In recent years, as states around the country have been faced with the worst budget deficits on record, funding for many social service programs has been slashed or cut entirely. A new report from the NAACP demonstrates that during these budget clashes, funding for prisons has won out over spending for education. The report argues that these “misplaced priorities” are ultimately destructive. Expanding prisons at this point does little to reduce crime and by spending these limited budget dollars on prisons rather than education, we are condemning the next generation of kids in poor neighborhoods to this same cycle of poor education, high crime rates, and mass incarceration.

However, the NAACP report only describes the first half of the problem—the failures of schools and the expansive role of the criminal justice system. The other half of the story is the legacy of these failures—strikingly low levels of education among those who wind up in our nation’s prisons—and the fact that corrections departments today are doing a worse job than ever in providing education inside of prisons as a way out of the revolving door of corrections.

This is important because we know that over 90 percent of inmates are at some point released and roughly half of them will return to prison within the next 3 years. Slashing prison education funding may provide a very small benefit to the current budget, but it also helps to fuel the growth in prisons that has suffocated education funding in the first place.

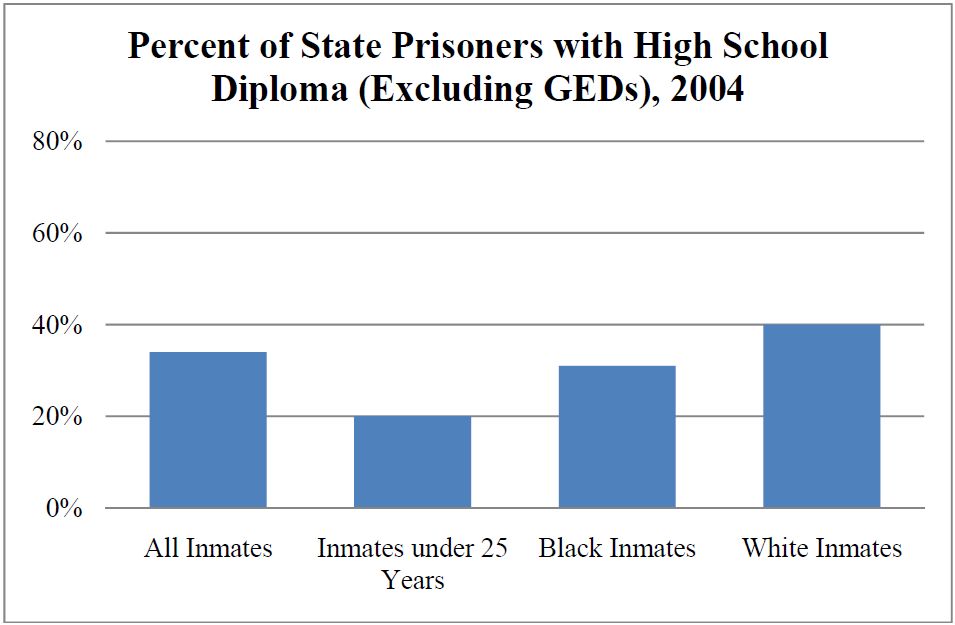

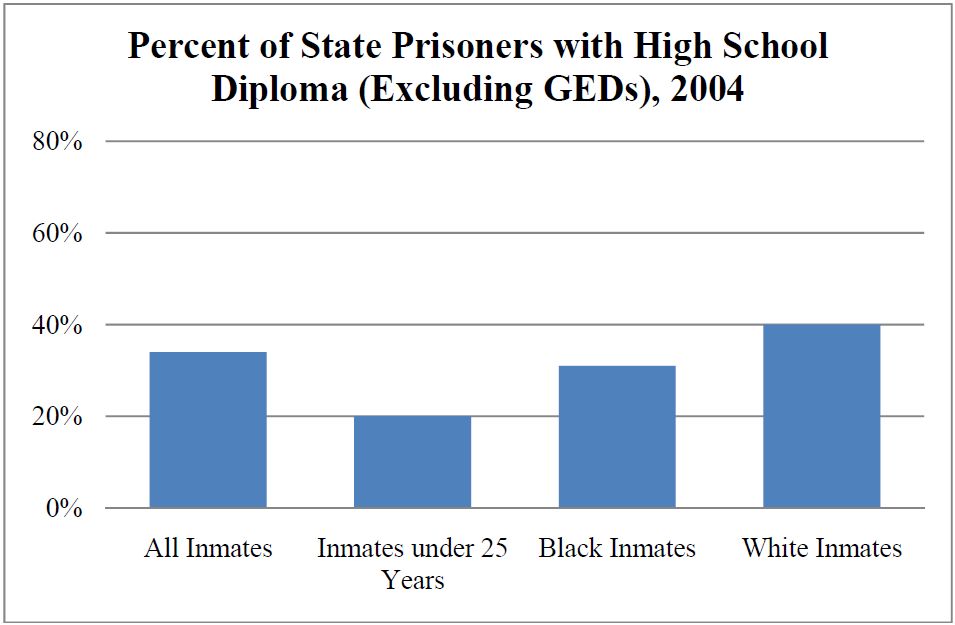

It is simple to document the dire educational needs of prisoners. According to the 2004 Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities, over 60 percent of state inmates never made it past 11th grade in school. Among young inmates under 25 years of age, only 20 percent have completed high school. If G.E.D.’s are included in this measure, only 66 percent of inmates 25 years or older have completed their basic education, compared to 85 percent of adults in the non-institutionalized population.

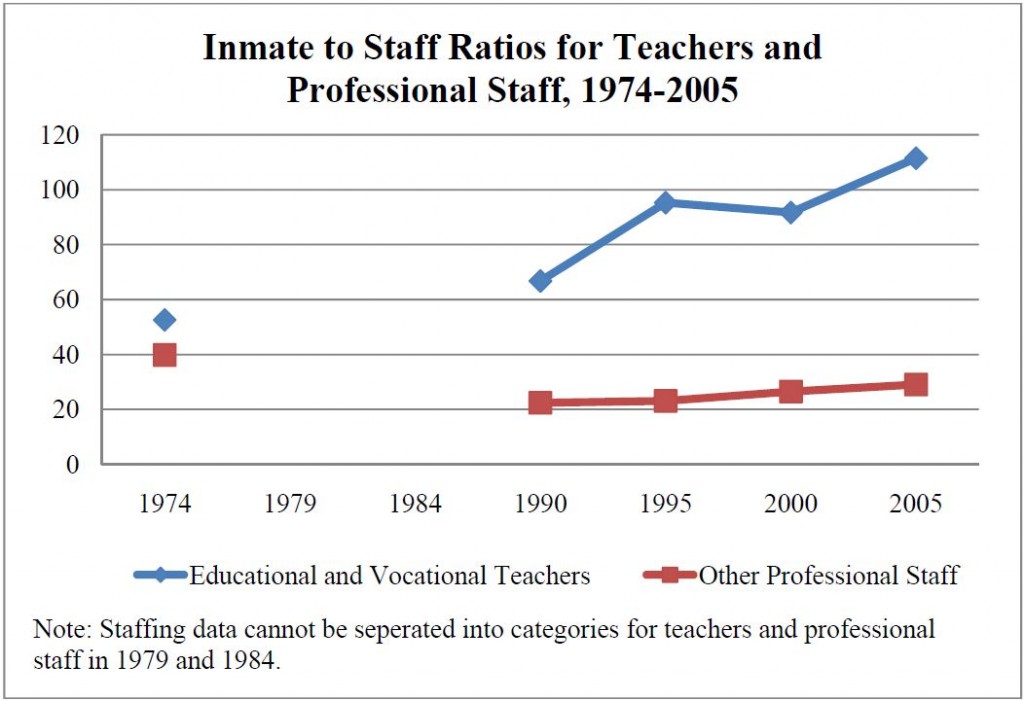

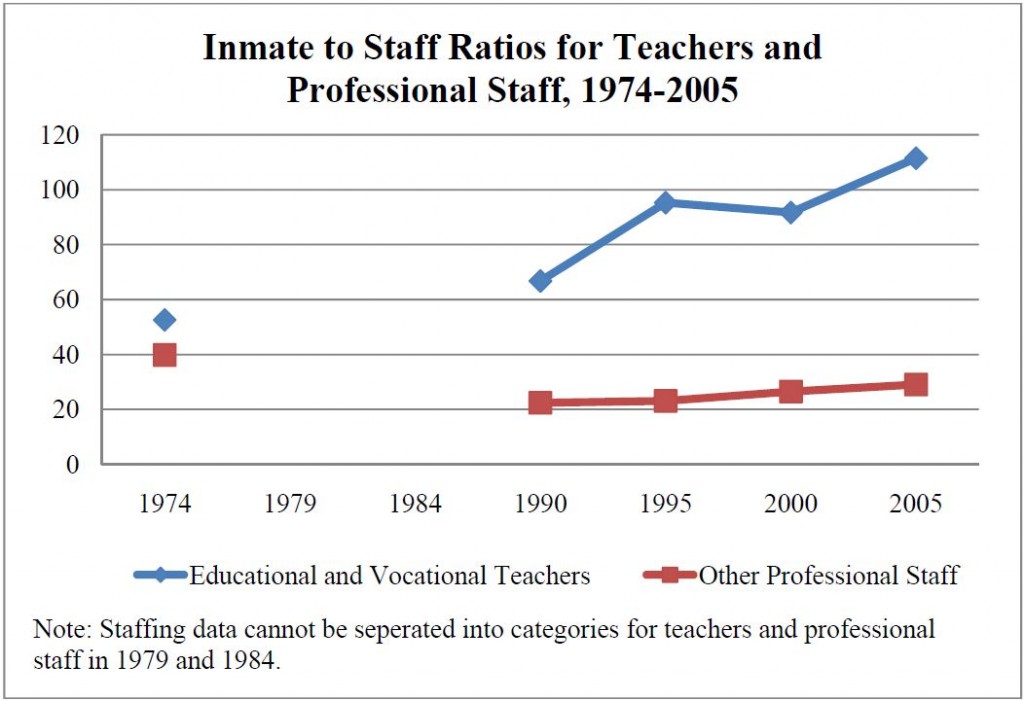

Sadly, the programs that serve these inmates’ needs have been on the chopping block for years. In work recently published in Law & Society Review, I show that the ratio of inmates to teachers for academic and vocational education in prisons nationwide has more than doubled since the 1970s, growing from 53 inmates per teacher in 1974 to 112 inmates per teacher in 2005. Much of this change occurred in the most recent decade: in 1990, the ratio was only 67 inmates per teacher.

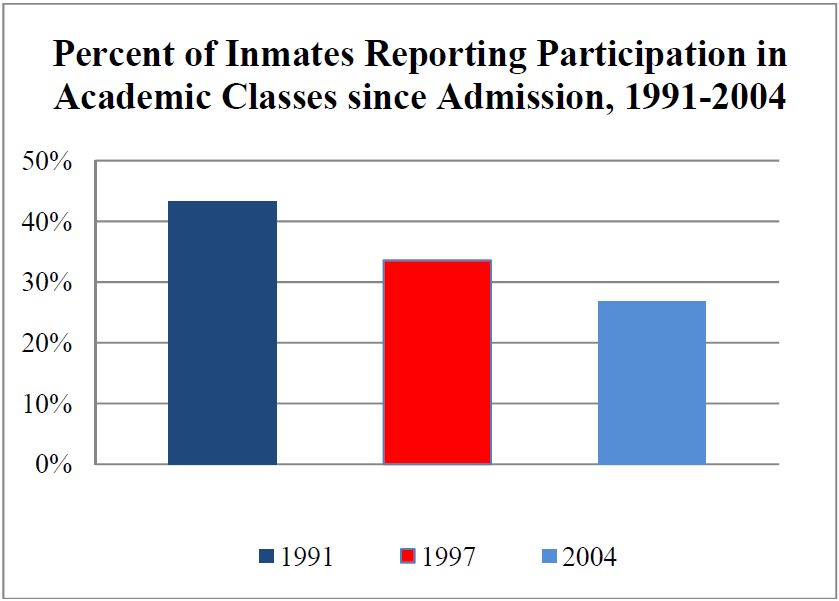

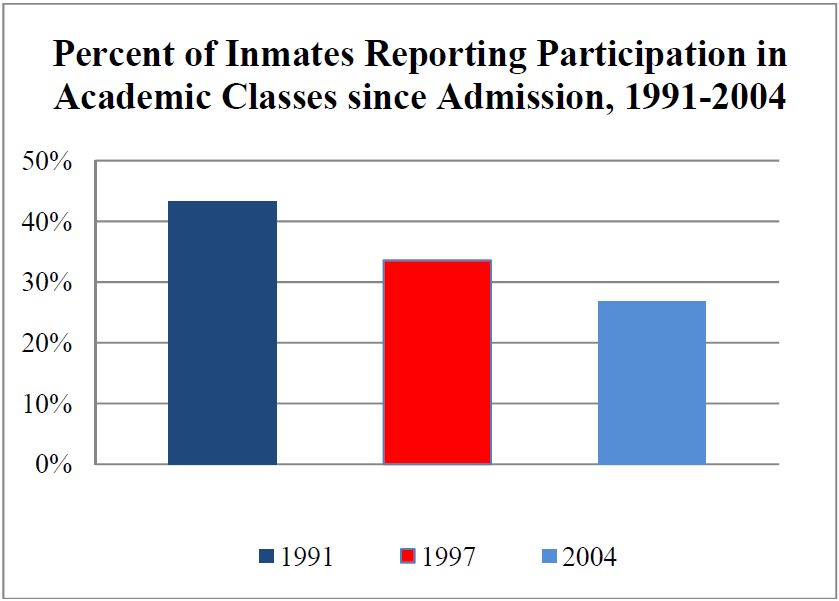

These declines in staffing investments are clearly translating into declining participation in prison education programs. Between 1991 and 2004, the percent of inmates reporting past or current participation in academic classes dropped precipitously from 43 percent to 27 percent. If the rate of high school attendance had dropped by almost 50% in the span of a decade and a half, pundits would be railing against state legislators. But since this happened behind prison walls, there has been very little awareness (let alone outrage) about these changes.

This strategy is a flawed attempt to cut costs since we know that education is one of the more successful ways to reduce recidivism. In study after study, inmates who participate in educational programming are less likely to commit new crimes after release and to be re-incarcerated. This is in part because basic academic education and vocational training makes it more possible for ex-felons to find the kind of employment opportunities that forestall re-incarceration.

In recent years, this disinvestment in prison education has been even more brutal. In California, state lawmakers have taken $250 million away from rehabilitation programs in the last two years and are planning to cut another $150 million in the coming year. These losses in funding translate into a third of the adult programming budget. These cuts are an ironic move after Governor Schwarzenegger’s 2004 decision to change the name of the state agency from the “Department of Corrections” to the “Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation”.

Although some states have begun looking into ways to reduce correctional populations as a more sustainable way to manage costs, in the next few years, we can expect to see even more slashes to prison education funding. Ultimately, this strategy is likely only to cut a small percentage of states’ immediate costs and will increase the need for incarceration spending in the near future.

—————————

Michelle Phelps is a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology and Social Policy at Princeton University. Her work focuses on the punitive turn in the criminal justice system, examining how the daily operations of prisons changed (and remained the same) during the massive recent shift in the rhetoric and politics of punishment. Her dissertation project is on the rise of probation supervision and you can find her new blog on the strange media surrounding probation at Probation Research.

If you would like to write a post for Sociological Images, please see our Guidelines for Guest Bloggers.