Nearly two years ago I wrote a post about the discovery that the president of Jacksonville State University blatantly plagiarized large segments of his dissertation. Yet his Ph.D. was not revoked, nor did he lose his job or face any discipline, as far as I know.

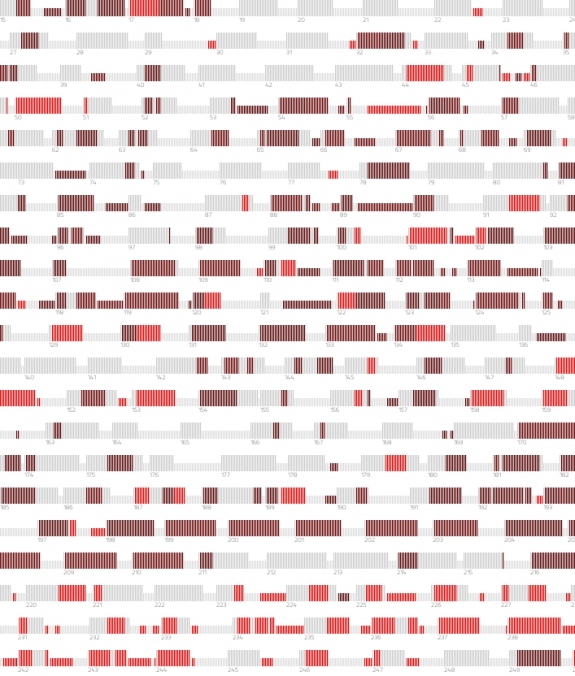

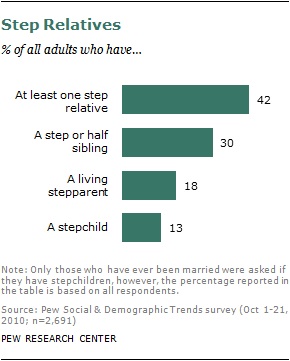

Another case recently came to light. Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg, Germany’s Defense Minister, admitted plagiarizing part of his dissertation. Flowing Data posted this graph, created by Gregor Aisch, that visualizes the extent of the plagiarism. The taller bars represent regular text, while the shorter bars are footnotes. The dark red bars are direct plagiarism; the bright red ones are “other” plagiarism, which I can’t explain to you because the page about it is in German:

In this case, however, status didn’t outweigh the plagiarism. The University of Bayreuth, where he earned his J.D. degree, revoked it; over 20,000 academics signed a petition to Chancellor Merkel complaining about her continued support for Guttenberg; and he ultimately resigned.

UPDATE: Reader Kat asked that I provide the link to the original source, GuttenPlag Wiki. Kat explains,

The dissertation was NOT run just through a computer programme- it was posted on the internet and then people “crowd-sourced” passages to find where they were really from.

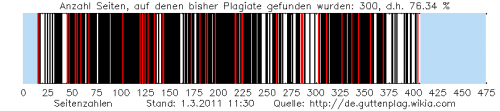

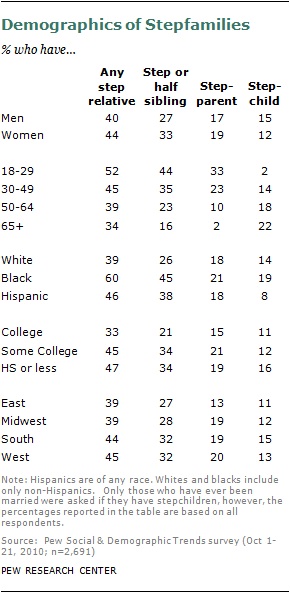

Secondly, there is another good graphic that I believe you should include in your post lower down on the page I posted above:

– Black are pages on which one source was plagiarized

– Red are pages with plagiarism of more than one single source

– White are pages where SO FAR no plagiarism has been found

– Light blue are the index and annexesIn total Baronet zu Guttenberg plagiarized 76.34 % of his dissertation (annexes and index were not included to compute this percentage).

Thirdly: The entire dissertation was VERY likely written by a ghost writer. Guttenberg was a Member of Parliament the entire time when the PhD was allegedly “written” (copy and pasted).

Here is the image she desscribes from the GuttenPlag Wiki page:

And reader Ellen says,

I took a crack at the German explanation of the “other plagiarism” and I think it refers to instances where the source was incorrectly cited, quotation marks were conveniently forgotten and other things of that nature. In other words, plagiarism that isn’t directly copied and pasted.

I suspect the academic world would be horrified by the results if someone had time to sit down and systematically run dissertations through anti-plagiarism software.

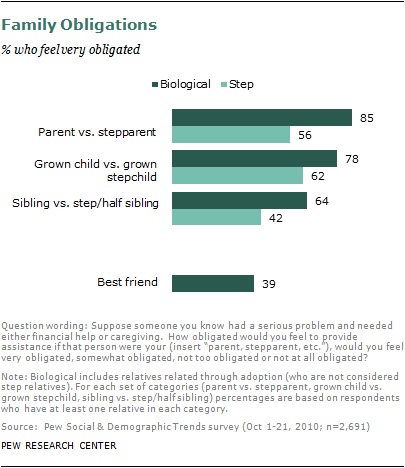

UPDATE 2: Kat sent along another link that makes the degree of plagiarism even more obvious. It shows in thumbnail form each page that has plagiarism, and you can click on the thumbnail to see a side-by-side comparison of the original and Guttenberg’s dissertation. The updated Wiki page indicates that over 94% of pages were plagiarized. Finally, she clarifies what “other plagiarism” means:

- A source text in a language other than German was translated word by word, with no quotation marks. The translation was made by the “Wissenschaftliche Dienst” (Science Service) of the Bundestag (German equivalent to CRS). So he illegally let them do research for his PhD (claiming it was for his work as MP)

- plagiarism of structure: The structuring of an argument or an index or a graphic e.g.

- Alibi footnote: There is a footnote, but it is insufficient. For example, a huge passage is an actual quotation, but the footnote and citation marks make it look as if only part of the sentence is a direct quote.

- Shake & Paste: The text is made up of fragments of another text which were rearranged.