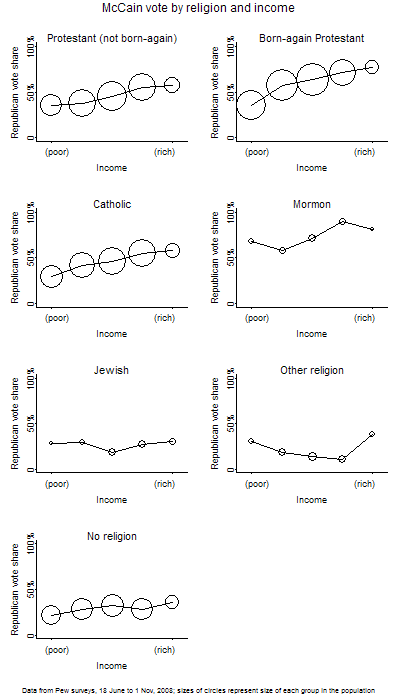

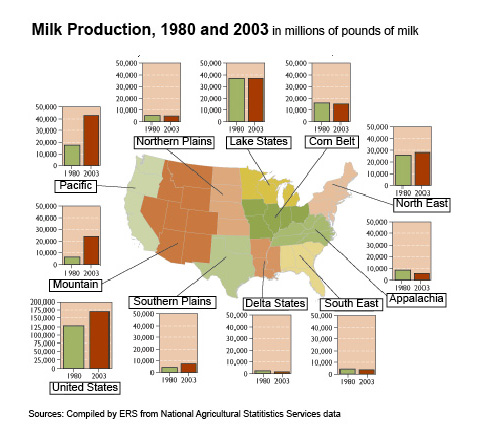

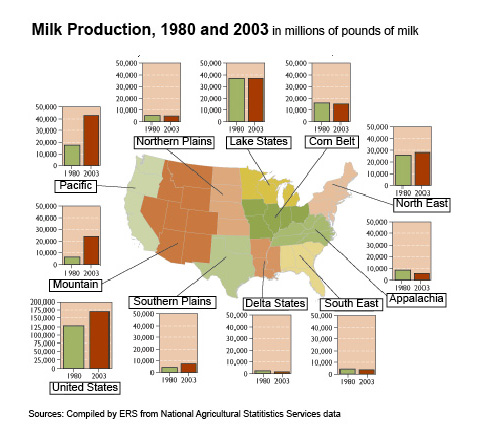

Fellow Contexts blogger Flaneuse over at Graphic Sociology posted this map showing increases in milk production by region:

As we see, overall production has been more or less stable in most regions but has increased dramatically in the Pacific and Mountain regions.

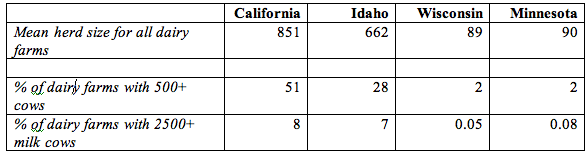

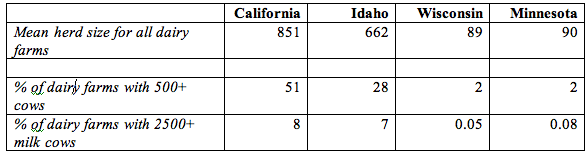

This data hides another pattern, however: changes in average dairy herd size. Dairy operations in the West and Pacific regions tend to be significantly larger than dairy farms in the more traditional dairy states in the Great Lakes region and the Northeast. I went to the 2007 Census of Agriculture site and grabbed some data to do a few quick calculations. I chose two states in the western U.S. and two in the traditional Dairy Belt, just for illustrative purposes:

All calculations use data available in Table 17 in the Census reports for the total U.S. and each individual state, which you can easily access at the link above if you want to check my numbers. I rounded everything off to the next highest whole number except for the two percentages in the lower right-hand cells, where doing so would greatly over-represent the percent of farms of that size.

In general, dairy farms with more than 500 milking cows are considered very large in the industry. Those with over 2500 cows are really extremely large, though there are dairies with more than 10,000 milking cows (including the Vander Eyk dairy, which supplies organic milk to be sold under the Horizon brand, as well as conventional, non-organic milk to other companies). But I digress.

Anyway, clearly we see that farms in California and Idaho (and the other Pacific/Mountain states) are larger, on average, than dairy farms in the traditional dairy states. The increase in milk production in the western U.S. is due predominantly to increases in the number (and herd sizes) of very large industrial dairies.

The growth of these large dairies depends on very cheap rates for water used to irrigate agricultural land. Those dairies have to grow lots of alfalfa and other feed crops to feed so many cows, since they certainly can’t afford enough land to have thousands of cows on pasture. And big dairies produce enormous amounts of manure that have to be carted off somewhere each day, meaning they often have big manure lagoons where they store it (as well as spraying as much as possible on fields). The lagoons are lovely, if you haven’t ever been really close to one, or perhaps nearly fallen into one while conducting research for your thesis. Not that I know anyone who has had such an experience. Point being, the competitive success of large western dairies is dependent on favorable political conditions (such as decisions to keep agricultural water rates lower than other water usage rates), and they have significant environmental consequences when we consider the use of water for irrigation in states that are often relatively arid and potential pollution from manure runoff.

I have some issues with Flaneuse’s implication that the growth of western dairies is a fairly natural result of population growth because milk is a localized commodity. I don’t know that you can really call milk a localized product these days–California milk is for sale in every state, and CA has aggressively marketed the state’s dairy industry with their “Happy cows” campaign. I can also buy milk from dairies in Minnesota here in Vegas, if I look a bit. So while I’m sure population growth has a role, I think it’s important to look at the political factors–particularly environmental laws as they apply to agriculture and local opposition to large dairies–that encourage the growth of huge industrial dairies in some regions more than others.

Also keep in mind, the production of milk when measured in pounds doesn’t just indicate there are more dairies or more dairy cows…it can also be the result of getting more pounds of milk per year per cow through the use of technologies such as bovine growth hormone (rBGH). I’m not up on rates of use of rBGH by region right at the moment, but I do know its use is nearly universal in industrial dairies; if smaller dairies in the midwest are less likely to use rBGH for various reasons (including concerns about customer opposition), that would also have an impact on where milk production is increasing most rapidly.

That was a lot of rambling to have just added one little image to what was in the original post at Graphic Sociology, but soc of ag is my specialty area and I geek out about it sometimes. You have no idea how much I reined myself in to tell you just this much about the dairy industry!

[Note: If you’re really super interested in this and don’t mind reading academic articles, I suggest an article by Jess Gilbert and Raymond Akor (1988) “Increasing Structural Divergence in U.S. Dairying: California and Wisconsin since 1950,” Rural Sociology 53(1): 56-72. They lay out some of the effects of politics, water subsidies, technological change, etc., and how they’ve favored a particular type of dairy system in the West. Also check out the Program on Agricultural Technology Studies at the University of Wisconsin, which has links to lots of easy-to-understand reports about trends in the dairy industry.]