Ezra Klein at Wonkblog has put together an impressive collection of statistics on guns and mass shootings, including this data on public opinion on gun control.

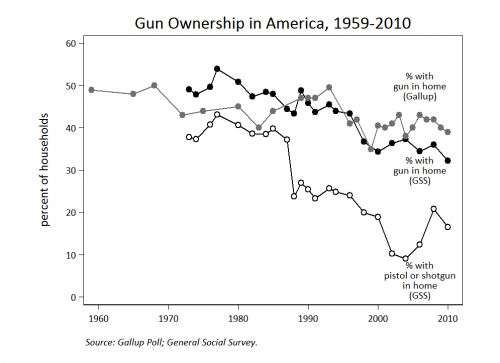

To begin, people seem generally less interested in owning guns. The percent of households with guns has been steadily decreasing for decades:

But, perhaps counter-intuitively, support for gun control has waned:

We might expect a tragedy like this week’s shooting to raise the overall level of support for gun control, but it probably won’t. Previous shootings have not had much of an impact on opinion:

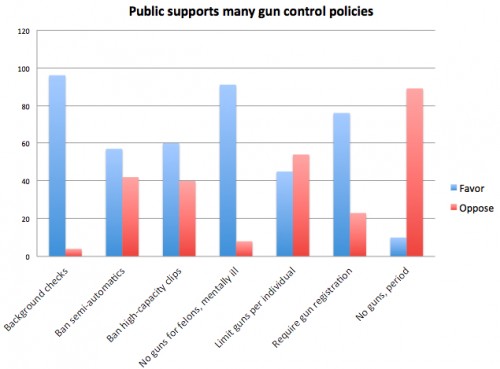

Still, there is more support for some forms of gun control than others:

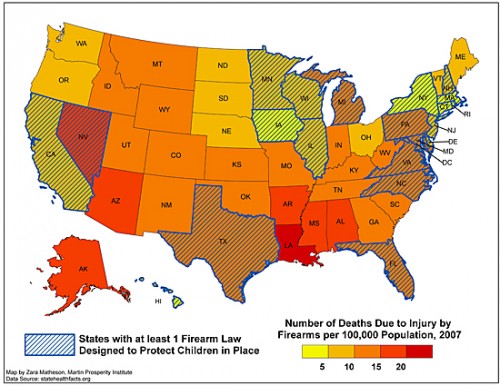

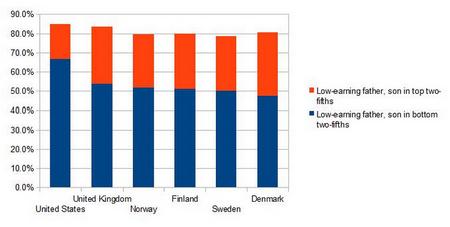

For what it’s worth, gun-related deaths are lower in states with stronger gun control. Economist Richard Florida found “substantial negative correlations between firearm deaths and states that ban assault weapons (-.45), require trigger locks (-.42), and mandate safe storage requirements for guns (-.48)”:

It’s hard to know, however, whether this is correlation or causation. Florida did not find correlations between gun deaths and other factors that we might expect to be correlated, including dense populations, high rates of stress, high numbers of immigrants, and mental illness.

Klein thinks that now is the time to talk about the role of gun control in preventing tragedies like the one in Newtown. He suggests we go ahead and politicize the shooting, since silencing a discussion is just another form of politicization. He writes:

If roads were collapsing all across the United States, killing dozens of drivers, we would surely see that as a moment to talk about what we could do to keep roads from collapsing. If terrorists were detonating bombs in port after port, you can be sure Congress would be working to upgrade the nation’s security measures. If a plague was ripping through communities, public-health officials would be working feverishly to contain it.

Only with gun violence do we respond to repeated tragedies by saying that mourning is acceptable but discussing how to prevent more tragedies is not. “Too soon,” howl supporters of loose gun laws. But as others have observed, talking about how to stop mass shootings in the aftermath of a string of mass shootings isn’t “too soon.” It’s much too late.

I agree that now is a good time to talk about gun control. And, we should do it with as many facts as possible, no matter where they lead us.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.