Cross-posted at Jezebel and AOL’s Black Voices.

In a new book called “The Protest Psychosis: How Schizophrenia became a Black Disease,” psychiatrist and cultural critic Jonathan Metzl draws on a variety of sources — patient records, psychiatric studies, racialized drug advertisements, and popular metaphors for madness — to contend that schizophrenia transformed from being a mostly white, middle-class affliction in the 1950s, to one that identified with blackness, volatility, and civil strife at the height of the Civil Rights movement.

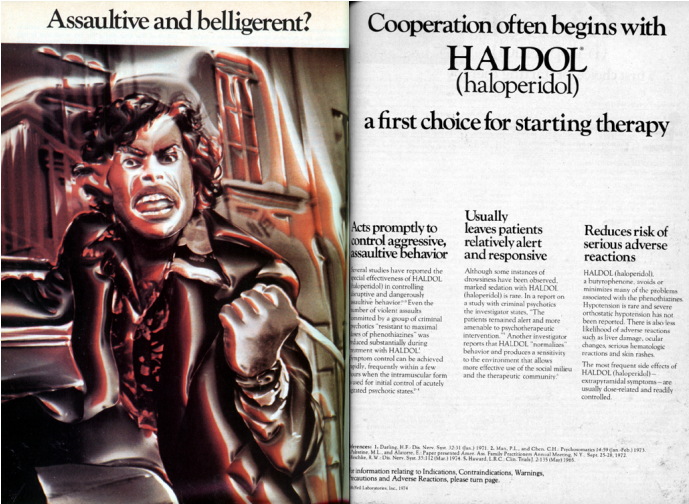

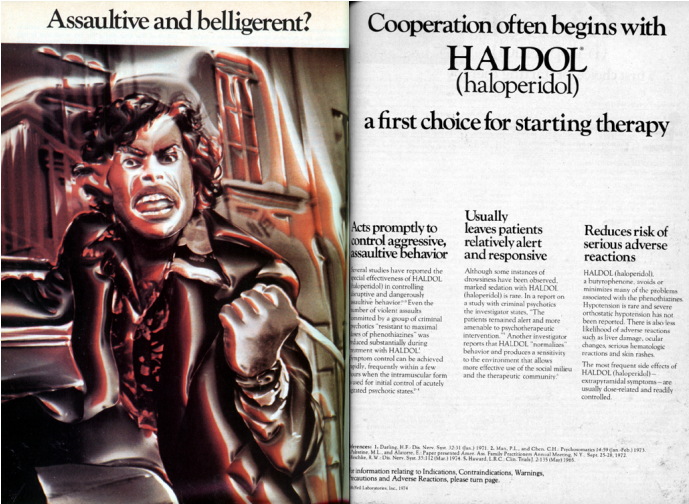

The racialized resonance between emerging definitions of schizophrenia and anxieties about black protest seem clear in pharmaceutical advertisements and essays appearing in leading American psychiatric journals during the 1960s and 70s. For instance, the advertisement for the major tranquilizer Haldol that ran in the Archives of General Psychiatry shows an angry, hostile African American man with a clenched, inverted, Black Power fist.

The deranged black figure literally shakes his fist at the assumed physician viewer, while in the background a burning, urban landscape appears to directly reference the type of civil strive that alarmed many in the “establishment” at that time. The ad compels psychiatrists to conflate black anger as a form of threatening psychosis and mental illness. Indeed the ad seems to play off presumed fears of assaultive and belligerent black men.

As the urban background suggests, this fear extended beyond individual safety to social unrest. In a 1969 essay titled “The Protest Psychosis,” after which Metzl’s book is named, psychiatrists postulated that the growing racial disharmony in the US at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, reflected a new manifestation of psychotic behaviors and delusions afflicting America’s black lower class. Accordingly, “paranoid delusions that one is being constantly victimized” drew some men to fixate on misguided ventures to overthrow the establishment. Luckily, pharmaceutical companies proposed that chemical interventions could directly pacify the masculinzed, black threat depicted in advertisements like the above. “Assaultive and belligerent?” it asks. “Cooperation often begins with Haldol.”

Moreover, ads for Thorazine and Stelazine during this period often conjured up images of the “unruly” and “primitive” precisely at a time when the demographic composition of this diagnosis was dramatically shifting from a mostly white clientele, to a group of predominately black, confined, mental patients. It is telling that within this context, the makers of Thorazine would choose to portray the drug’s supposed specificity to schizophrenia in their advertisements by displaying a variety of war staffs, walking sticks, and other phallic artifacts from African descent.

The below ad for Thorazine, for example, exclaims western medicine’s superiority in treating mental illness with modern pharmaceuticals, by contrasting the primitive tools used by less enlightened cultures.

Notably, these claims of superiority and medical efficacy drew from a particular set of pejorative ideas of the “primitive” that were already well established within some sectors of psychiatry that equated mental illness with primitive, animalistic and regressive impulses. As Metzl contends in his book:

…pharmaceutical advertisements shamelessly called on these long-held racist tropes to promote the message that social “problems” raised by angry black men could be treated at the clinical level, with antipsychotic medications.

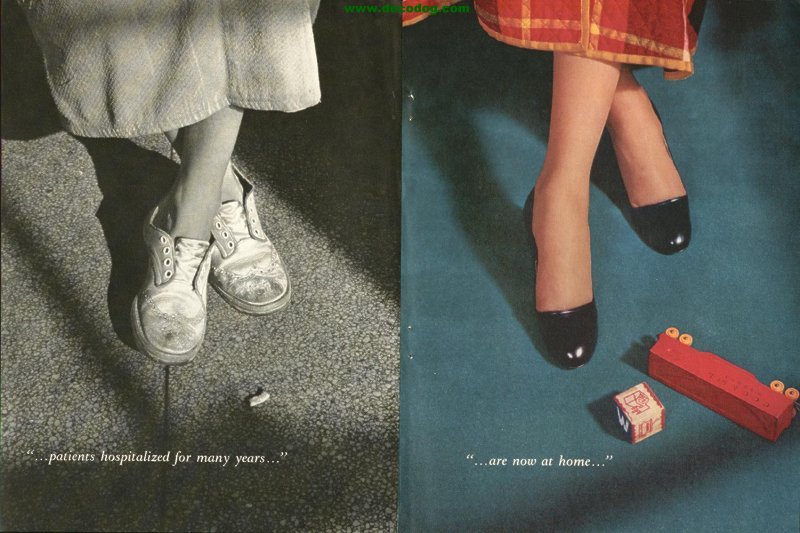

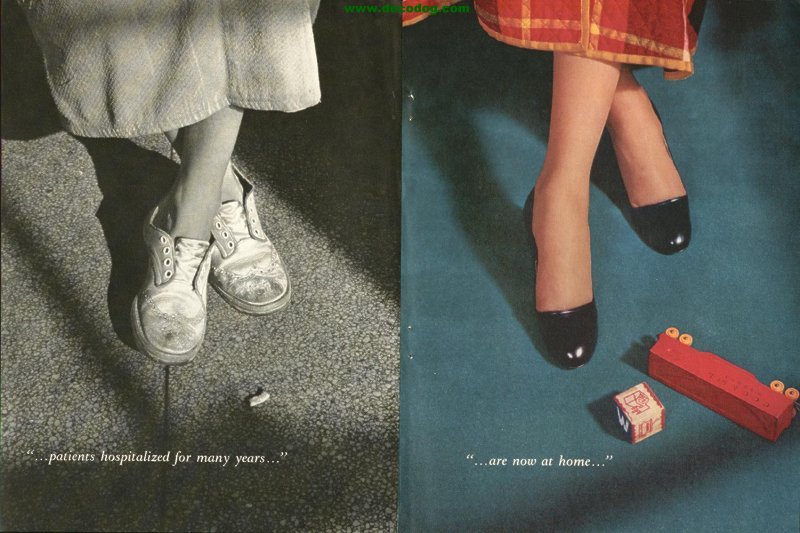

These adds are in sharp contrast to previous marketing campaigns that framed schizophrenia in the 1950s as a mental condition affecting mostly middle class patients, and especially women. Also shown below, ideas of schizophrenia were at that time an amorphous collection of psychotic and neurotic symptoms that were thought to afflict many women who struggled to accept the routines of domesticity.

While schizophrenia is certainly a real, frightening, debilitating disease, Metzl reminds us that cultural assumptions of the “other” shape how psychiatry understands and treats the condition.

————————

Arturo Baiocchi is a doctoral student in Minnesota interested in issues of mental health, race, and inequality. He is writing his dissertation on how young adults leaving the foster care system understand their mental health needs. He is also a frequent contributor to various Society Pages podcasts and wanted to post something related to a recent interview he did about the racialization of mental illness.

If you would like to write a post for Sociological Images, please see our Guidelines for Guest Bloggers.