Religious freedom and discrimination are back in the national spotlight, from this year’s Masterpiece Cakeshop case in the Supreme Court to Jeff Sessions’ new Religious Liberty Task Force. These cases are controversial because they raise questions about the limits of freedom—do people with sincere religious beliefs (often conservative Christians) have a right to opt out of providing goods and services they do not support? Or, is that just plain discrimination?

Debates about religious freedom often jump to legal arguments, but there is also a sociological angle on these controversies: who experiences bias and who perceives bias? For example, my research at the American Mosaic Project found that Atheists and Muslims face the strongest animus in the US, at almost twice the rate of conservative Christians. Trends in hiring discrimination tend to follow a similar pattern. Yet many of these recent religious freedom cases focus on conservative Christians alleging discrimination. Does perceived bias run the other way?

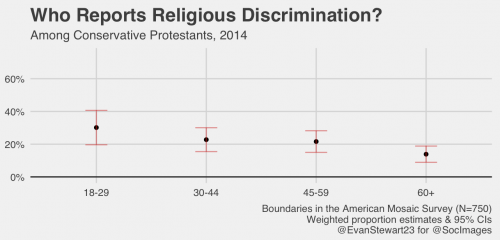

Sociologist John W. Hawthorne recently shared some interesting research from the annual conference of the Association for the Sociology of Religion. His surveys of evangelical clergy found older clergy members tended to agree that society regularly discriminates against people with Christian beliefs, while younger clergy were more likely to disagree. I went back to data from the American Mosaic Project to see if a similar pattern shows up for members of these religious denominations.

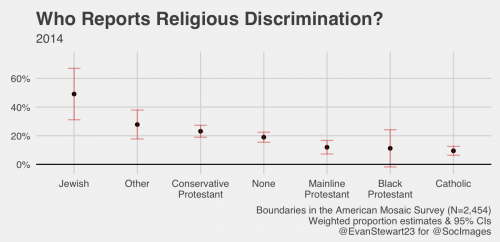

In this survey, respondents answered a simple yes or no question about whether they had ever experienced discrimination because of their religion. The chart below breaks down the percentage of responses who said they did by major denomination groups. It is important to remember that many minority religious groups in the US are actually quite small, so getting useful information requires putting many groups into a big “other” category and using confidence intervals to show uncertainty in our estimates.

Conservative Protestants are different from other Protestant groups, with about 23% reporting that they have experienced religious discrimination. This proportion is fairly high, third in line after respondents who are Jewish or belong to other religious minority groups. They even nudged out people with no religious affiliation. What about age brackets?

This is different from John Hawthorne’s finding. Younger members of conservative Protestant groups reported experiencing discrimination at higher rates than older members. This is just a quick look, but we can speculate about an explanation. Younger conservative Protestants and evangelicals live in a very secular generation, and probably perceive tension and conflict outside the church. Younger clergy, on the other hand, probably have a different perspective on the changing role of churches in society.

The big sociological questions for the religious freedom debate are how these views persist and how they may skew our interpretation of trends in actual discriminatory behavior.

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, or on BlueSky.