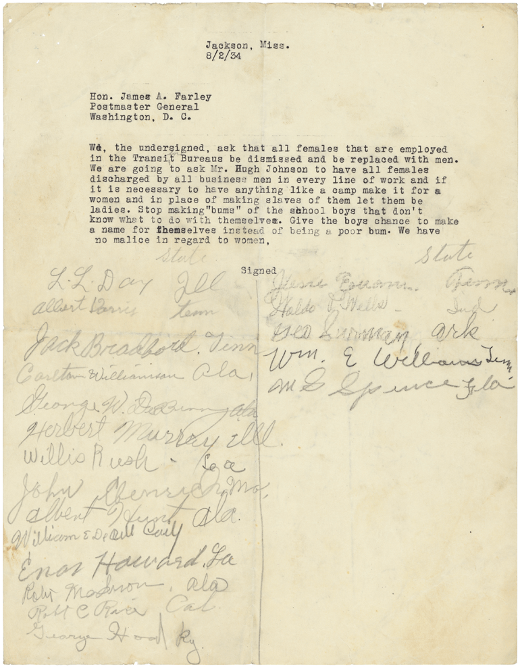

Hermes sent in a link to a feature in The Morning News titled “Men at Their Most Masculine,” in which men were asked about what made them feel masculine and photographed in situations that reflect their masculine identities. Some quotes from men included in the project:

“I feel masculine when I am home, I can take care of myself. I often feel emasculated when I leave my apartment though, with everyone asking me if I need help. I don’t need any help.”

“To be masculine is to dominate in one’s field of study.”

“I want to show that, despite stereotypes, gay men can be masculine too.”

“I feel most masculine when I am lying in bed naked.”

“I am strong emotionally, have always stood up for myself, and fear nothing. I happen to be physically strong but that isn’t where I derive my masculinity.”

“I am masculine because I abandon women after taking their love. Because when you study Freud, you don’t let him study you. Because I study philosophy, not literature.”

Visit at photographer Chad States’s website. He apparently found all of the featured men via craigslist.

The photos and quotes illustrate some interesting contradictions in definitions of masculinity. Several of the men define masculinity in fairly traditional terms, using words like “dominate” or expressing masculinity as the ability to use women and then leave them. There is also an emphasis on being independent and not needing help from anyone else.

In other cases, the men redefine masculinity to at least some extent, such as the gay man who reclaims masculinity for gays, the guy who focuses on being emotionally strong, and the man shown posed in a way we’re more used to seeing with women.

It’s an interesting look at some of the ways men define masculinity at a time when we expect men to be more emotionally available and involved in family life (as opposed to the 1950s emotionally closed-off model) but provide mixed signals by also still judging men harshly if they seem too emotional or don’t meet ideals of what “real” men should be like.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.