In the last few hundred years, dark-skinned peoples have been likened to apes in an effort to dehumanize them and justify their oppression and exploitation. This is familiar to most Americans as something that is done peculiarly to Black people (as examples, see here, here, and here). The history of U.S. discrimination against the Irish, however, offers an interesting comparative data point. The Irish, too, have been compared to apes, suggesting that this comparison is a generalizable tactic of oppression, not one inspired by the color of the skin of Africans.

Irish woman, “Bridget McBruiser,” contrasted with Florence Nightengale:

(source)

(source)

A similar contrasting of the English woman (left) and the Irish woman (right):

(source)

(source)

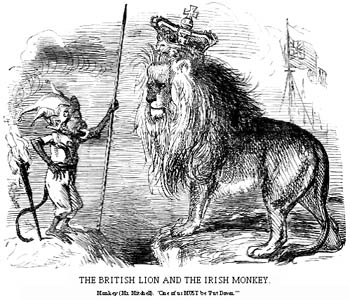

Cartoon facing off “the British Lion” and “the Irish monkey”:

(source)

(source)

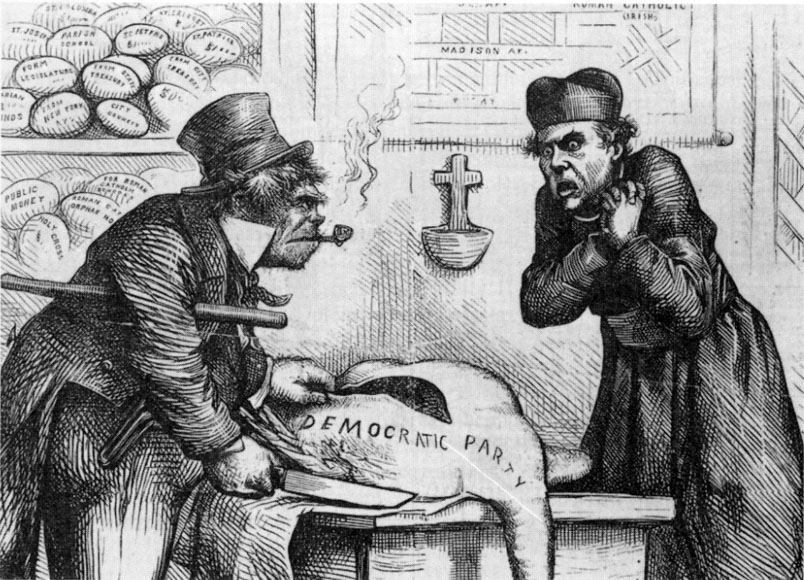

An Irishman, looking decidedly simian, in the left of this cartoon:

(source)

(source)

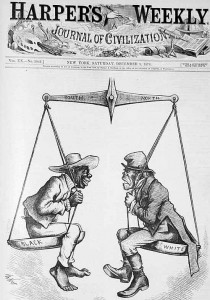

The Irish and the Black are compared as equally problematic to the North and the South respectively. Notice how both are drawn to look less human:

(source)

(source)

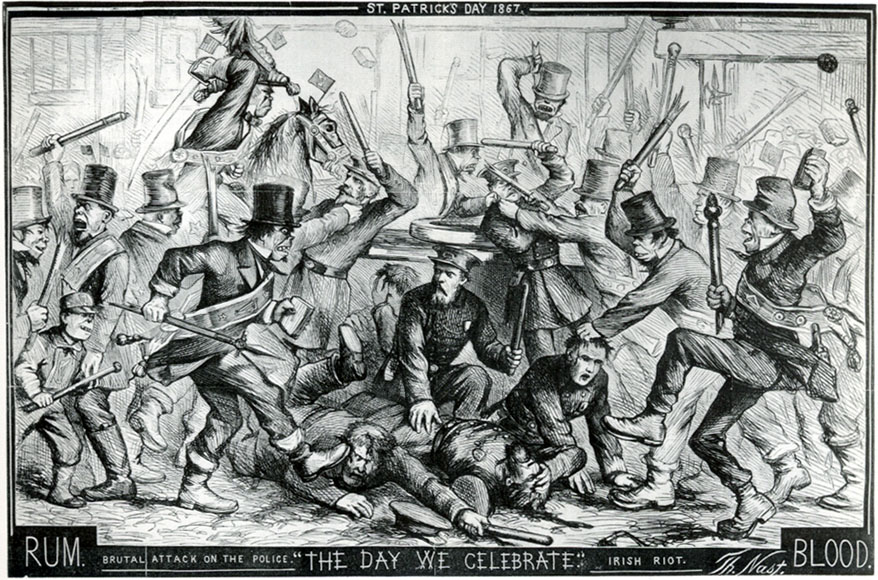

A depiction of an Irish riot (1867):

(source)

(source)

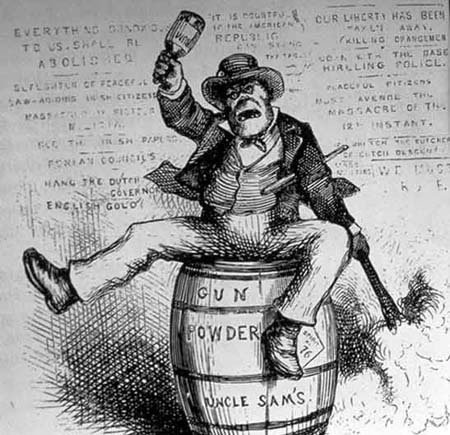

An Irishman, depicted as drunk, sits atop a powderkeg threatening to destroy the U.S.:

(source)

(source)

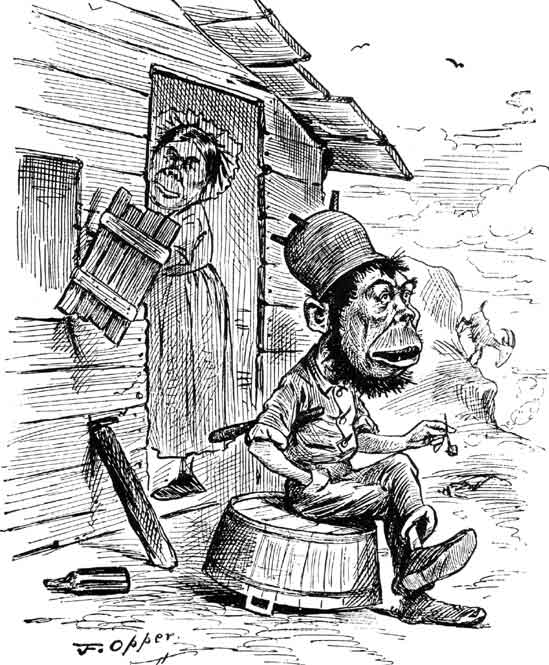

Two similar cartoons from the same source:

About this cartoon, Michael O’Malley at George Mason University writes:

In this cartoon, captioned “A King of -Shanty,” the comparison becomes explicit. The “Ashantee” were a well known African tribe; “shanty” was the Irish word for a shack or poor man’s house. The cartoon mocks Irish poverty, caricatures irish people as ape like and primitive, and suggests they are little different from Africans, who the cartoonists seems to see the same way. This cartroon irishman has, again, the outhrust mouth, sloping forehead, and flat wide nose of the standard Irish caricature.

(source)

(source)

So, there you have it. Being compared to apes is tactic of oppression totally unrelated to skin color — that is, it has nothing to do with Black people and everything to do with the effort to exert control and power.

For more on anti-Irish discrimination, see our post on Gingerism. And see our earlier post on anti-Irish caricaturein which we touched on this before.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.