I couldn’t decide if I was surprised or not when I read that Westboro Baptist Church (WBC) was protesting Kim Davis. WBC is notorious for their protests, and their targets have ranged from U.S. soldiers killed in combat to country western singer, Blake Shelton. Add Kim Davis to a long list. But of course it is peculiar that the “God Hates Fags” church would protest the person who, at least this month, epitomizes religious resistance to gay rights. Dr. Rebecca Barrett Fox, who has studied WBC for more than a decade, generously agreed to answer some questions about this seeming contradiction.

I couldn’t decide if I was surprised or not when I read that Westboro Baptist Church (WBC) was protesting Kim Davis. WBC is notorious for their protests, and their targets have ranged from U.S. soldiers killed in combat to country western singer, Blake Shelton. Add Kim Davis to a long list. But of course it is peculiar that the “God Hates Fags” church would protest the person who, at least this month, epitomizes religious resistance to gay rights. Dr. Rebecca Barrett Fox, who has studied WBC for more than a decade, generously agreed to answer some questions about this seeming contradiction.

Rebecca first encountered Westboro Baptist Church when she accidently stumbled into Fred Phelps’ kitchen where his wife was frying eggs for breakfast. She was a graduate student interested in studying the congregation and arrived on a Sunday morning to find all doors locked except for one to an adjacent building, which happened to be the pastor’s house. That was in 2004 and since then, she has spent countless hours observing church services, conducting interviews, watching pickets, and witnessing arguments at the Supreme Court. A book based on her ethnographic work with the church, God Hates: Wesboro Baptist Church, the Religious Right, and American Nationalism, will be released in 2016 by the University Press of Kansas.

KB: Most readers know about Westboro Baptist Church (WBC) from the media storm they have created by protesting gay people and military funerals. Can you explain the religious ideology that fuels their attitudes about what and why to protest?

RBF: In WBC theology, all people are sinners by their nature; all people are totally depraved and unable to do a single thing to bring them out of sin or closer to God. This includes every member of WBC. The good news is that God has elected some people to love and save and others to punish and damn. And if God has elected you, you cannot resist him, so you will heed his call and turn toward righteousness. That is, you live a godly life, even though you are by nature a sinner, because God has elected you; you don’t get into heaven because you live a godly life. It’s important in this theology not to reverse the cause and effect.

While we can’t know who is going to heaven (since righteous living is only a hint that you might be elect, not a reason for it), we can know who is going to hell—or at least some of them. If you aren’t living a godly life, it’s because God hasn’t elected you; and he hasn’t elected you because he hates you, which is his prerogative as your creator. Remember that the elect can’t resist living a righteous life, so the only people left to dwell in disobedience are the damned, those chosen by God for his holy hatred before they were even born.

While we can’t know who is going to heaven (since righteous living is only a hint that you might be elect, not a reason for it), we can know who is going to hell—or at least some of them. If you aren’t living a godly life, it’s because God hasn’t elected you; and he hasn’t elected you because he hates you, which is his prerogative as your creator. Remember that the elect can’t resist living a righteous life, so the only people left to dwell in disobedience are the damned, those chosen by God for his holy hatred before they were even born.

That theology is not unique to WBC; it’s called hyper-Calvinism, and while it is not popular, it informed a lot of the work of Puritans. We are seeing, more broadly, a neo-Calvinist revival here in the US, with a few churches even using the word “Puritan” in their name again. Even so, WBC’s particular strain of theology seems mean-spirited to most Christians.

What is striking, I think, is though nearly every conservative Christian church condemns Westboro’s pickets and disagree with their theology, they actually end up at the same place: that gay people (and their supporters) are destroying America. For WBC, God doesn’t hate people because they are gay; they are gay because he hates them. This is different from the “love the sinner, hate the sin” theology of other conservative churches, which Cynthia Burack and others have artfully explored, which say that God loves gay people but just hates that they have same-sex relationships. In the end, though, both groups have God casting those people into hell. Does it matter if God sends you to hell because he hates you (the WBC perspective) or because, despite the fact that he loves you, you just won’t stop being gay? I’m not sure that the Religious Right’s “loving” God here is more appealing than the angry God of WBC.

Both WBC and the Religious Right argue that America’s acceptance of gay people is leading to our doom, both in practical terms—like a weakening of important institutions such as the military and marriage—and in spiritual terms, as God grows angry with us for failing to adhere to his moral code. WBC takes this message to scenes of national tragedy, including military funerals as well as scenes of gay pride. The link seems strange to some, but here it is: In 2003, the US Supreme Court, in Lawrence v. Texas, codified acceptance of same-sex intercourse by striking down state anti-sodomy laws. When it did that, according to WBC, the nation became the enemy of God. And, of course, God punishes his enemies through national tragedies and by destroying the military. Thus, every bad thing that happens to us as a country—every mass murder, every oil spill, every economic downturn, every tornado, every military death—is actively ordered by God to punish us for our acceptance of homosexuality.

But why protest at all and why these moments?

Pickets are one way that God can reach the elect. When you hear WBC, you either dismiss them or hear God’s voice. You don’t get saved by WBC preaching or picketing since your election happened before your birth. However, by your response to WBC, you reveal your election or damnation. Additionally, church members have to picket because they see it as something that God demands of them; they need to do it regardless of how it is received. From a sociological perspective, picketing also serves to discipline the group, to create and maintain boundaries between the inside world of the church, where people have hope for election, and the outside world, which is evil, and to invest people in the church. The picket is as much about the picketers’ performance of their faith as it is about the reactions of passersby, which usually reinforce the church’s view of the world as hostile. And they picket tragic moments, in particular, they say, because this is when people are most vulnerable and thus most open to hearing their message. It seldom works to find new members, of course, as few people hear their words as the words of God, but the point is as much to help people see their damnation as their salvation, so every picket is a victory in that sense.

Were you surprised when you learned that WBC was speaking out against Kim Davis? Why focus on the private life of Kim Davis, when her public voice aligns with what seems the most pressing beliefs of WBC? What about forgiveness of sin?

If religion and sex are in the news, WBC usually weighs in. The Davis case is an example, in WBC eyes, of how Christians have failed to prevent the advancement of the gay agenda by failing to adhere to God’s standards about sexuality more broadly. WBC sees homosexuality as the last sin a culture will accept; by the time we decided to legally recognize gay marriage, we’ve already legalized divorce and remarriage, made adultery commonplace, and legalized abortion. Homosexuality is the last stop on a train we should never have boarded, in this line of thinking. And that is not unique to WBC. The Southern Baptist Convention just excluded a church whose pastor questioned the Convention’s willingness to allow pastors to follow their consciences on marriage for divorced people but not gay people. Many church leaders, including Albert Mohler of the SBC, have had to figure out how to defend a long history of marrying divorced people while denying marriage to gay people.

If religion and sex are in the news, WBC usually weighs in. The Davis case is an example, in WBC eyes, of how Christians have failed to prevent the advancement of the gay agenda by failing to adhere to God’s standards about sexuality more broadly. WBC sees homosexuality as the last sin a culture will accept; by the time we decided to legally recognize gay marriage, we’ve already legalized divorce and remarriage, made adultery commonplace, and legalized abortion. Homosexuality is the last stop on a train we should never have boarded, in this line of thinking. And that is not unique to WBC. The Southern Baptist Convention just excluded a church whose pastor questioned the Convention’s willingness to allow pastors to follow their consciences on marriage for divorced people but not gay people. Many church leaders, including Albert Mohler of the SBC, have had to figure out how to defend a long history of marrying divorced people while denying marriage to gay people.

Kim Davis, from WBC’s perspective, can’t fully endorse their message because she is living with a man who is not actually her husband. What Davis should do, according to WBC, is to repent of her three most recent marriages and return to her first husband; if he has remarried or is no longer interested in pursuing a relationship with her, she should remain single. For WBC, divorce is only part of the sin; remarriage is also a sin, and you can’t both live in a state of sin and ask for forgiveness for it—just like you can’t both be sexually active in a same-sex relationship and ask for forgiveness for it, a premise shared by WBC and conservative Christian churches. Many Christians, far beyond those at WBC, are willing to call out non-celibate gay Christians as unrepentant but would never ask a divorced and remarried person to abandon their marriage. WBC sees that as hypocrisy.

Are Kim Davis and WBC two sides of the same coin? Or are they really different factions of fundamentalism?

In the end, they both want to deny gay people rights and respect. The theology behind that matters very little in couples’ and families’ lives, and our democracy should not carve out religious exceptions that allow the denial of rights to individuals.

On the other hand, I find Kim Davis far more threatening to democracy than WBC. She is more powerful, able to immediately shape the lives of people in dramatic ways because of her role as an elected official. She is attractive to the Religious Right, and already conservative pundits are using her case as a litmus test for the Republican presidential nomination.

Kim Davis—and the anti-gay Religious Right more broadly—has a friend and a foil in WBC, in that the church recalibrates the scale of hate to make the Religious Right look more reasonable and tolerant. As long as Westboro Baptist Church is there, the Religious Right can point to them and say, “We’re not like that! We love gay people! We just hate their sinful ways!”

People like Kim Davis and members of WBC are an increasingly marginal group in the contemporary U.S. Should we pay attention to what they say?

Yes, I think we must. These groups are marginal in the sense that they are small and often times reviled. But they do important work for those who oppose hate by revealing, in a community’s response, where it fails to protect those on its own margins. It’s easy to rally against hatred in general; it’s harder for a community to rally against homophobia and even harder to really question its own investments in heteronormativity. It’s easy to organize a counterpicket and drive a small group of people you already see as nutty out of your town, especially when they are really only in town for an hour or two anyway; it’s harder to build coalitions across long-standing prejudices and suspicions held by neighbors. Can communities embrace those challenges? I’m hopeful.

Dr. Rebecca Barrett Fox teaches sociology at Arkansas State University, where she continues her research on religion and hate groups.

Dr. Rebecca Barrett Fox teaches sociology at Arkansas State University, where she continues her research on religion and hate groups.

Reading

Reading

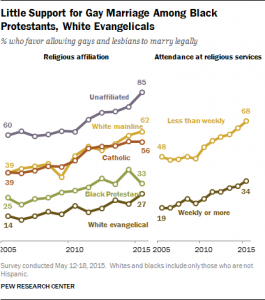

White conservative Protestant evangelicals have been the obligatory homophobes in the political controversy over same-sex marriage in America

White conservative Protestant evangelicals have been the obligatory homophobes in the political controversy over same-sex marriage in America