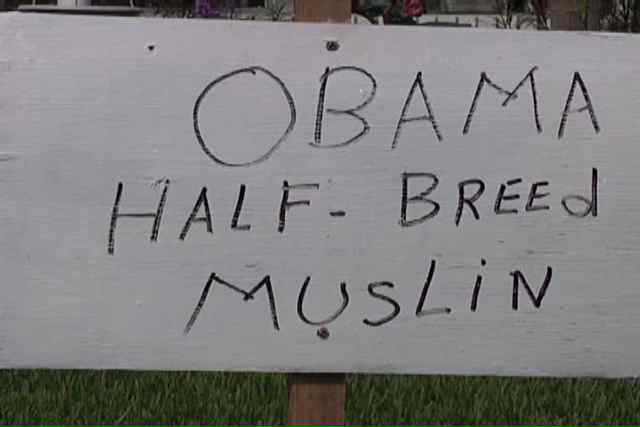

A couple of weeks ago I posted about American Indian sports mascots. An interesting comparison to spark discussion, and an example students often bring up, is the University of Notre Dame’s mascot. The name of the Notre Dame athletic teams is the Fighting Irish, and the official mascot is the leprechaun (image found at Wikipedia):

Each year a student is chosen to be the leprechaun. Here is an image (found here) of the Notre Dame leprechaun performing at a game:

According to the Notre Dame website, the leprechaun did not become the official mascot until 1965; before that, the university was represented by Irish terrier dogs.

You might compare this to the Chief Illini logo, as well as the University of Illinois student performing as Chief Illini, both in the original mascots post. It brings up some interesting issues for discussion. Is there any difference between the the Fighting Irish and the Fighting Illini (or the Fighting Sioux, the Redskins, etc.)? Does the existence of the Fighting Irish invalidate opposition to American Indian mascots? Opponents to Indian mascots often argue that they objectify American Indians in a way that would not be allowed if used against African Americans or Asians–that this modern form of blackface is acceptable only when used to mimic Native American groups or cultural traditions. Those who support American Indian mascots often use the Fighting Irish to try to invalidate that criticism–to argue that Whites are also used as mascots and don’t seem to mind (to my knowledge, there is no movement against the Notre Dame mascot based on the idea that it is offensive to the Irish), and thus that critics of American Indian mascots are over-sensitive whiners.

Opponents of American Indian mascots respond that, first, this is one example, compared to the many, many American Indian mascots found throughout the U.S., and second, whereas Americans of Irish descent face no systematic ethnicity-based discrimination in the U.S. today (and haven’t for several decades), Native Americans still do. In addition, they argue that many American Indian groups openly oppose Indian mascots, and that their voices deserve to be heard; presumably, if Irish-Americans began to protest the Fighting Irish mascot, the same logic would hold and, indeed, those opposing American Indian mascots would oppose the Fighting Irish as well.

This might be useful not just for a discussion of sports mascots, but more generally for a discussion of the idea of equivalency in discrimination. I see this a lot with students–if, for instance, we’re discussing sexual harassment and they can point to an example when a man was sexually harassed by a woman, then they argue that men are affected just like women, and thus it has nothing to do with gender inequality or power. I suspect those who bring up Notre Dame in an effort to invalidate arguments against Indian mascots are doing the same thing–if a White ethnic mascot exists, then charges that Indian mascots are racist can be dismissed. It’s a false form of equalizing because it ignores the lop-sidedness of the “equality” (the tiny number of non-Indian racialized mascots compared to the number of Indian ones) and the role of systemic inequality (that American Indians are underrepresented at colleges and universities and face racial discrimination in a way that Irish-Americans do not). And it also serves to discount opponents’ voices by saying that if any social group wouldn’t be opposed to a particular type of portrayal or treatment, then no one else has any right to be offended by it, either, regardless of their different histories, treatment, or social positions.