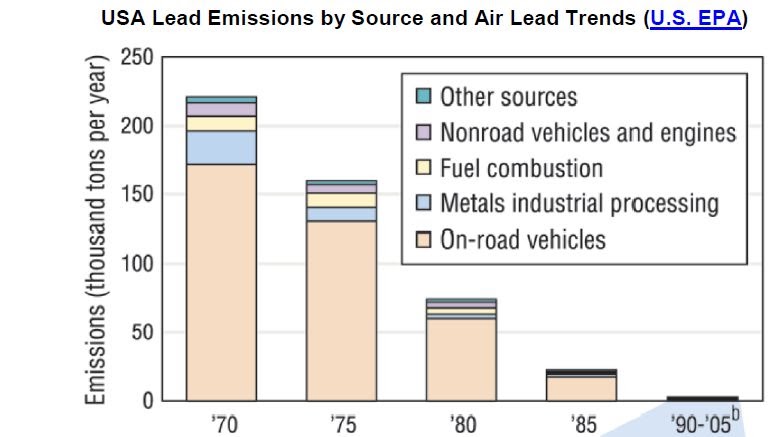

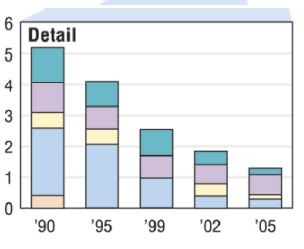

Lead had long been suspected as a toxin, and even before World War I many countries acted to ban or reduce lead in paint and gasoline. But the U.S., thanks to the anti-regulatory efforts of the industries and support from anti-regulation, pro-business politicians, did not undertake serious lead reduction until the 1970s.

Kevin Drum at Mother Jones has been writing about lead and crime. Because race differences on both variables are so great, it’s useful to look at Blacks and Whites separately. In the late 1970s, 15% of Black children under age three had dangerously high rates of lead in their blood (30 mcg/dl or higher). Among Whites, that rate was only 2.5%. By 1990, even with a lower criterion level of 25 mcg/dl, those rates had fallen to 1.4% and 0.4%, respectively.

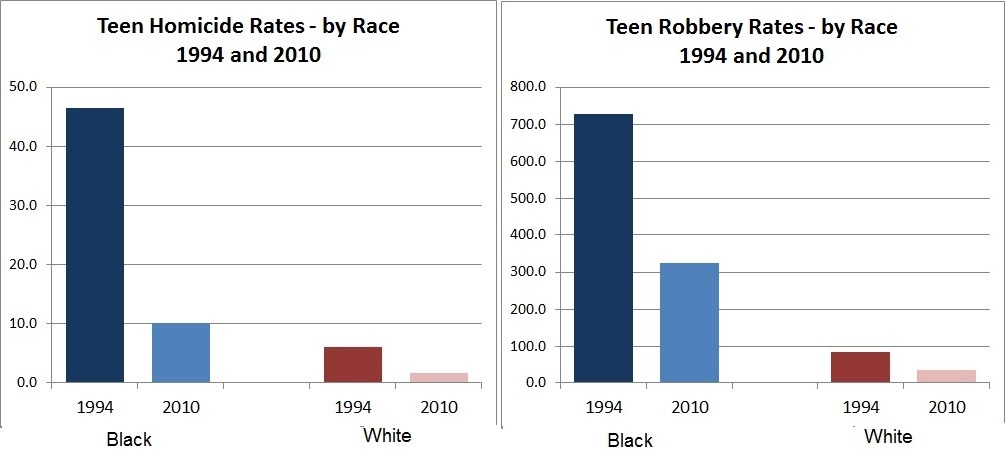

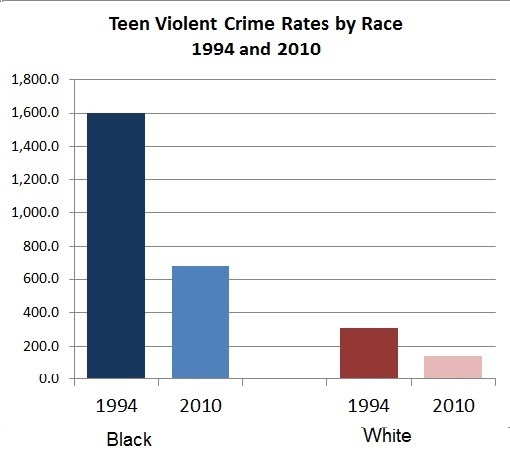

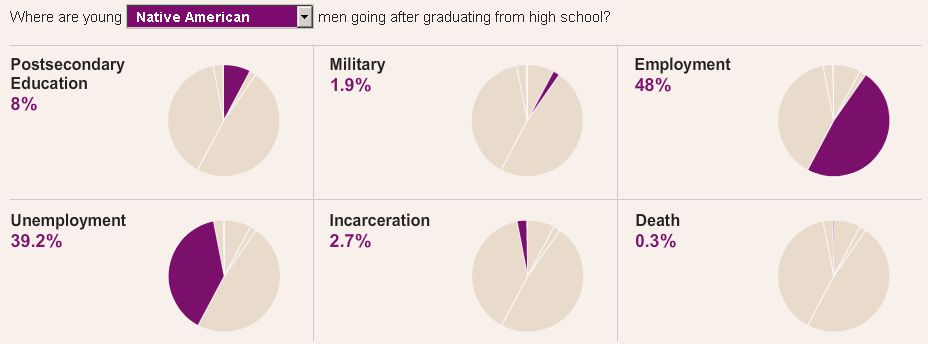

The huge reduction in lead was matched – years later when those children were old enough to commit crimes – with a reduction in crime. (note that the graphs show rates of arrest, which may somewhat exaggerate Black rates of offending):

Much of the research pointing to lead as an important cause of crime looks at geographical areas rather than individuals. A study might compare cities, measuring changes in lead emissions and changes in violent crime 20 years later. But studies that follow individuals have found the same thing. Kids with higher blood levels of lead have higher rates of crime. The lead-crime hypothesis is fairly recent, and the evidence is not conclusive. But my best guess is that further research will confirm the idea that getting the lead out was, and will remain, an important crime-reduction policy.

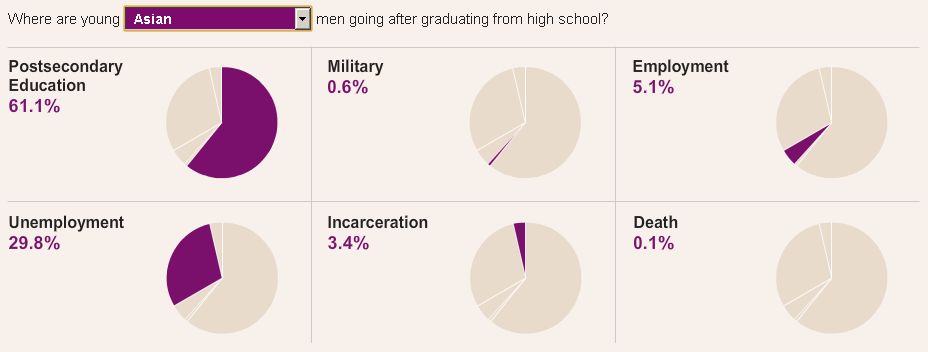

Kevin Drum also emphasizes race differences. And here the evidence is less solid:

[A]rrest rates for violent crime have fallen much faster among black juveniles than among white juveniles… black juvenile crime rates fell further than white juvenile crime rates because they had been artificially elevated by lead exposure at a much higher rate.

But that depends on how you intepret the data. As the graphs of arrests show, the percentage reductions are roughly similar across races. Among Black youths, the arrest rates for all violent crime fell from 1600 per 100,000 to less than 700 – a 57% reduction. For Whites the reduction was from 307 to 140 or 54%. But in absolute numbers, because Black rates of criminality were so much higher, the reduction seems all the more impressive. In that sense, those rates “fell further.”

Arrest rates for Blacks are still double those of Whites for property crimes, five times higher for homicide, and nine times higher for robbery. Lead may be a factor in those differences. Remember the lag time between childhood lead exposure and later crime. Twenty years ago, high blood levels of lead among children 1-5 years were three times as high for Blacks as for Whites.

Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.