Democrats and Republicans are deeply divided. By definition, political parties have differences of opinion. But these divisions have widened. Twenty years ago, your opinions on political issues did not line up the way we have come to expect them. Today, when you find you share an opinion with someone about systemic racism, you’re more likely to have like minds about environmental policies, welfare reform, and how they feel about the poor, gay and lesbian people, immigrants and immigration, and much more. In other words, Democrats and Republicans have become more ideologically consistent in recent history.

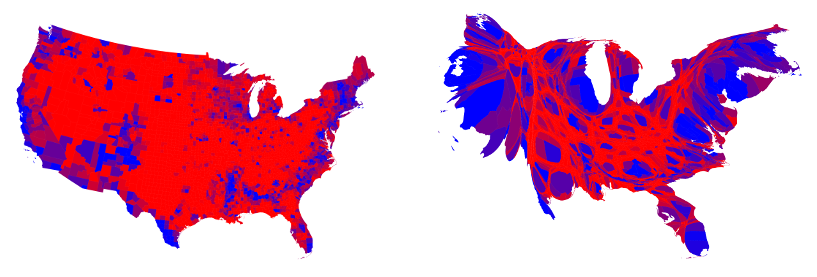

A recent Pew Report reported that in 1994, 64% of Republicans were more conservative than the median Democrat on a political values scale. By 2014, 92% of Republicans were more conservative than the median Democrat. Democrats have become more consistently liberal in their political values and Republicans have become more consistently conservative. And this has led to increasing political polarization (see HERE and HERE for smart posts on this process by Lisa Wade and Gwen Sharpe). You can see political polarization happening below.

You might think ideological commitments naturally come in groupings. But there are lots of illogical pairings without natural connections. Why, for instance, should how you feel about school vouchers be related to how you feel about global warming, whether police officers use excessive force against Black Americans, or whether displays of military strength are the best method of ensuring peace? The four issues are completely separate. But, if your Facebook feed looks anything like mine, knowing someone’s opinion about any one of these issues gives you enough information to feel reasonably confident predicting their opinions about the other three. That’s what ideological consistency looks like.

You might think ideological commitments naturally come in groupings. But there are lots of illogical pairings without natural connections. Why, for instance, should how you feel about school vouchers be related to how you feel about global warming, whether police officers use excessive force against Black Americans, or whether displays of military strength are the best method of ensuring peace? The four issues are completely separate. But, if your Facebook feed looks anything like mine, knowing someone’s opinion about any one of these issues gives you enough information to feel reasonably confident predicting their opinions about the other three. That’s what ideological consistency looks like.

Consider how this process affects understandings of important systems of social inequality that structure American society. Discrimination is an issue that sociologists have studied in great detail. We know that discrimination exists and plays a fundamental role in the reproduction of all manner of social inequalities. But, people have opinions about various forms of discrimination as well—even if they’re unsupported by research or data. And while you might guess that many Americans’ opinions about one form of discrimination will be predictive of their opinions about other forms, there’s not necessarily a logical reason for that to be true. But it is.

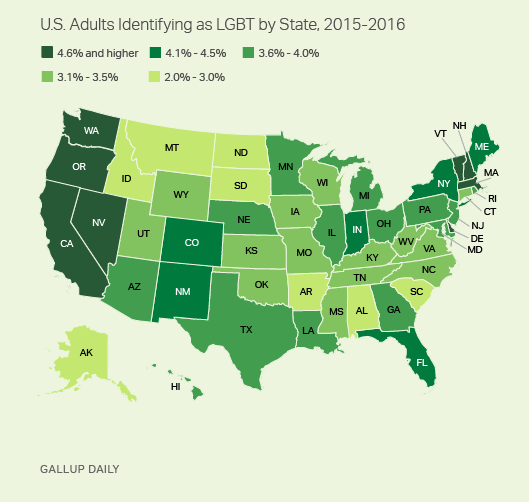

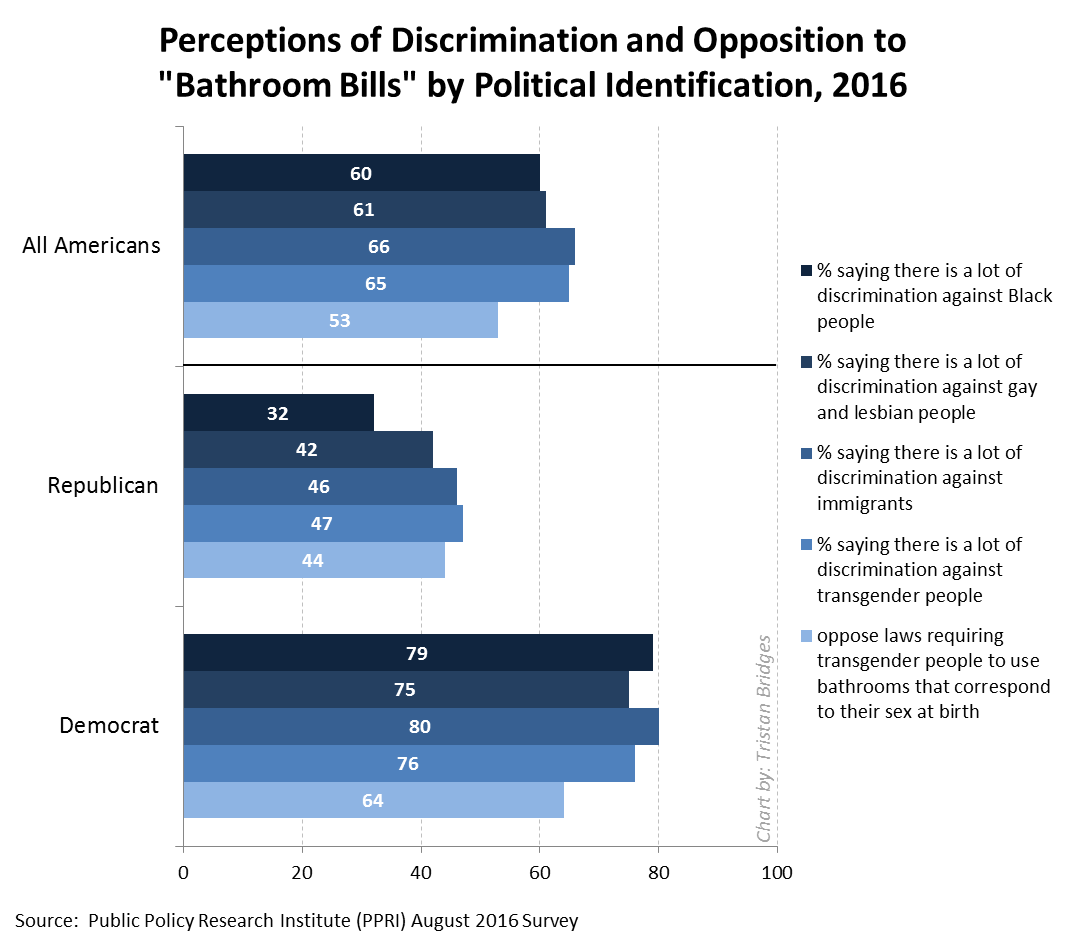

The following chart visualizes the proportions of Americans who say there is “a lot of discrimination” against Black people, gay and lesbian people, immigrants, transgender people, as well as the proportions of Americans who oppose laws requiring transgender people to use bathrooms that correspond to their sex at birth. And you can see how Americans identifying as Democrat and Republican compare.

The majority of Americans understand that social inequalities exist and that discrimination against socially marginalized groups is still a serious problem. By that, I mean that more than half of Americans believe these things to be true. And data support their beliefs. But look at the differences between Democrats’ and Republicans’ opinions about important forms of discrimination in U.S. society. The gap is huge. While just less than 1 in 3 Republicans feels that there is a lot of discrimination against Black people in the U.S., almost 8 in 10 Democrats support that statement. That’s what political polarization looks like. And Pew found that the trend is even more exaggerated among voters.

The majority of Americans understand that social inequalities exist and that discrimination against socially marginalized groups is still a serious problem. By that, I mean that more than half of Americans believe these things to be true. And data support their beliefs. But look at the differences between Democrats’ and Republicans’ opinions about important forms of discrimination in U.S. society. The gap is huge. While just less than 1 in 3 Republicans feels that there is a lot of discrimination against Black people in the U.S., almost 8 in 10 Democrats support that statement. That’s what political polarization looks like. And Pew found that the trend is even more exaggerated among voters.

Republicans and Democrats are not just divided about whether and what to do about forms of social inequality. They’re divided about whether these inequalities exist. And that is an enormous problem.

Tristan Bridges, PhD is a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is the co-editor of Exploring Masculinities: Identity, Inequality, Inequality, and Change with C.J. Pascoe and studies gender and sexual identity and inequality. You can follow him on Twitter here. Tristan also blogs regularly at Inequality by (Interior) Design.