In conversation, I keep accidentally referring to Zimmerman’s defense lawyers as “the prosecution.” Not surprising, because the defense of George Zimmerman was only a defense in the technical sense of the law. Substantively, it was a prosecution of Trayvon Martin. And in making the case that Martin was guilty in his own murder, Zimmerman’s lawyers had the burden of proof on their side, as the state had to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Martin wasn’t a violent criminal.

This raises the question, who’s afraid of young black men? Zimmerman’s lawyers took the not-too-risky approach of assuming that white women are (the jury was six women, described by the New York Times as five white and one Latina).

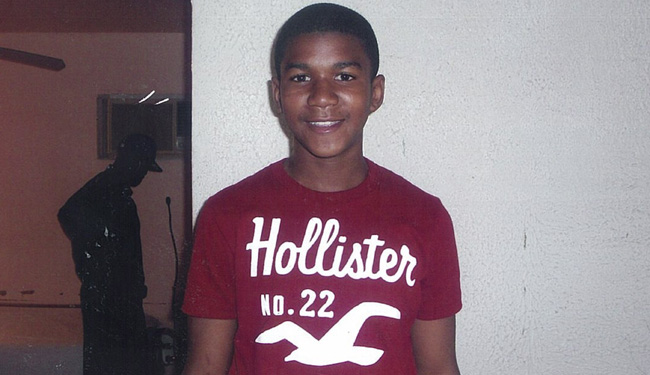

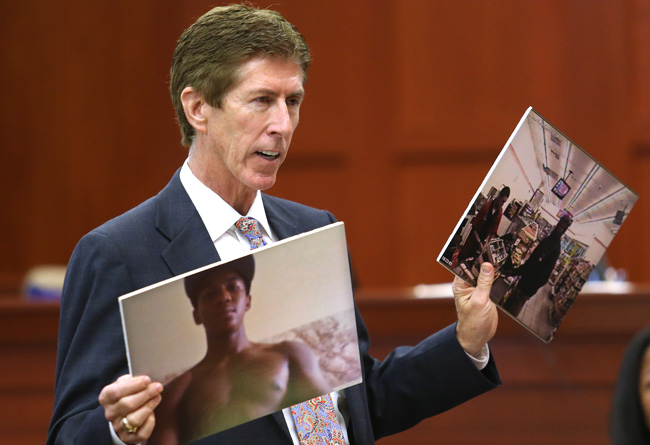

“This is the person who … attacked George Zimmerman,” defense attorney Mark O’Mara said in his closing argument, holding up two pictures of Trayvon Martin, one of which showed him shirtless and looking down at the camera with a deadpan expression. He held that shirtless one up right in front of the jury for almost three minutes. “Nice kid, actually,” he said, with feigned sincerity.

Going into the trial, according to one analysis, the female jurors were supposed to have more negative views about Zimmerman’s vigilante behavior, and be more sympathetic over the loss of the child Trayvon. As a former prosecutor put it:

With the jury being all women, the defense may have a difficult time having the jurors truly understand their defense, that George Zimmerman was truly in fear for his life. Women are gentler than men by nature and don’t have the instinct to confront trouble head-on.

But was the jury’s race, or their gender, the issue? O’Mara’s approach suggests he thought it was the intersection of the two: White women could be convinced that a young black man was dangerous.

Race and Gender

Racial biases are well documented. With regard to crime, for example, one recent controlled experiment using a video game simulation found that white college students were most likely to accidentally fire at an unarmed suspect who was a black male — and most likely to mistakenly hold fire against armed white females. More abstractly, people generally overestimate the risk of criminal victimization they face, but whites are more likely to do so when they live in areas with more black residents.

The difference in racial attitudes between white men and women are limited. One analysis by prominent experts in racial attitudes concluded that “gender differences in racial attitudes are small, inconsistent, and limited mostly to attitudes on racial policy.” However, some researchers have found white men more prone than women to accept racist stereotypes about blacks, and the General Social Survey in 2002 found that white women were much more likely than men to describe their feelings toward African Americans positively. (In 2012, a minority of both white men and white women voted for Obama, although white men were more overwhelmingly in the Romney camp.)

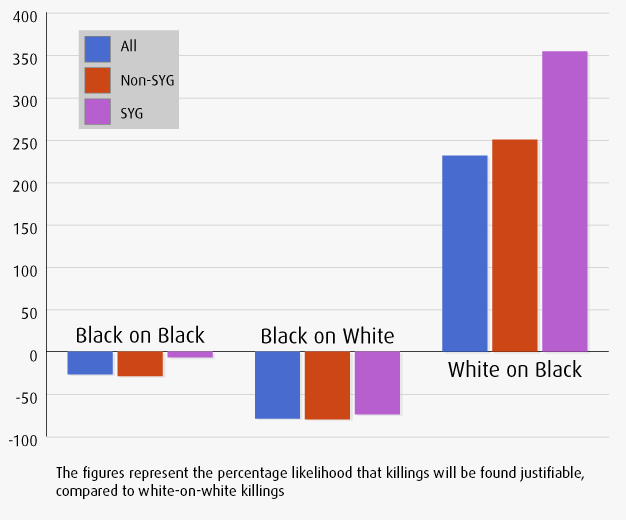

What about juries? The evidence for racial bias over many studies is quite strong. For example, one 2012 study found that in two Florida counties having an all-white jury pool – that is, the people from which the jury will be chosen – increased the chance that a black defendant would be convicted. Since the jury pool is randomly selected from eligible citizens, unaltered by lawyers’ selections or disqualifications, the study has a clean test of the race effect. But I can’t find any on the combined influence of race and gender.

The classical way of framing the question is whether white women’s group identity as whites is strong enough to overcome their gender-socialized overall “niceness” when it comes to attitudes toward minority groups. But Zimmerman’s lawyers appeared to be invoking a very specific American story: white women’s fear of black male aggression. Of course the “victim” in their story was Zimmerman, but as he lingered over the shirtless photo, O’Mara was tempting the women on the jury to put themselves in Zimmerman’s fearful shoes.

Group Threat

But do white women really feel threatened by black men? That’s an old, blood-stained debate. In the 20th century there were 455 American men (legally) executed for rape, and 89 percent of them were black — most were accused of raping white women. That was just the legal tip of Jim Crow’s lynching iceberg, partly driven by white men asserting ownership over white women in the name of protection. But the image of course lives on.

In the specific realm of U.S. racial psychology, one of the less optimistic, but most reliable, findings is that whites who live in places with larger black populations on average express more racism (here’s a recent confirmation). Most analysts attribute that to some sense of group threat – economic, political, or violent – experienced by the dominant majority.

Because people inflate things they are afraid of, you can get a ballpark idea of how threatened white people feel by asking them how big they think the black population is. And since they don’t realize their racial attitudes are being measured, they aren’t as likely to shade their answers to appear reasonable.

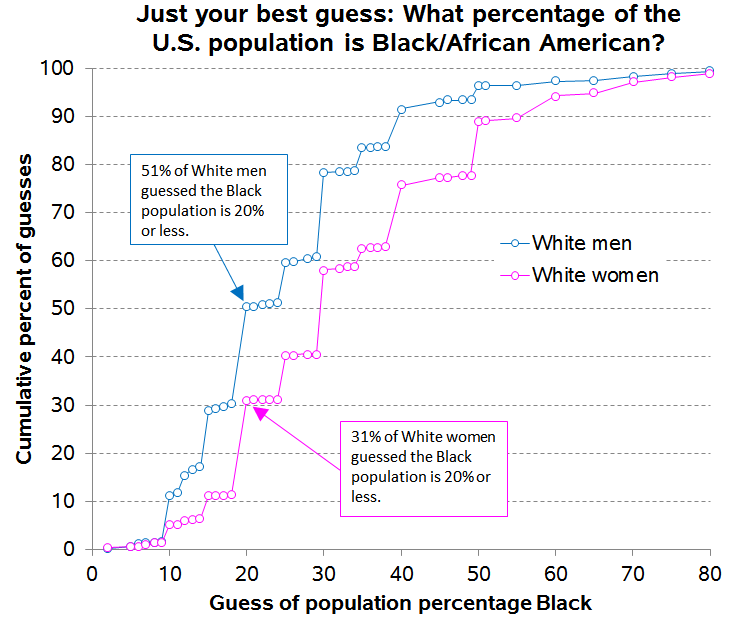

The 2000 General Social Survey asked about 1,000 white adults to estimate the size of the black population. Both groups were way off, of course: 95 percent of white women and 85 percent of white men overestimated. But the skew was stronger for women than men: 69 percent of women and 49 percent of men guessed that blacks are more than 20 percent of the population (the correct answer at the time was 12 percent).

Here are those results, showing the cumulative percentage of white men and women who thought the black population was at or below each level:

Maybe white women’s greater overestimation of the black population is not an indicator of perceived threat. In the same survey white women were no more likely than white men to describe blacks as “prone to violence” (then again, there’s social pressure to say “no”). Anyway, whether women feel more threatened than men do isn’t the issue, since the jury was all women. The question is whether the perceived threat was salient enough that the defense could manipulate it.

I don’t know what was in the hearts and minds of the jurors in this case, of course. Being on a jury is not like filling out a survey or playing a video game. But however much we elevate the rational elements in the system, emotion also plays a role. Whether they were right or not, Zimmerman’s lawyers clearly thought there was a vein of fear of black men inside the jurors’ psyches, waiting to be mined.

Originally posted at The Atlantic and Family Inequality.

Philip N. Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park, and writes the blog Family Inequality. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook.