Social institutions are powerful on their own, but they still need buy-in to work. When people don’t feel like they can trust institutions, they are more likely to find ways to opt out of participating in them. Low voting rates, religious disaffiliation, and other kinds of civic disengagement make it harder for people to have a voice in the organizations that influence their lives.

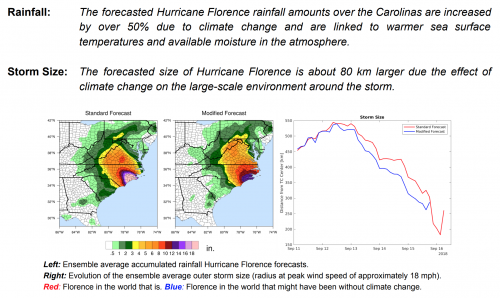

And, wow, have we seen some good reasons not to trust institutions over the past few decades. The latest political news only tops a list running from Watergate to Whitewater, Bush v. Gore, the 2008 financial crisis, clergy abuse scandals, and more.

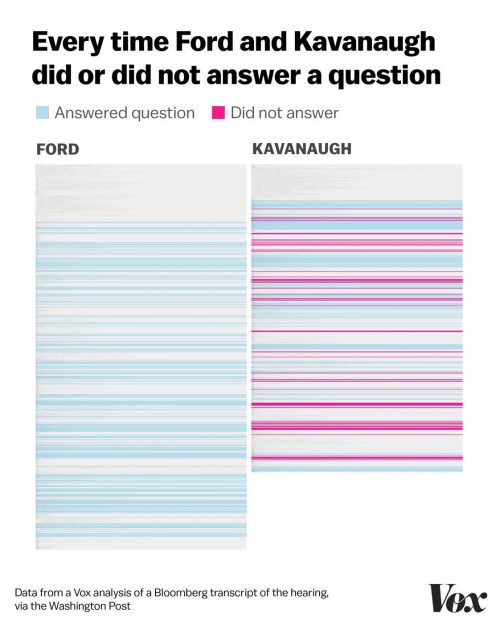

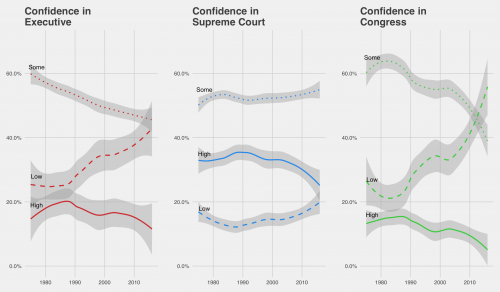

Using data from the General Social Survey, we can track how confidence in these institutions has changed over time. For example, recent controversy over the Kavanaugh confirmation is a blow to the Supreme Court’s image, but strong confidence in the Supreme Court has been on the decline since 2000. Now, attitudes about the Court are starting to look similar to the way Americans see the other branches of government.

Source: General Social Survey Cumulative File

LOESS-Smoothed trend lines follow weighted proportion estimates for each response option.

Over time, you can see trust in the executive and legislative branches drop as the proportion of respondents who say they have a great deal of confidence in each declines. The Supreme Court has enjoyed higher confidence than the other two branches, but even this has started to look more uncertain.

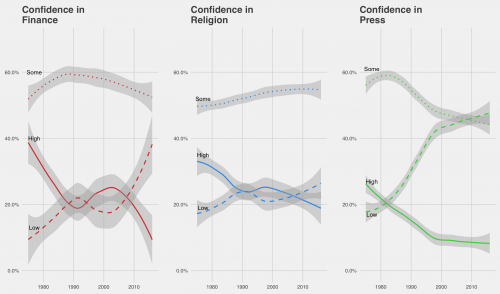

For context, we can also compare these trends to other social institutions like the market, the media, and organized religion. Confidence in these groups has been changing as well.

Source: General Social Survey Cumulative File

It is interesting to watch the high and low trend lines switch over time, but we should also pay attention to who sits on the fence by choosing some confidence on these items. More people are taking a side on the press, for example, but the middle is holding steady for organized religion and the Supreme Court.

These charts raise an important question about the nature of social change: are the people who lose trust in institutions moderate supporters who are driven away by extreme changes, or “true believers” who feel betrayed by scandals? When political parties argue about capturing the middle or motivating the base, or the church worries about recruiting new members, these kinds of trends are central to the conversation.

Inspired by demographic facts you should know cold, “What’s Trending?” is a post series at Sociological Images featuring quick looks at what’s up, what’s down, and what sociologists have to say about it.

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, or on BlueSky.