Miriam B. sent in a link to a blog post about a (presumably–I may be totally wrong) homeless woman on public transportation. I didn’t immediately post it because I kept going back and forth about whether it was appropriate. For one thing, it’s a personal blog, not something put out by an artist, ad agency, political group, etc., and with a few exceptions we usually don’t repost things from personal blogs (unless they’re images of things in the public domain, such as a billboard). I was also trying to decide if I wanted to post images of a possibly mentally-ill woman when it might be opening her up for ridicule (which was the point of the original post), even though she’s not clearly visible in any of them. After talking to Lisa about it, I decided to go ahead, but I’m aware some of you may object.

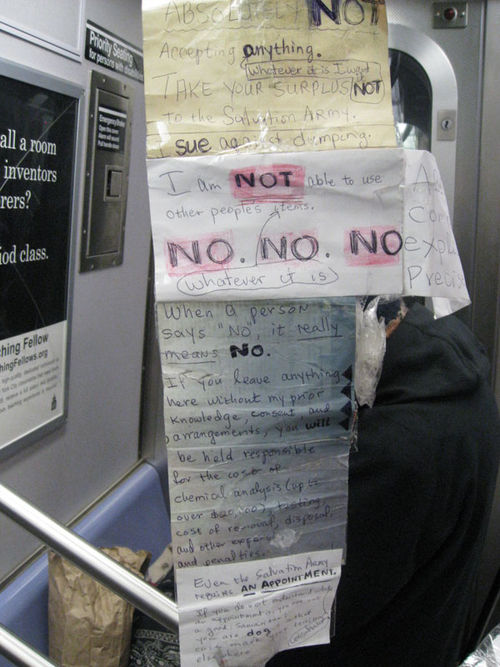

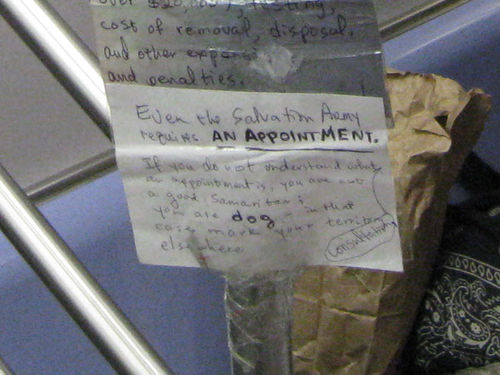

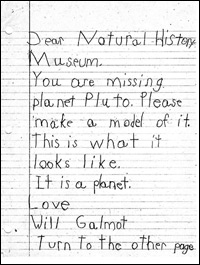

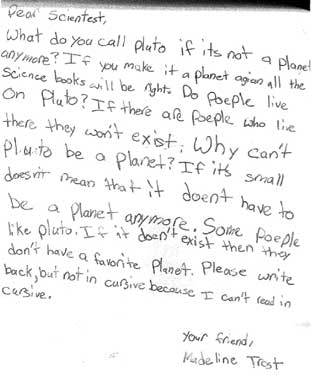

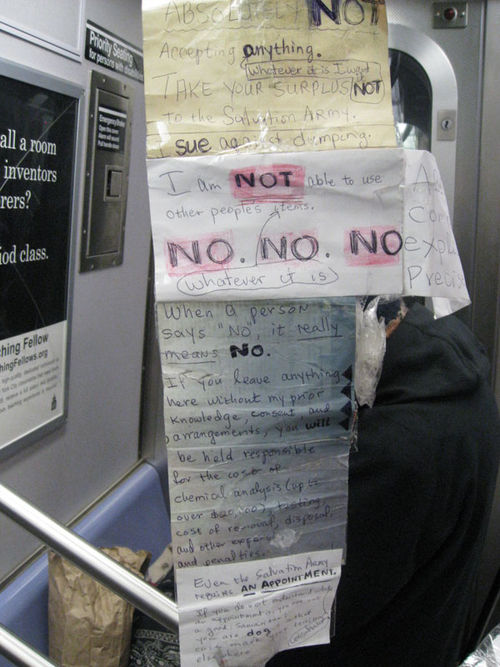

All that said…the point of the original post is that the poster/photographer noticed that the woman has sectioned off a seat on the subway and put up signs, which she clearly spent a lot of time putting together, stating that she didn’t want people’s things:

As Miriam said,

What caused this woman to write such a strongly worded set of rules? What does it imply about how people have treated her in the past? Homeless people have personal boundaries too.

What I found interesting was the tone of the original blog post and the comments to it: basically, a) I can assure that crazy lady, I had no intention of giving her anything in the first place! and b) what an uppity homeless person! What position is she in to say she doesn’t want stuff from strangers?

Of course, the woman might be mentally ill, and that explains her reaction. But it’s also possible that she just does not want people offering her handouts, for whatever reason–maybe sick of them, doesn’t think of herself as a beggar, sense of pride, isn’t homeless, whatever. Or some combination of all of the above. I can see an onlooker finding the vehemence of her statements amusing. But the reaction to her brings up a bigger issue, which seems to be a sense that her insistence that she doesn’t want donations is a sense of “entitlement,” as the original poster called it.

It brings up some interesting questions. Do homeless people lose the right to personal boundaries or to turn down handouts? I think many people will argue the point is the tone of her statements, but I wonder–if a fellow subway passenger offered her a dollar and she kindly said “no, thank you, I’m not a beggar,” would the reaction necessarily be much better? Is part of the problem that she is openly and unapologetically marking off some space on public transit as hers (though not much more space than a lot of people take up with their oversized purses, briefcases, etc.)? Is it that she’s ridiculing the idea of the rest of us as Good Samaritans when we give money or items to the poor?

I might be more sympathetic to her message than most because I’ve worked at a number of non-profits and see some of the weird issues that can arise around donations. People or businesses will sometimes show up with large quantities of products that, while we might be thrilled to have some of them, were difficult to deal with all at once, store, etc. If individuals called and offered things that we couldn’t use, no matter how how politely we explained that we didn’t need or could store the item, the reaction was generally a sense of moral outrage–we were a service agency being offered free stuff! How dare we not immediately say yes, offer to come get it ourselves, and express our gratitude? People seemed to take it very personally if we could not accept a particular donation. [For the record: of course organizations want donations. But if it’s a large amount, oddly sized, etc., you might call ahead and make sure it’s something they have room for. And seriously, don’t use non-profits as an alternative to taking real, true junk to the dump or whatever–they can’t use your permanently-broken washing machine any more than you can.]

I don’t know. Thoughts?

(And yes, it did make me think of the “Seinfeld” episode where Elaine and Kramer are trying to get rid of all the muffin stumps and the woman at the shelter yells at them, saying just because people are homeless doesn’t mean they want their stumps.)