The New York Times has been catching a lot of criticism this week for publishing a profile on the co-founder of the Traditionalist Worker Party. Critics argue that stories taking a human interest angle on how alt-right activists live, and how they dress, are not just puff pieces that aren’t doing due diligence in reporting—they also risk “normalizing” neo-nazi and white supremacist views in American society.

It is tempting to scoff at the buzzword “normalization,” but there is good reason for the clunky term. For sociologists, what is normal changes across time and social context, and normalization means more than whether people choose to accept deviant beliefs or behaviors. Normalization means that the everyday structure of organizations can encourage and reward deviance, even unintentionally.

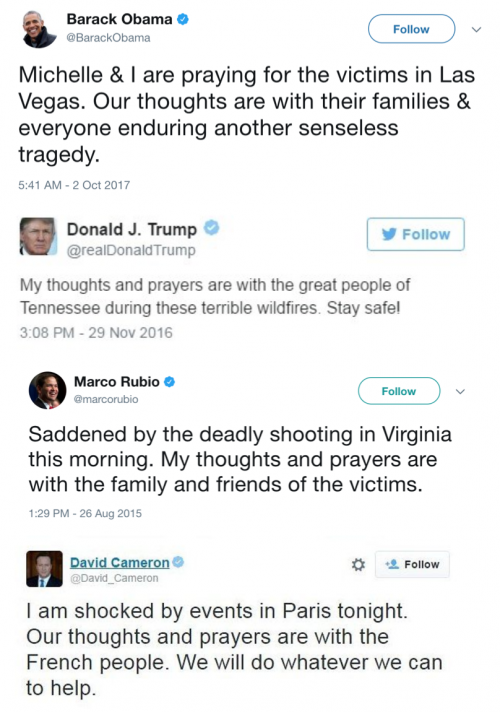

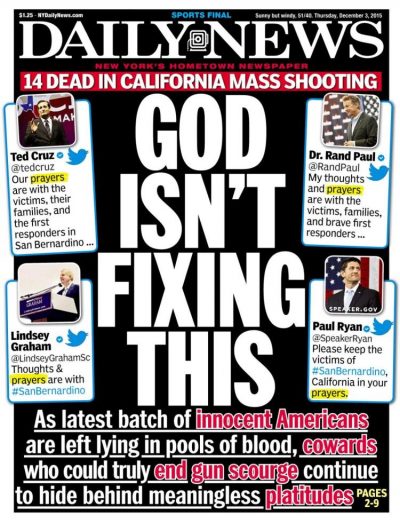

Media organizations play a key role here. Research on the spread of anti-Muslim attitudes by Chris Bail shows how a small number of fringe groups with extremist views were able to craft emotionally jarring messages that caught media attention, giving them disproportionate influence in policy circles and popular culture.

Organizations are also quite good at making mistakes, and even committing atrocities, through “normal” behavior. Research on what happened at NASA leading up to the Challenger disaster by Diane Vaughan describes normalization using a theory of crime from Edwin H. Sutherland where people learn that deviant behavior can earn them benefits, rather than sanctions. When bending the rules becomes routine in organizations, we get everything from corporate corruption up to mass atrocities. According to Vaughan:

When discovered, a horrified world defined these actions deviant, yet they were normative within the culture of the work and occupations of the participants who acted in conformity with organizational mandates

The key point is that normalization doesn’t just stop by punishing or shaming individuals for bad behavior. Businesses can be fined, scapegoats can be fired, and readers can cancel subscriptions, but if normalization is happening the culture of an institution will continue to shape how individual people make decisions.This raises big questions about the decisions made by journalists and editors in pursuit of readership.

Research on normalization also begs us to remember that some of the most horrifying crimes and accidents in human history are linked by a common process: the way organizations can reward deviant work. Just look at the “happy young folks” photographed by Karl Höcker in 1944…while they worked at Auschwitz.

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, or on BlueSky.