Prisoners who can maintain ties to people on the outside tend to do better — both while they’re incarcerated and after they’re released. A new Crime and Delinquency article by Joshua Cochran, Daniel Mears, and William Bales, however, shows relatively low rates of visitation.

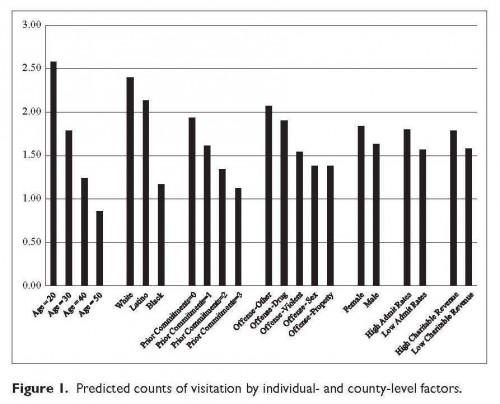

The study was based on a cohort of prisoners admitted into and released from Florida prisons from November 2000 to April 2002. On average, inmates only received 2.1 visits over the course of their entire incarceration period. Who got visitors? As the figure below shows, prisoners who are younger, white or Latino, and had been incarcerated less frequently tend to have more visits. Community factors also shaped visitation patterns: prisoners who come from high incarceration areas or communities with greater charitable activity also received more visits.

There are some pretty big barriers to improving visitation rates, including: (1) distance (most inmates are housed more than 100 miles from home); (2) lack of transportation; (3) costs associated with missed work; and, (4) child care. While these are difficult obstacles to overcome, the authors conclude that corrections systems can take steps to reduce these barriers, such as housing inmates closer to their homes, making facilities and visiting hours more child-friendly, and reaching out to prisoners’ families regarding the importance of visitation, both before and during incarceration.

Cross-posted at Public Criminology.

Chris Uggen is a professor of sociology at the University of Minnesota and the author of Locked Out: Felon Disenfranchisement and American Democracy, with Jeff Manza. You can follow him at his blog and on twitter.